Giant Heirloom Market took a gamble on Philly’s Market East. Here’s why it failed

The grocery store with Pennsylvania roots is leaving after only three years.

Listen 1:10

Giant Grocery’s Heirloom Market concept was tested in Philadelphia. (Kristen Mosbrucker-Garza/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

The Giant Heirloom Market, a compact grocery store focused on selling fresh food, sushi and beer on tap plus a coffee shop, aimed to bring the boutique shopping experience to Philadelphia neighborhoods.

Yet some would argue the experiment failed in one community as the Market East in Center City location will close permanently by year’s end.

For now, it was a risky bet that didn’t pay off for both the current building owner, a real estate investment trust in San Diego, California, and the tenant, a grocery store with roots in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

“I think this is more of a mismatch in location and maybe a bit of an optimistic bet for the area but it was probably ahead of its time,” said Jessie Handbury, an economist and associate professor of real estate at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania who specializes in urban economics.

That gamble came with the support of public subsidy. Taxpayers have already given a break to the building owner for years and the deal extends another 11 years in exchange to help make the retail corner active and not sit vacant, because it’s an extension of the Fashion District shopping mall.

There is one group that did place a winning bet: the investors who bought the ground floor retail property out of bankruptcy, who secured an anchor tenant then sold the property at a profit to the highest bidder.

As Philadelphia leaders prepare to showcase the city on the world stage in 2026, there’s potential for yet another stretch of vacant storefronts to greet pedestrians walking from City Hall to the Liberty Bell – a stark contrast to the city’s ambitions — despite efforts to attract businesses through economic incentives.

And it’s unclear how successful the next tenant of that property might be based on the struggles documented in public records obtained by WHYY News, which include health inspections to retail theft reports on file with the police department.

Giant Grocery Co. declined multiple interview requests for this story, opting instead to respond to a series of written questions.

A highly curated experience

Giant launched its Heirloom Market concept in 2019, opening locations in the Graduate Hospital neighborhood, University City and Northern Liberties.

The company continues to operate larger, more traditional locations in less dense neighborhoods within the city limits and nearby key public transportation hubs along Broad Street, both north and south of City Hall.

These smaller Heirloom Market stores were meant to encourage shoppers to gather, linger and spend.

It was designed for tourists, commuters and even a growing residential population in Philadelphia’s urban core. The stores often carried local small business products like breads and chocolates curated to reflect the character of different neighborhoods.

Not everything went as planned. A previous bid to build a Queen Village neighborhood Heirloom Market fell through on South Street.

In 2021, Giant opened the Market East store.

Now just three years later, it will shutter permanently on Dec. 28 at 7 p.m., according to the company’s Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act letter to the state of Pennsylvania.

Giant occupied a space that’s technically an extension of the shopping mall now known as the Fashion District and previously as The Gallery.

