Lots of cities are trying to prevent gun violence. What’s working? And what lessons can Philly’s next mayor take?

Philly’s newly elected mayor will need to address the gun violence crisis. Can strategies piloted in other cities serve as a guide?

Listen 4:08

Police officers walk in the area of a shooting in Philadelphia, Wednesday, April 6, 2022. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

This story is a part of the Every Voice, Every Vote series.

What questions do you have about the 2023 elections? What major issues do you want candidates to address? Let us know.

Philadelphia’s next mayor needs a gun violence plan.

There were 562 homicides in Philadelphia in 2021 and 516 in 2022, most due to gunfire according to the Office of the Controller’s analysis of Philadelphia Police Department data. The last time the murder tally reached 500 was in 1990, according to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting system. Public safety is already a leading topic for candidates on the campaign trail.

Philly’s situation mirrors what other major cities are seeing — an explosion of violent crime in historically disadvantaged neighborhoods that mostly takes the lives of Black men under 30, according to a Brookings Institution analysis of U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data. Experts say mayoral hopefuls should be crafting a gameplan by looking at what’s failed and succeeded in other major metropolitan areas.

“This is not unique to Philadelphia, but given Philadelphia’s size, as well as the size of the problem, it is uniquely in need of improvement,” said David Muhammad, who heads the National Institute for Criminal Justice Reform and has overseen gun violence reduction plans in Oakland, Indianapolis, and Washington D.C.

“What has worked in several cities is a clear, specific focus on the people who are at the very highest risk of gun violence and an intensive engagement with those individuals,” he said.

Murder rates in major U.S. cities rose 34% in 2020, according to an analysis from New York University’s Brennan Center for Justice, while suburbs and rural areas saw a smaller change. The Northeast and Midwest experienced a 36% increase, while the South and West saw a 26% jump.

The numbers haven’t improved. The latest data from the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention shows homicide rates held steady through the second half of 2022.

The race to replace Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney is a crowded one. Some candidates have leaned heavily into police recruitment, while others are putting more emphasis on improving neighborhoods where shootings are rampant.

Whoever takes the reins will inherit a jumble of gun violence reduction strategies Kenney’s administration has tried over the last four years, most of which are laid out in the 2019 Roadmap to Safer Communities.

The plans include:

- Funding community-based organizations

- Gathering resident feedback through “listening tours”

