‘They’re scared’: Immigrant students in Delaware fear losing their safe haven at school amid new Trump-era crackdown

Some First State districts have adopted protections for undocumented students, but advocates want state-level action to protect all students.

Listen 2:44

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers wait to detain a person, Monday, Jan. 27, 2025, in Silver Spring, Md. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

This story was supported by a statehouse coverage grant from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

From the start of President Donald Trump’s second term, his executive order on immigration enforcement has reignited fear and uncertainty among immigrant communities across the nation.

Under former President Joe Biden administration’s immigration policy, officers were not permitted to arrest migrants at what were called “sensitive locations” like churches or schools. The Trump administration swiftly reversed that policy and will now allow Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers to access those locations. That’s raised concerns for immigrants, leaving students, families and educators grappling with the potential implications of federal agents targeting students.

While concerns have risen since the inauguration, the fear isn’t new. In 2020, Rony Baltazar-Lopez, a former school board member in the Milford School District, attempted to preemptively address such scenarios. Baltazar-Lopez, the first Latino to serve on Milford’s board, proposed a policy aimed at protecting undocumented students and ensuring the district’s schools remained a sanctuary. Despite his efforts, the policy failed to pass.

“I wanted to be preemptive and make sure that we had something in place for the school district because I had seen that other school districts like Christina School District and Red Clay, for example, they both had some type of policy or resolutions that affirmed their stance for immigrants and for undocumented students,” he said. “When we talk about undocumented students, it’s not just them that are hurt by these [executive orders]. It’s also the entire classroom. When you see your friends [or] your students, if you’re a teacher, being removed, it really affects the morale and environment around everybody.”

His proposed policy would have required judicial warrants for any federal agents requesting access to student records or entering school grounds. However, the board at the time dismissed the need, citing existing federal privacy laws like the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act.

He believed that relying on existing federal laws was not enough.

“They didn’t think it was necessary and at one point it was stated by the school district that FERPA already guarantees [protections],” said Baltazar-Lopez. “My inclination was to kind of make it a forceful policy or resolution to make it well known that we were going to stand for and protect undocumented students.”

When ‘sensitive locations’ are no longer safe

Fast forward to today, Trump’s undoing of the Biden-era protections for schools, churches and hospitals has sparked heightened fear in marginalized communities.

A recent statement from the Department of Homeland Security emphasized the administration’s intent to expand enforcement operations, a move that many argue puts vulnerable populations at greater risk.

“This action empowers the brave men and women in CBP and ICE to enforce our immigration laws and catch criminal aliens—including murders and rapists—who have illegally come into our country,” said a DHS spokesperson in a statement issued earlier this month. “Criminals will no longer be able to hide in America’s schools and churches to avoid arrest.”

Reflecting on the failed policy in Milford, Baltazar-Lopez emphasized the importance of school districts taking proactive steps.

“Not having a policy leads to ambiguity,” he said. “I think it will provide some comfort and would release some students and families from having anxiety and fear.”

The Milford School District did not respond to questions about whether they are revisiting the policy that Baltazar-Lopez previously tried to pass.