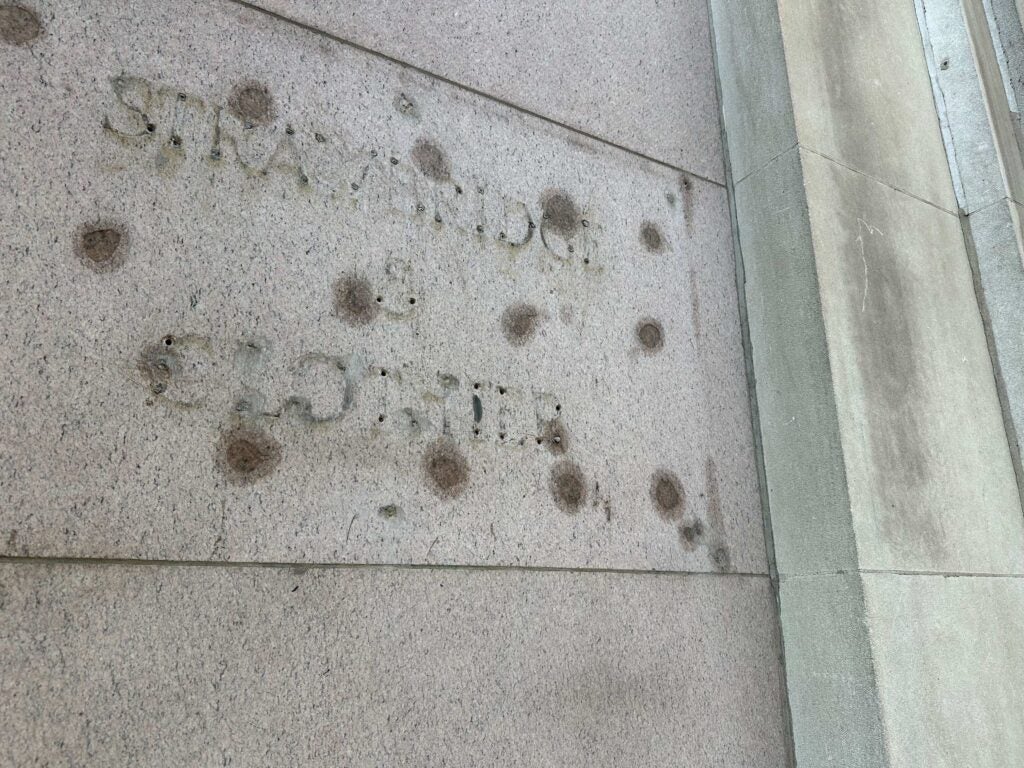

Built with a limestone facade in 1931 for $10 million, the building was once a Strawbridge & Clothier department store, with extra flourishes to compete with Wanamaker’s store down the street closer to Philadelphia City Hall.

Over the years, the lower floors remained retail and the upper floors were what’s known as Class B office space, that’s one step below the highest rent per square foot, or Class A.

Pennsylvania Real Estate Investment Trust, known as PREIT, held on to ownership of the bottom two retail floors until one of its Chapter 11 bankruptcies in 2020.

That’s when it was scooped up for $5 million by an entity affiliated with Philadelphia-based Alterra Property Group, which spent at least “several million dollars” to renovate the property for the future Giant Heirloom Market lease, according to bankruptcy documents and an interview with the Philadelphia Business Journal.

Just two years later, in 2022, Alterra sold it to an affiliate of Realty Income Trust of San Diego, which still owns it today.

It’s likely the store lease was signed during the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic when economic uncertainty was at an all-time high, said Handbury, the economist.

“The downside of the bet was pretty severe. My guess is that this wasn’t an economical operation for Giant to be running and they were losing more money running the operation than they would be just buying out the lease,” she said. “The plan could have been for Giant to act like an anchor but if there’s not enough foot traffic in that area generally, then there’s no foot traffic for that anchor to attract.”

Will a new business bet on Market East?

It’s unclear whether another commercial tenant will take over as a sublease, considering the property’s condition.

The grocery store did promise state and city officials that it would “look to assign or sublet the premises to any other qualified or permitted party with the consent of the landlord.”

But a casual visitor to the Market East grocery store might notice several individuals experiencing homelessness within 25 feet of the front door that opens to Market Street — a scene observed on a recent weekday in November. Those same individuals are often visible from the store’s cafe area, through its large front windows.

This familiar sight is reflective of broader challenges in Center City and has been for many years.

Public records reveal struggles inside the store too, such as a steady stream of retail theft and persistent infestations of rodents and insects.

In addition, someone from the 801 Market St. building reported various theft issues to the Philadelphia Police Department dispatches 73 different times between March 2021 and November 2024.

Inside that figure, 52 calls were for theft of at least $200 or greater value, which is at least $10,400 of stolen goods, over a three-year stint as a minimum estimate of retail losses.

During the month of October 2024, there were eight reports of theft at the property for products worth $200 and greater, which is a minimum loss of $1,600, police records show.

Retail theft is known as shrinkage and all companies deal with it as a cost that’s baked into the business model. However, it seems the risk may have been underestimated — until now.

Matt Kelley, senior vice president of business and market development at LiveView Technologies in Salt Lake City, works with retailers on mobile security camera systems.

“Some of our customers say theft has dropped off in general, but to what degree we don’t know because a lot of time it’s severely under reported,” Kelley said. “Shrink is a percentage of top line sales. So, I think that companies have done a really good job of trying to slow down the growth of theft relative to sales growth. If shrink grows at a slower rate than sales you’re going to see the percentages [go down] and their perception is that theft is getting better but it might not be getting better.”