- Cleaning and greening vacant lots

- Launching a hotspots policing initiative

- Enstating a teen curfew and opening evening resource centers

- Establishing an Office of the Victim Advocate

- Revitalizing recreation centers in high-crime areas

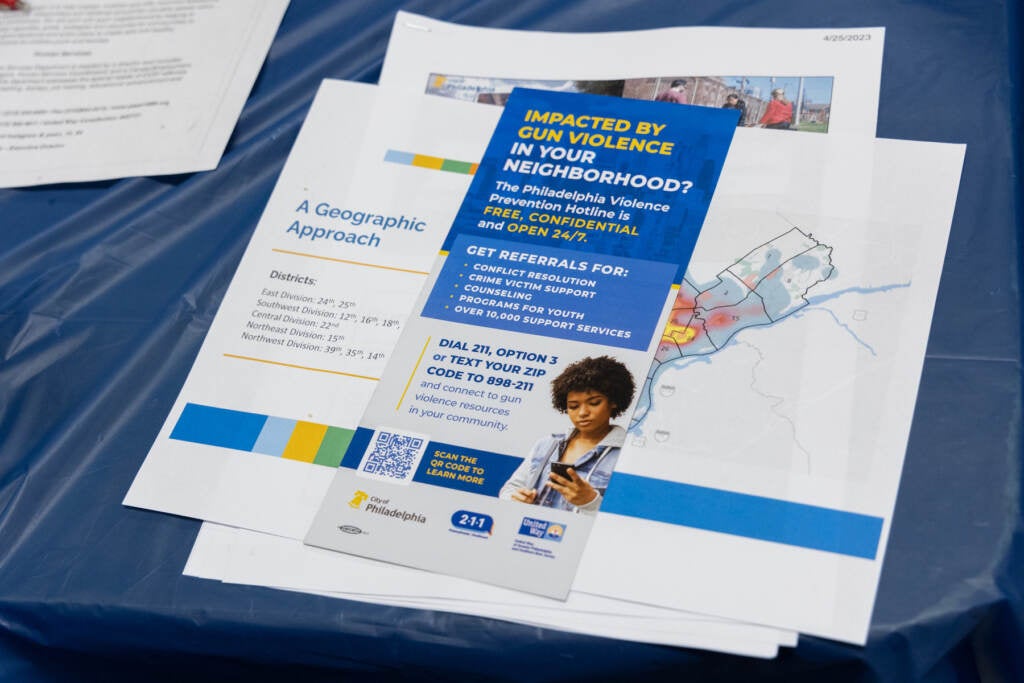

The city allocated $208 million to anti-violence initiatives in 2023 according to the Office of the Controller — out of the total $5.7 billion budget. Roughly 80% of it is generated by local tax revenues, with about $287 million coming from state and federal aid and about $400 million coming from “other funds,” including the American Rescue Plan, according to budget documents.

Philadelphia invested about $54 million more than it did in 2022 — though a budget analysis from the Office of the Controller found only 17% of that money supports interventions that address violence in the short-term. Just under three-quarters of it goes to preventive or transformational programs that reduce violence in five to 20 years, and the rest goes to policing initiatives. A full breakdown of that spending is available online.

Philadelphia leaders are already looking to other cities for help. Recently, they’ve been gearing up to launch a pilot program focused on workplace readiness originally slated for summer 2021, according to a city report. That program is modeled off of a similar initiative in Chicago.

“Next fiscal year we will expand our violence prevention programs, improve the quality of life in Philadelphia and make sure every neighborhood has safe streets,” said city managing director Tumar Alexander at a recent budget hearing. “Residents continue to confront the trauma of gun violence. Understanding the magnitude of these issues, we stand committed to resolving them.”

Pastor Carl Day, a long-time Philadelphia gun violence activist who serves on the city’s public-safety-focused Reconciliation Steering Committee, said part of the city’s failure to bring down homicide rates is that leaders are looking outward instead of paying attention to what’s happening on the streets.

“They’re crying for models that worked in other cities, that allegedly worked in other contexts, that worked before the pandemic, but don’t think about how everything has evolved,” he said, noting that people committing shootings became harder to locate during the past two years.

One of the biggest reasons Philadelphia hasn’t seen major success with its gun violence reduction efforts is a lack of coordination between law enforcement, prosecutors, city officials, nonprofit leaders, and residents, said Muhammad, of the National Institute for Criminal Justice Reform.

“You’re talking hundreds of folks who are working incredibly hard every day,” he said. “What if they were in a meeting every single week and coordinating their efforts together, and somebody was in charge of managing that process? … Strong, tight management. Philadelphia has the pieces now, it just needs to bring it all together.”

In Camden, New Jersey — which saw a 58% decrease in shooting homicides between 2012 and 2022 according to Camden County Police Department data — police chief Gabriel Rodriguez says weekly meetings are a staple strategy for locating shooting suspects.

“Those are the folks that are out there terrorizing our neighborhoods, pulling the trigger, and harming folks in a reckless manner,” he said. “Everyone comes together, egos aside, and we work for one common goal and it’s to make our streets safer. And that’s exactly what we are accomplishing.”

The city of Philadelphia does hold weekly tactical meetings with public safety staffers, police captains, license and inspection employees, and local community groups to discuss how to support specific neighborhoods.

“These supports can include lot cleanup, adjustments to PPD patrols, development of a local Town Watch through Town Watch Integrated Services (TWIS), or social service connection,” a city spokesperson wrote in an email. “Through this diverse array of meetings and programs, the City coordinates its violence prevention efforts.”

The spokesperson clarified that the district attorney’s office “has been invited in the past” and “is always invited to relevant community meetings or other gun-violence related events.”

Philadelphia’s gun violence strategies are still young — major programs such as group violence intervention and community expansion grants have been around for fewer than three years.