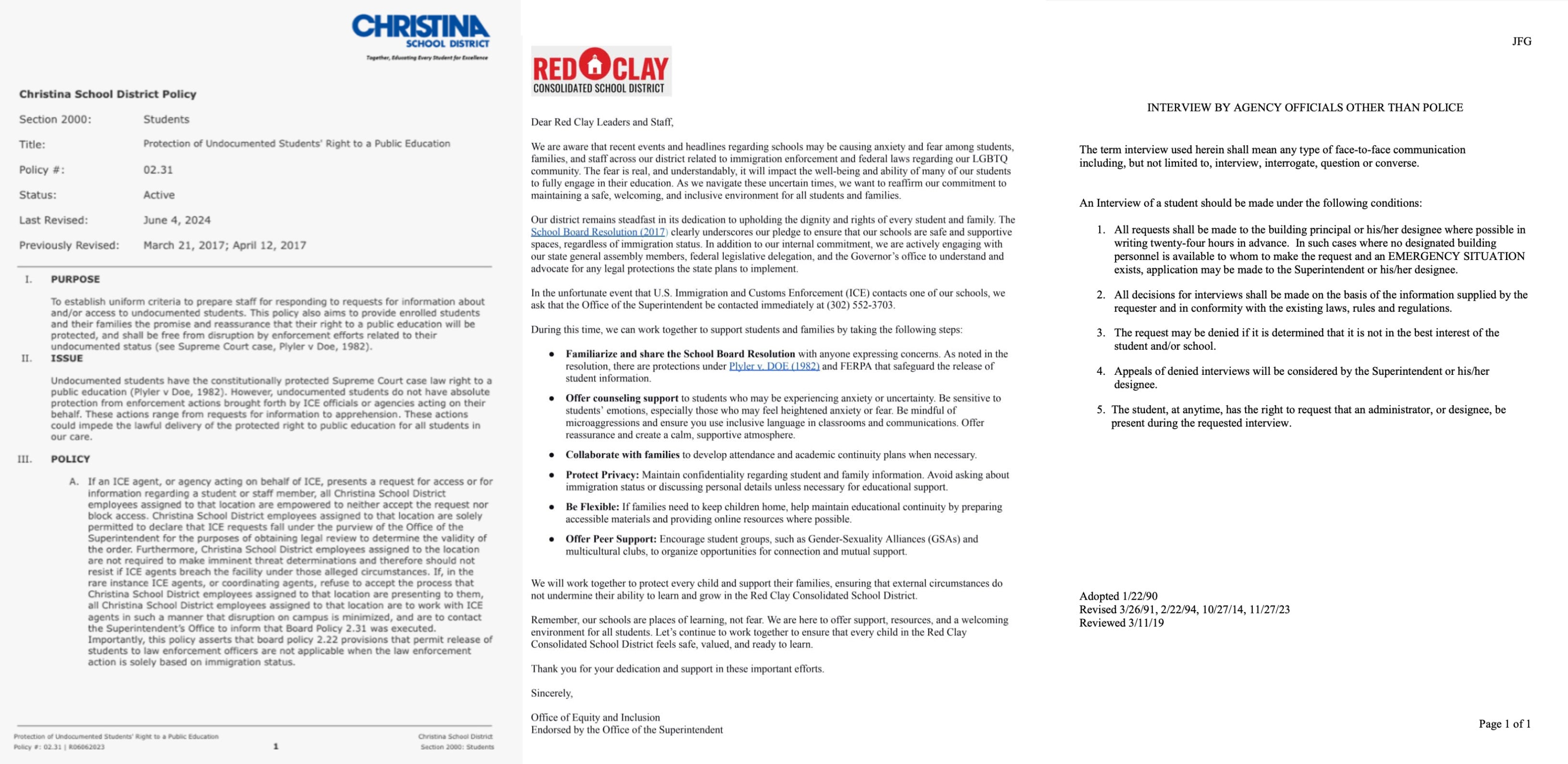

Other districts in the state have implemented some protective measures. Christina School District’s policy, introduced during Trump’s first term and now under revision, outlines clear procedures for handling ICE requests while safeguarding student rights. Grounded in the 1982 Supreme Court ruling Plyler v. Doe, which guarantees public education for undocumented students, the policy aims to prevent disruptions caused by immigration enforcement.

Similarly, Red Clay Consolidated School District adopted a resolution emphasizing student privacy, counseling and academic continuity, reaffirming its commitment to maintaining a safe, inclusive environment under Plyler v. Doe and the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974. The district recently issued a statement reminding parents and the community that students remain protected under these policies.

ASPIRA of Delaware CEO Margie Lopez-Waite shared how her school implemented a procedure in 2017 to address requests from government agencies.