Often, the public will watch videos on social media of retail theft and get angry, he said.

“The real question is how much theft is worth a person’s life. Is it worth a $20 item for someone to stop that individual and be murdered? Some of these individuals are very violent and when they’re cornered, when they’re threatened, they can lash out,” Kelley said. “Is it worth that stolen item for the violence that happens to the security guard, to the employee, to a customer nearby? What most stores have said is that it’s not worth it. What we’d rather do is deter people from the beginning. And be able to have higher resolution images from video to identify their faces.”

While the grocery retailer is pulling out, that doesn’t mean businesses can’t coexist when there are communities of individuals experiencing homelessness outside their stores – if the store is willing to build partnerships.

One professor at Drexel University has spent decades working at a nonprofit organization who helps individuals find housing, then mental health resources. He’s now a business professor.

Damian Salas is an assistant teaching professor and associate dean of academic partnerships at the Close School of Entrepreneurship at Drexel University.

“I think part of selling food is they really needed the community to be involved in the development, in the planning stages. That’s easier said than done, maybe they did, but it doesn’t sound like they truly knew who their customers were or how they were going to be engaged. I think they missed that opportunity,” Salas said. “What we call, in entrepreneurship, that product market fit, I think was just a little bit off. I think they need to do a little bit more work around building community engagement as part of their launch.”

Salas said some companies dealing with extensive retail theft have gotten creative, like Wawa in University City. Instead of a traditional corner store at 34th and Market Street, where there were issues with theft, now everything is ordered by a customer on a kiosk and workers deliver products.

“There’s just kiosks of stations with touchscreens where you order everything from sandwiches to gum to a Tastykake or whatever it is,” he said. “But I’m not sure that’s even possible within a bigger supermarket. But the point is that [the company said] we have a problem. Let’s solve the problem by doing this.”

Philadelphia’s retail theft situation

Retail theft is not just an issue in Center City, it has increased significantly in recent years citywide, records show.

In 2013, there were 129 retail thefts citywide during a two week span of Nov. 11th to Nov. 17 – the 46th week of the year. There was a slight uptick for several years thereafter and then a downward trend but not much of a difference, police crime data shows.

But in 2019, there were 243 retail thefts during the Nov. 11th to Nov. 17th time frame — a notable difference. And while there was a slight dip in 2020, likely when retailers were closed because of the COVID-19 pandemic, that has risen considerably.

In 2022, there were 298 retail thefts during that same two week stint, the next year there were 317 thefts. And in 2024, there were 406 retail thefts citywide over that same metric, a prior two-week period.

On an annual basis, retail theft has grown from 6,433 crimes within city limits between January and mid-November in 2014 to 19,692 during the same time period in 2024.

Critics of the Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner point to his guidance he gave to attorneys in 2018 to charge summary offenses in retail theft cases if the merchandise is worth less than $500.

Krasner has since created a retail theft taskforce and decided to change internal policy to target and prosecute theft rings fleecing retailers.

In urban environments, retail theft can be a sticky issue because employers weigh the value of the goods stolen with the likelihood that a bad actor will be violent towards a customer, employee or security guard.

“If you don’t have enough [police] for coverage you’re not going to be able to respond and that’s why you see retailers in urban environments having to lock up products or do other mitigation tactics to try and reduce theft, if not, you see what’s happened with certain retailers where you have to close a location because it’s not profitable,” Kelley, the tech startup executive, said. “That goes back to the enforceability issue, if they’re not going to prosecute why would you spend your time putting your people in harm’s way potentially to stop somebody who is stealing $900 worth of product.”

Historic properties come with pests

There are 16 different inspection reports on file with the City of Philadelphia Department of Health Office of Food Protection that show a pattern of persistent health code violations at the Giant Heirloom Market, between 2021 and 2024.

Before the grocery store opened in November 2021, its health inspection report was largely clean with recommendations to replace missing ceiling tiles, dust construction debris and to remove plastic from equipment.

But by January 2022, health inspectors were on the scene again in response to an unidentified complaint, although no violations were observed.

