Three years after George Floyd, activists push for racial equity and police accountability

Activists say the energy and purpose of the George Floyd protests continue to fuel social justice fights three years later.

Listen 4:37

Demonstrators took over the Benjamin Franklin Parkway demanding an end to police brutality and justice for George Floyd on June 6, 2020. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Keyssh Datts can’t remember the exact number of days they spent protesting following George Floyd’s murder, but the memories of smoke, tear gas, and the need to flee from encroaching Philadelphia police are vividly imprinted in their mind.

“It was almost like the police was bombing the city,” Datts said. “It was like an explosion.”

Like many other major American cities, Philadelphia saw weeks of citywide marches and demonstrations against police brutality in May and June 2020. On multiple occasions, Philadelphia Police Department officers dispersed crowds with tear gas, rubber bullets, and batons.

Datts was 18 then, and just finishing high school at the time. Datts wasn’t deterred by the intensity of the protests.

“To fight for human rights is really put yourself at risk,” said Datts, now 21 and founder of an organization called Decolonize Philly. “Don’t let fear stop you from fighting for what you know is right, what is the truth.”

The George Floyd demonstrations in Philadelphia pulled together longtime social justice organizers and newly-enraged citizens to rally against Philadelphia’s most powerful institutions. It was a turning point for the city, said activist Samantha Rise, and the energy of it continues to fuel social justice fights three years later.

“You could feel the boiling over as the summer kind of shifted … the relentless violence against the building heat, against the tension and the friction and the pain of decades of unanswered calls for equity and for care and for dignity,” Rise said. “It broke something. And I think the breaking drew all of us toward each other.”

Roughly five months after George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis, police officers in Philadelphia shot and killed Walter Wallace, a 27-year-old with a history of mental illness who was wielding a knife. Residents once again took to the streets in protest. According to activists, 2020 marked the culmination of a series of police killings of unarmed Black Americans – including Breonna Taylor, Stephon Clark, Michael Brown, and many others.

“It’s hard to heal when it doesn’t stop,” Rise said. “It’s been an awful day for three years now.”

Activists say the movement encompasses more than just police brutality now– it’s about racial and economic equity, from efforts to protect an affordable housing complex in University City to the push against a new arena slated for Chinatown.

“The goal is liberation and justice for our people and our communities, and for people who don’t have a voice,” said Asa Khalif, who led demonstrations in 2020. “The poor, low-income people, immigrants, LGBTQ people, Black and brown people, the homeless.”

Police reforms: Where are they now?

In November 2020 voters approved the creation of a new Citizens Police Oversight Commission. The independent group replaced the Police Advisory Commission, which had a smaller budget and less authority.

But the new group is facing internal problems, with a vice chair and two commissioners resigning this week.

In a resignation letter, the commission’s vice-chair said the group is “dysfunctional, toxic, and unable to function as needed.” The interim executive director told Billy Penn that they will now begin the lengthy process of selecting three new commissioners.

On paper, the group is “a Ferrari in terms of its police oversight legislation,” said Adam Geer, deputy inspector general for public safety with the city of Philadelphia’s Inspector General’s Office.

“It’s just sitting in the garage right now apparently,” he said. “Philadelphians deserve for these issues to be resolved as quickly and professionally as possible and to get this thing on the road.”

The commission is tasked with arranging mediation conversations between people who file complaints against police officers and the officers they’re filing against, launching their own investigations into complaints, and reviewing police department policies and procedures.

A ballot measure that would have given the commission increased hiring flexibility failed in the May primary election.

“What’s important now is that there’s more progress made on standing up the CPOC,” Geer said.

Fewer than 1% of all citizen complaints filed against the Philadelphia Police Department between 2015 and 2020 resulted in an officer being formally disciplined, according to a 2021 report from the now-defunct Police Advisory Commission. This is partly due to limitations imposed by Act 111, a state law that creates a process by which officers may appeal a disciplinary ruling to an outside panel.

“Perhaps more officers who are deserving of discipline are getting more discipline,” Geer said. “But then what’s after that? Are they coming back on the force? What does that look like? Because ultimately … in every organization there are going to be some bad apples. And it’s better for everyone if they’re not there.”

Activists say there must be independent oversight to make sure officers are held accountable.

“We can’t afford to coddle and hide and be afraid to call police officers out. If citizens can be arrested and charged with murder, so can police officers,” said Khalif, whose cousin Brandon Tate-Brown was shot and killed by police in 2014. Seth Williams, who served as district attorney at the time, did not file charges.

George Floyd’s murder led to changes designed to prevent interactions between officers and civilians from escalating to violence, such as a ban on no-knock warrant entries and a ban on officers sitting or kneeling on a person’s neck, face, or head.