“It primarily … gives our main office team members guidance on how to handle any situation where [a] government official, government agent comes into our school requesting to speak to one of our students,” she said, emphasizing that the procedure ensures all requests are funneled directly to her office. “That way we have … one central person responsible, and that way I can ensure that they have the proper documentation, the proper authorization, that parents have been notified.”

Lopez-Waite drew parallels between immigration protections and the COVID-19 pandemic, emphasizing the need for statewide policies.

“I sort of equate it to what we dealt with during COVID, right? When it came to something like COVID, in many instances that could not just be left to local control. That needed to be decisions made at the state level to protect the entire state,” she said. “This is another situation where every district and charter is looking for guidance, we’re looking to each other, but ultimately we’ve got to get it from the state level.”

She urged the Delaware Department of Education and state leaders to implement statewide protections.

While districts and charters show commitment to protecting students, schools like Indian River School District still rely on a policy from 1990, which was last revised in 2023. Community members argue the latest revision falls short, lacking clear language on handling ICE or immigration enforcement at schools.

Emotional toll: Teachers left to answer the tough questions

Classrooms have become places of uncertainty, where students struggle to focus, their anxiety overshadowing their ability to learn. Many confide in teachers, asking difficult questions: What happens if ICE comes into their school? Will they see their parents again? Was this morning’s hug the last?

Jennifer Nein, multilingual coordinator at North Georgetown Elementary in the IRSD, describes this feeling as eerily familiar. She recalls a time 20 years ago when immigration enforcement swept through southern Delaware, leaving similar scars on immigrant communities.

“Close to 20 years ago, they did a massive sweep in Georgetown … We had kids coming into school crying because their dad had been, you know, they’d come through the window in the middle of the night and their dad had been taken or we had kids going home and no parents at home,” she said. “I mostly work with kids in small groups so they feel very comfortable talking to us.”

“They’re telling us that they’re afraid that their parents are going to be taken. They’re scared, you can see it and I don’t know how to get them to focus on learning when these poor babies are just so worried about what’s going to happen to them,” she explained. “I mean their whole life literally could be just turned upside down.”

The strain on teachers is undeniable. Many say they hold back tears in front of students, only to break down in private. During lunch, they discuss policies and share ways to support their students, all while navigating the emotional weight of providing reassurance in an atmosphere of fear.

Keaira Fana-Ruiz, a middle school English teacher at ASPIRA, echoed the emotional strain.

“It has been difficult and very emotional. There have been tears within informal one-on-one conversations between teachers, also more formal [settings] like going to team, grade-level meetings,” she said. “Things have come up, especially when we talk about individual students and their concerns and what we’re noticing. So it’s been taxing, it’s very emotionally taxing.”

“I feel powerless. These are my kids, they’re my school babies, they’re not just my students,” she said. “Oftentimes, people say that teachers are champions for students, we’re their heroes, but I don’t feel like a hero — I feel very much powerless.”

A call for statewide action

As Gov. Matt Meyer took office earlier this month, he pledged to protect Delawareans. Now, students and families are waiting to see those words translate into meaningful, proactive action.

“I also want to make this absolutely clear: If the president or his administration or anyone try to take away your health care coverage or further restrict your reproductive rights or undermine our schools or try to come into our communities to harass folks who came to our country and our state in search of a better life, if they do these things, I will use every power you vested in me as governor to protect our residence, to protect our livelihoods, to protect our values,” Meyer said in his inaugural address. “That is my pledge to you.”

Advocacy groups and community leaders are calling for Delaware to adopt statewide protections. While some districts have established new policies, others like Indian River School District still rely on older policies lacking clarity on handling ICE or immigration enforcement.

For now, families remain on edge, with misinformation and fear spreading rapidly. But advocates like Baltazar-Lopez and others remain committed to ensuring that every student, regardless of immigration status, has the right to learn without fear.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.