The store has been cited with numerous health code violations since June 2022, which include issues like mouse droppings in both food preparation and storage areas, fruit flies in the deli prepping section and entry points that are not properly sealed that enabled pests to easily enter the premises.

Despite inspections being conducted regularly to address these problems, issues continued to persist over time, such as infestations and unsanitary garbage areas as well as unresolved problems with the store’s restrooms.

Inspectors have noted instances of gnawed food packages and a mouse infestation by November 2022 with violations continuing into the year 2023.

Both June 2023 and November 2023 periods passed with the store still not meeting the standards and having unresolved issues that added to its troubled past, which ultimately led to its closure.

The most recent health inspection report of the store was in October 2024 and many of the longstanding issues persisted at the grocery store.

The Hissho Sushi operation inside the Market East grocery store was inspected by the city in a series of different reports. Many of the issues were similar, including the mouse infestation, fruit flies and even live roaches in a trap observed by health inspectors in November 2023. It suffered from similar problems with the building structure, such as peeling paint, cracked floor tires and lack of sealed rooms.

Center City is no food desert

The closure of the Giant Heirloom Market is unlikely to push the urban core into a food desert.

Handbury, the University of Pennsylvania researcher, contributed to the study at the intersection of food deserts, real estate and public policy after significant federal investment to reduce food insecurity.

Researchers found individuals are likely to visit a nearby grocery store when it enters the market nearby their home, but the presence of a store does not change the nutritional quality of the food they purchase nor eat.

“We found that even if households face the same food options, poorer households tend to pick less healthy options because those options fit more within their budget,” she said. “Particularly when it comes to these perishable food items, for the store to be able to offer high quality fresh foods, they need to have sufficient demand for those products so they can actually get the inventory off the shelf while it’s still fresh without losing money.”

Meanwhile, competition among grocery stores has intensified in Philadelphia, particularly in Center City.

“We understand that customers have a lot of choices about how and where they want to shop which is why we offer both in-person and online grocery,” said Giant Grocery Co. spokesperson Ashley Flower in an email. “Philadelphia remains an important market for the company.”

Giant has operated in Philadelphia since 2011 and continues to expand with new stores in Andorra and on South Broad Street scheduled to open on Dec. 13. None of these new ventures will be Heirloom Markets.

“This is simply a business decision, only made after a thorough assessment and efforts to improve performance,” Flower said. “Unfortunately this store has not performed to our expectations and when coupled with the challenges we and others have faced in the neighborhood, it no longer makes sense to continue operating at this location. Things like local business conditions, safety and foot traffic, among others, all have an impact on a business’s operations.”

While the Fashion District is taxpayer subsidized, the grocery retailer itself did not accept any economic incentives since it opened in 2021, even federal paycheck protection money to pay workers, according to the company.

The Market East store employed 61 people as of Nov. 5, with an average weekly payroll of $28,000. Workers were offered equivalent positions with the same pay and benefits at surrounding stores in Philadelphia as part of the closure agreement.

As of mid-November, 84% of employees accepted jobs at the other locations. Any employees leaving the business are expected to be paid until Jan. 4.

The company estimated that the store closure will mean a loss of $256,911 in tax revenue for the city of Philadelphia but expects “the opening of our South Broad Street location later this year should more than offset that lost tax revenue.”

Exact details of the Giant Heirloom Market lease term were not immediately available; the company declined to share such information publicly.

But real estate experts suggest it’s highly unlikely that the lease was three years long. A highly visible anchor tenant in a commercial building typically signs leases between five years to 10 years long, if not 15 years.

Which means that Giant could still be on the hook to pay monthly rent to the property owner for the entirety of its lease term, just like an apartment lease.

“We don’t disclose the costs of our projects but as with any new store, it was a significant investment,” Flower said. “While the details of our lease agreement are confidential, we did sign a multi-year lease agreement.”

Giant Company has more than 35,000 employees across Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia and West Virginia operating 193 stores. It was founded and is still headquartered in Carlisle after 101 years in operation. It’s now owned by Ahold Delhaize USA, the American subsidiary of Koninklijke Ahold Delhaize N.V., a publicly traded grocery multinational in the Netherlands.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.