How drinking in bars fueled American independence

A Man Full of Trouble is Philadelphia’s last remaining example of colonial bar culture that birthed the American Revolution.

A Man Full of Trouble historic tavern in Philadelphia is reopened at Second and Spruce streets. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

During Benjamin Franklin’s brief stay in London as a young man, he watched his fellow laborers at a printing shop drink beer with every meal, making them slow to their work and draining their pay.

“I thought it a detestable custom,” Franklin tut-tutted in his autobiography. “I drank only water.”

But earlier, as a teenager in Boston under the feminine pseudonym Silence Dogood, Franklin observed that “moderate” drinking improves the “diffusion of knowledge.”

“‘Tis true, drinking does not improve our faculties, but it enables us to use them,” Franklin wrote in a letter published in his brother’s newspaper, The New-England Courant.

“Much study and experience, and a little liquor, are of absolute necessity for some tempers in order to make them accomplished orators,” he wrote.

The ability of beer and wine to bring people together and hear each other talk became a crucial element for mobilizing the public into the American Revolution.

In 1776, there were more than 120 taverns, inns and “ordinaries” in Philadelphia, not counting illegal serving houses. With an estimated population between 30,000 and 40,000 people, that amounts to an enormous number of bars per capita.

“They are incredibly important,” said Tyler Putman, the manager of gallery interpretation at the Museum of the American Revolution.

“This is the restaurant, the bar, the meeting house,” he said. “If you want to read the latest newspapers, if you want to hear the local gossip and drama, if you want to socialize with people like you or run into total strangers, the place you did that in Philadelphia was in taverns like this.”

Putman was sitting in Philadelphia’s only remaining colonial-era bar, A Man Full of Trouble at Spruce and Second streets, where a commercial wharf once operated in the 18th century.

A Man Full of Trouble first opened in 1759 and served beer and cider through the Revolutionary War. Since then, the building has been used for a variety of things, including a boarding house, a produce stand and a sandwich shop. Most recently, it was owned by the University of Pennsylvania.

In 2021, attorney and real estate investor Dan Wheeler bought the building in a somewhat dilapidated state.

“Like a lot of people, I’ve been walking by it for 30 years and saying, ‘God, would somebody do something with that building?’” he said. “I thought the National Park Service owned it. I didn’t realize it was a thing one could buy.”

Wheeler restored the building as an 18th-century tavern and reopened it last December.

A Man Full of Trouble was not a particularly important tavern in its day, but it has outlived all others in Philadelphia. City Tavern at Walnut and Second streets, where the Founding Fathers were known to imbibe after marathon sessions hashing out the Constitution, burned in 1834 and was later razed. A replica was built in 1976 for the Bicentennial, but even that has been closed since 2020.

The London Coffee House, which was the place to see and be seen for business and politics during the colonial era, used to be on Market Street, once known as High Street. The influential Indian King tavern was also a popular spot run by John Biddle on Bodine Street, an alley off Market Street where a beer garden now operates.

When the Continental Congress voted in 1775 to form a naval force, the basis of what is now the Marines, it recruited its first sailors at the Tun Tavern, located at Sansom Street and what is now roughly the northbound lanes of I-95.

When Benjamin Franklin first arrived in Philadelphia as a 17-year-old runaway from Boston with little money and no place to stay, he had his first meal at the Crooked Billet, a waterfront tavern on the Delaware River. The banks of the Delaware have moved considerably over the last 300 years, so the actual location of the Crooked Billet is, again, likely somewhere underneath I-95.

As America celebrates the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence in 2026, it is worth remembering that Thomas Jefferson composed the famous document with notations directing how it should be dramatically read out loud in public spaces, like taverns.

Also keep in mind that the declaration was originally written by the hand of a brewer. Timothy Matlack sold bottled beer on 4th Street near Market — which Matlack advertised as “remarkably pale, and very good” — and was gifted with penmanship. He laid out and scripted the Declaration on parchment that would be signed by 56 people.

In his book “Colonial Taverns of New Jersey” (2023), author Michael Gabriele wrote that villages were required by law to have a tavern, in order to maintain economic and social stability.

The trip from New York to Philadelphia could take up to three days, depending on weather. If the colonies wanted to foster trade between themselves, travelers needed places to stay. Gabrielle wrote that the Court of Middlesex County decided that “each town was obliged by law as early as 1668 to keep an ordinary or tavern for the relief and entertainment of strangers.”

Gabrielle also cites the Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly, in which attorney Baylen J. Linnekin wrote that taverns offered the “perfect” elements for civic debate.

“Taverns were the only colonial space outside the home that permitted participants in all social classes the opportunity to decide whether, how, and to what extent they would participate and shape their interactions with other,” the article reads.

A Man Full of Trouble is located at what used to be a commercial wharf — the river’s edge has since moved eastward considerably — and was likely where working class dockworkers and lower class indentured servants likely drank. Immediately to the west were some of the wealthiest urban mansions of colonial Philadelphia.

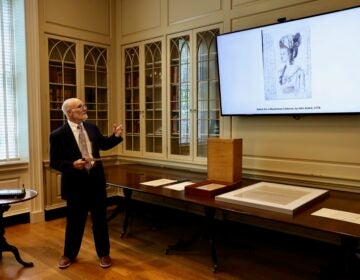

Wheeler, who has assembled a gallery of artifacts on the second floor, said a wide range of social classes likely found their way into Trouble.

“I can show you a map upstairs of Philadelphia in 1776. Basically, we’re right in the center of it,” he said. “It only goes to about 7th Street. It’s a very small town. It’s probably the biggest colonial city, but it was pretty small. Everybody was packed in down here.”

A Man Full of Trouble is just five blocks away from Independence Hall, where the architecture of American democracy was hammered out by the Founding Fathers in sometimes deeply philosophical debates about republicanism and self-rule.

While those discussions may have been too erudite for banter at the local tavern, Putman said the popular spirit of American democracy was seeded in bars.

“If you’re George Washington, you know exactly what the greatest elements of equality are. You’ve got plenty of money. You’ve got property,” he said. “But if you’re drinking in a bar like this and you’re an enslaved person or an indentured servant or a sailor, you have a really personal sense of inequality. That gives you a much better idea of the possibility of change and why you might be enthusiastic about it.”

The Museum of the American Revolution has an artifact that shows how lower-class Philadelphians drinking in taverns may have been invested in the American democratic experiment.

When construction of the museum at 3rd and Chestnut streets began in 2014, the excavation unearthed remains of an illegal bar that operated during the Revolutionary War. The historic record shows that Mary Humphrey lived in the footprint of what is now the museum, and was arrested for serving alcohol without a license.

Among the Humphrey artifacts are pieces of a window pane into which patrons would scratch their names, like graffiti. One of her under-the-radar customers etched the phrase “We admire riches and are in love with idleness.”

The phrase comes from the ancient Roman senator Cato, who excoriated his fellow senators for their corruption and lackluster morals. The writings of Cato had a revival during the American Revolution, which saw the movement adopt his criticism of Caesar and redirect it toward King George and the perceived injustices of British parliament.

The phrase was likely familiar to most Philadelphians in 1776.

“There’s two potential ways that you can interpret it,” Putman said. “One is as a critique of opulent British society. Someone reflecting in America on how Parliament and the British government have become corrupt, how their fellow citizens are in love with idleness and riches.”

“Another way is maybe that it’s just simple bar graffiti,” he said. “This is the sort of thing you could see written in a Philadelphia bathroom in 2025: ‘We admire riches and are in love with idleness.’”

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.