Police Commissioner Danielle Outlaw said she’s committed to training officers to prevent excessive use-of-force incidents, and holding officers accountable when necessary.

“We’re all just one critical incident away from something,” she said. “The important thing is to ensure that there are structures in place.”

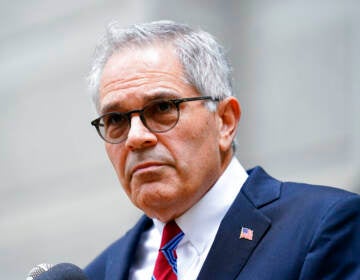

In March 2022, a PPD officer fatally shot a 12-year-old boy. District Attorney Larry Krasner said this case marked the first time an on-duty officer faced first-degree murder charges in Philadelphia, according to 6abc. Earlier this month two officers fatally shot a North Philadelphia man during a foot chase, as reported by 6abc.

Following Floyd’s death, PPD implemented the Active Bystandership for Law Enforcement Program to teach officers how to de-escalate crisis situations. They’ve since trained 4,000 personnel on the program, according to the department’s Crime Prevention and Violence Reduction Action Plan, released in April of this year.

There’s an emphasis on making sure officers report excessive use of force immediately, said Inspector Fran Healy, special advisor to the commissioner.

“They’re human beings, sometimes you lose control, and the purpose of other officers is to intervene, to stop bad things from happening,” said Inspector Fran Healy. “Whether intentional or not, the goal is to make sure people don’t get hurt … It’s everyone’s responsibility.”

Addressing how police officers respond to public demonstrations, Inspector Healy said they’ve created a new tiered system for when to deploy certain tactics – for example, officers must use smoke canisters as a first attempt to disperse a crowd. The department now has a ban on all use of tear gas during non-violent demonstrations.

Reflecting on the 2020 actions around George Floyd’s killing, he said officers did what they needed to in response to “an all-out riot”.

“It may have started as a protest in some cases, but it was an outright assault on police officers,” he said. “We were under attack. “

The city saw an uptick in theft, vandalism, and arson the week after Floyd’s death, according to a crime report analysis by 6abc, though city leaders said those actions were instigated by outside agitators and not local activists.

The city later paid $9.25 million to settle a suit from protesters who say they sustained physical and emotional injuries at the hands of police. A 2021 analysis of PPD’s response from the Office of the Controller found that the department failed to adequately prepare for these events due to a lack of leadership.

Rise and other activists who believe in shifting resources away from policing and toward combating poverty, housing inequality, and other disparities say the changes don’t go far enough.

“The protection and care of community members is not ‘not a chokehold’ … it’s fully funded services,” they said.

Philadelphia City Council is currently considering the fiscal year 2023 budget. Mayor Kenney’s current proposal includes $782 million for the department, up from $729 the year before according to budget documents.

Moving forward

Keyssh Datts still tears up thinking about the 2020 demonstrations – a reflection of the panic and confusion that ensued as civilians and law enforcement officers clashed in the streets.

“Almost as if they were at war with us,” they said.

Philadelphia is grappling with an unprecedented gun violence crisis, and there’s a wide range of opinions among Black residents about how involved police should be in solving that problem, with the threat of police brutality a frightening reality for many.

“Every day we can become George Floyd.” Khalif said. “We can’t afford to go to sleep, there’s too much on the line.”

He said law enforcement will never make neighborhoods safer the way that on-the-ground community groups can.

“Community solves issues in our community,” he said. “We know who the people are … We stay visible in our community. We stay active in our community. We have respect in our community.”

More restorative justice programs that help young people resolve conflict and more therapists in schools could help, Datts suggested.

Rise finds hope in mutual aid, a movement centered on everyday people sharing resources — for example, community fridges, or raising funds for someone’s cash bail.

It’s not a new concept, there have always been grassroots activists and underground care networks in Philadelphia, they said. But the highly visible nature of the George Floyd demonstrations inspired those efforts to grow and thrive in a new way.

“Philadelphia has set the precedent for state-sanctioned violence. From the MOVE bombing to Walter Wallace, we’ve seen this extraordinary infrastructure of harm,” they said. “But within that, we also see some of the most radical and visionary care. It’s made an impression on me that I can’t put into words.”

Rise wants to see a groundswell of support for young people and a coordinated effort to bring them into the gun violence prevention conversation.

“The solutions that I see both to the loss, the murder, the senseless killing of a person like George Floyd is the same answer to the senseless killing of Philadelphia youth,” they said. “Youth organizers in Philadelphia really give me a lot of hope … those extraordinary networks of care and connection are the ones that inspire me on the daily.”

If you or someone you know has been affected by gun violence in Philadelphia, you can find grief support and resources online.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.