DeVone Boggan, who founded the Advance Peace street outreach initiative in Richmond, California and has replicated it in other cities such as Sacramento and Stockton, said successful gun violence reduction strategies require a long-term commitment — and leadership turnover can be a detriment.

“You have new members coming into the council all the time, new mayors,” he said. “When you try a strategy today, it doesn’t work in two years and you say, ‘We’ve got to do something else.’ Then you’re going down a rabbit hole and you’ll continue down that sort of spiral.”

WHYY News compiled the following list of gun violence reduction strategies from the National Institute for Criminal Justice Reform, the Vera Institute of Justice, the Council on Criminal Justice and John Jay College of Criminal Justice, as well as from interviews with activists and law enforcement officials in Washington D.C., Oakland and Richmond, California, and Camden, New Jersey.

Identifying at-risk individuals

How it works

Often called focused deterrence or Group Violence Intervention, this strategy involves thoroughly reviewing recent shootings to identify victim and suspect demographics and involvement in prior acts of violence. At group meetings, known as “call-ins,” community members (including formerly incarcerated individuals), law enforcement, violence survivors, and service providers meet with high-risk individuals about how to avoid further conflict, and warn them of criminal justice consequences if they don’t stay on track. These individuals get connected to a life coach — someone with lived experience that mirrors theirs — who works with them for six to 18 months.

Group violence intervention programs differ from street outreach programs because they are more targeted and involve representatives from the criminal justice system.

Case study

Oakland launched its Ceasefire initiative in 2012, at a time when its homicide rates were almost seven times higher than the national rate, according to a Northeastern University study of the program. Researchers found that Ceasefire was associated with a 31.5% reduction in gun homicides between 2010 and 2017, after controlling for other trends and seasonal variations.

David Muhmmad, of the National Council for Criminal Justice Reform, said group violence intervention is most successful when paired with other strategies including street outreach, and that cities should evaluate their approaches as they go.

“This combination of focused intervention on the folks at highest risk, focused enforcement in a constitutional, procedural, just way … well-coordinated, well managed … all of that culminated in eight consecutive years of declines in gun violence in Oakland,” he said.

In Philly

Philadelphia launched its current version of Group Violence Intervention (GVI) in August 2020. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, the city had to rely on door-to-door “mobile call-ins” rather than typical large-group meetings. To date, the GVI program has engaged with 880 candidates and connected 182 of those candidates to services according to the city’s Office of Violence Prevention.

A February 2023 study from the University of Pennsylvania found that participating neighborhoods that received four or more ”treatments” experienced a 44% reduction in shootings per week. That specifically refers to shootings involving groups of people, according to evaluation author Ruth Moyer.

“The takeaway is that the current implementation of GVI in Philadelphia was effective at reducing group-member-involved firearm violence at the group level and also at the place level,” Moyer said.

In response, the city is hiring 15 additional GVI staff to expand services using a $2 million state grant, according to the investments update.

Criticisms

Opponents of this strategy feel that involving law enforcement in interventions poses a barrier to building trust with potential perpetrators.

Violence interruption

How it works

Violence interruption, sometimes called cure violence or street outreach, relies on people who have lived experience with gun violence — sometimes called interrupters, neighborhood change agents or credible messengers — to build relationships with at-risk individuals and help them address conflict calmly. They serve as caseworkers, helping to connect people to housing, education, employment or mental health support. This work can also happen through hospital-based violence intervention programs, where credible messengers step in to help people who’ve been hospitalized due to gun violence in hopes of preventing retaliation.

Case study

In 2007, the city of Richmond, California founded the Office of Neighborhood Safety, which began recruiting and hiring “neighborhood change agents” to patrol their own communities. These workers gather information about brewing conflicts, and also obtain information from the Richmond Police Department about recent shootings in the area, with the hope of identifying and deterring potential perpetrators. Boggan, the program’s founder, said the strategy differs from Group Violence Intervention because individuals involved in gun violence don’t interact with law enforcement.

“An active firearm offender is not interested in partnering with law enforcement, is not interested in trusting law enforcement,” he said. “It’s hard to build any real relationship with the threat … hard to do that when the first thing is, ‘Hey, we know who you are and we’re going to put everything in law enforcement’s power to lock you up if you do X, Y, and Z again.’”

Boggan’s program, now called Advance Peace, places people the group has identified as most likely to commit shootings or be shot in a “high-touch” fellowship program that involves daily check-ins, cognitive behavioral therapy, travel experiences, life coaching, career guidance, and a monthly stipend. The city of Richmond saw a 55% reduction in homicides after Advance Peace’s implementation, according to a 2019 study in the American Journal of Public Health.

In Philly

The city of Philadelphia’s street outreach strategy, called the Community Crisis Intervention Program, involves hiring credible messengers to conduct conflict mediation and connect people to resources, sometimes in collaboration with law enforcement. However, an October 2022 evaluation from the American Institutes of Research found that CCIP is failing to achieve key goals such as conducting group mediations, providing support at hospitals, or distributing public messaging about gun violence, in part due to the lack of a program director.

Philadelphia also has a cure violence program, which runs out of Temple University, and explicitly does not include law enforcement. In addition, some community groups run their own violence interrupter programs.

Criticisms

Cure violence has had mixed success in cities across the U.S, according to a report on five cities published in the Annual Review of Public Health. A Johns Hopkins University study of Baltimore’s version showed that only one of four program sites saw a reduction in both homicides and nonfatal shootings, while a Michigan State University study of Pittsburgh’s program found no significant association between the program and the city’s homicide rate.

Community policing

How it works

Police departments place more officers in high-crime areas, often on foot or on bicycle, and train them to build relationships with community members. Advocates of this strategy say it can help reestablish trust in law enforcement and lead to higher solve rates for murders, consequently reducing gun violence overall.

Case study

Camden, New Jersey disbanded its city police force and had all employees reapply to a countywide force with stricter application guidelines and new physical and psychological tests, according to a 2020 essay from former Camden police chief Scott Thomson. The move was a response to Camden’s high murder rates at the time, and an attempt to address distrust that had long existed between officers and residents.

Camden saw a 58% decrease in shooting homicides between 2012 and 2022, according to the Camden County Police Department. The department’s solve rate for murders also increased from 16% to 61%, according to Camden police chief Gabriel Rodriguez.

Rodriguez said officers are encouraged to hold community events and go door-to-door so they become familiar faces in the neighborhoods they patrol. That goes as far as helping seniors with landscaping.

“We’re getting ready to get busy, we have our own lawn mower with some nice police lights on it,” he said. “We’re cutting their grass, you know, we’re taking them cases of water. We’re doing bingo nights.”

The trust-building occurs alongside efforts to stop low-level crimes such as vehicle abandonment and illegal dumping, which Rodriguez said makes a neighborhood less prone to gun violence. Camden also installed cameras all over the city, and invested in additional technology including Shotspotter, a gunshot audio detection sensor.

He said the combination of these changes has helped their small city thrive.

“When we’re seeing more kids outside riding bikes, we’re seeing people out cleaning the front of their porch or their steps, these are things you never saw before,” he said. “Everyone used to be prisoners of their homes.”

In Philly

The Philadelphia Police Department deploys a community relations team to every police district, according to the department, and says a full community relations plan is forthcoming. However, only 2,500 of the department’s 6,000 officers are assigned to patrol, according to a 2022 audit from the Office of the Controller, and high-violence areas such as Kensington are seeing larger declines in deployment than more tourist-friendly areas such as Center City.

Criticisms

Opponents of community policing feel that law enforcement’s historic mistreatment of Black communities makes trust-building impossible, and argue for law enforcement funding to be funneled toward social services instead.

Ella Lathan contributed to reporting.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to include more recent metrics about Philadelphia’s Group Violence Intervention program.

This story is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Lead support is provided by the William Penn Foundation with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute, Peter and Judy Leone, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Harriet and Larry Weiss, and the Wyncote Foundation, among others. Learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters here.

This story is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Lead support is provided by the William Penn Foundation with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute, Peter and Judy Leone, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Harriet and Larry Weiss, and the Wyncote Foundation, among others. Learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters here.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.