Communities can’t solve Philadelphia’s inequitable vaccine rollout alone

In Philadelphia, the individuals and organizations doing the work are doing it for free without any funding from the city for vaccine outreach.

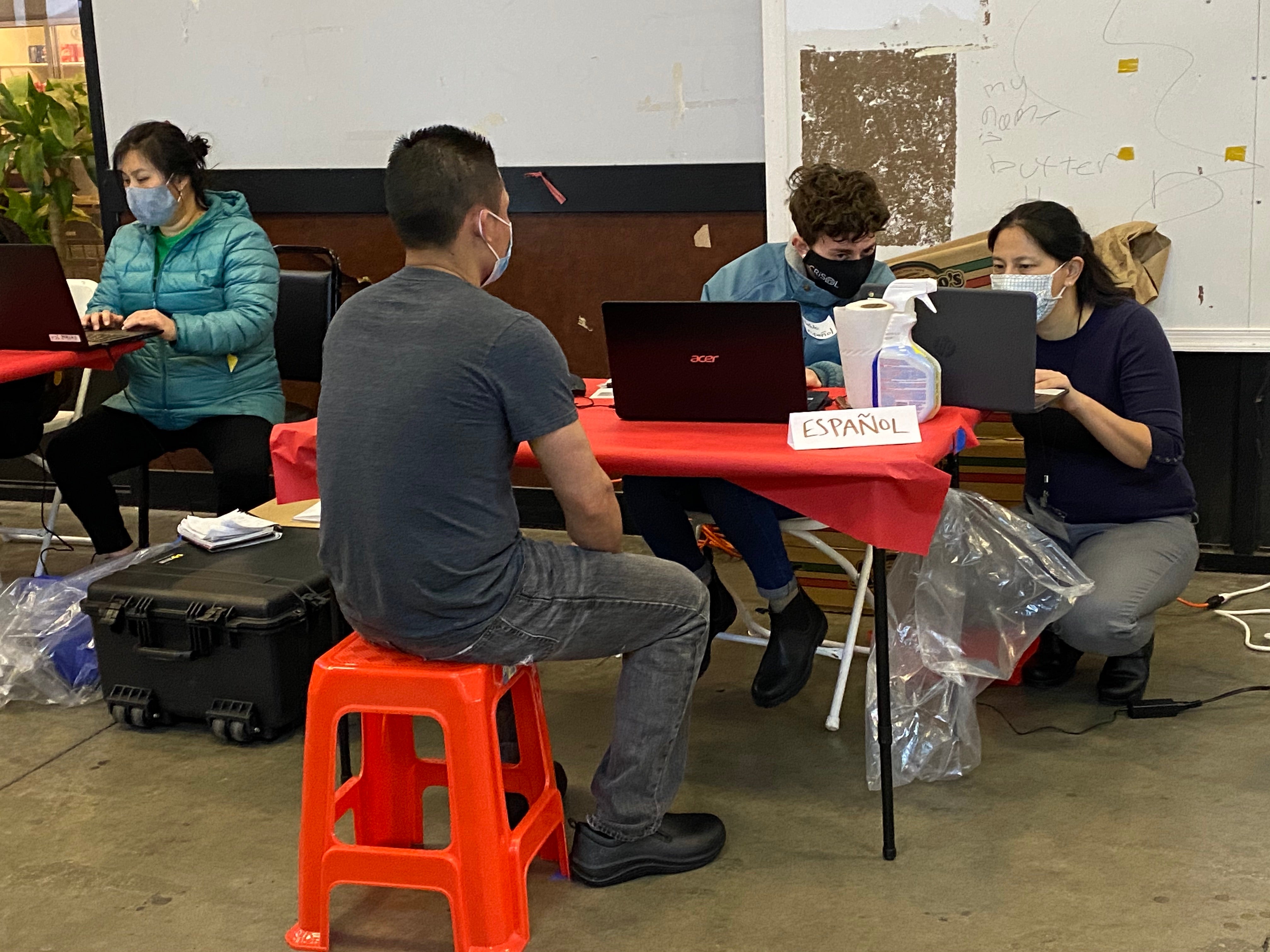

A pharmacist giving a community member the Pfizer vaccine on March 21 in South Philadelphia during Juntos and VietLead’s organized vaccination event. (Courtesy of Thy Vu)

Ask us about COVID-19: What questions do you have about the coronavirus and vaccines?

After hearing stories from family members who waited for hours to get the vaccine, Kim Dao was certain that it’d be months until she got hers. But even when time was not an issue, she was lost and confused about how to even begin getting there.

The 77-year-old Vietnamese immigrant who has retired and lived by herself didn’t know how to navigate the online registration system that beleaguered even fluent English speakers.

But on Sunday, March 21, she got the first shot of the Pfizer vaccine through Sunray Drugs in Oregon Plaza, South Philly, with the help of VietLead and Juntos, both organizations serving immigrant communities in Philly.

“I have some problems with my legs so I wouldn’t be able to stand in line for that long. It’s very good that I didn’t have to wait too long here,” she said. Dao got her shot within 20 minutes of arriving at the clinic.

The event was the first vaccination clinic that VietLead and Juntos organized together to bring the vaccine closer to home.

Within a short walk or bus ride to many immigrant Philadelphians and close to a grocery store and nearby restaurants where people work long hours and may not be able to go far for a vaccine appointment, the Oregon Plaza location was selected intentionally by organizers — one of many choices made with access in mind.

“People know they should make time for the vaccine but people also need to work, eat, and make a living. If the city can’t raise the minimum wage, they should at least bring the vaccine to the people,” said Emily Tran, VietLead’s health manager.

The majority of more than 230 people vaccinated that day speak solely Mandarin, Khmer, Cantonese, Vietnamese or Spanish — and have limited internet access. They are eligible for the vaccine but their access has been limited by the design of the Philadelphia Department of Public Health’s vaccination program.

Nga Vu, VietLead’s health coordinator, says the city’s registration system discriminates against people who don’t have internet access and have limited English proficiency, which is the case for most migrant workers and their families.

With overcoming these barriers in mind, VietLead staff drew up a registration plan for elders and immigrants to make sure that language difference or tech proficiency, or even needing more information was not an issue preventing our community members from getting a vaccine appointment.

“We spent a long time talking to each person on the phone to explain what we’re doing, convince them to take the vaccine, then remind them to be on time,” Vu said. “For five days, we couldn’t do anything else besides preparing for our clinic.”

Our experience reveals that getting people vaccinated — doing the education and outreach necessary to even get people signed up— requires a lot of time and labor, especially in communities of color.

But in Philadelphia, the individuals and organizations doing the work are doing it for free without any funding from the city for outreach. The data on who’s and where’s getting the vaccine the fastest reveals a public cost to this ad-hoc strategy: a chasm that affects communities of color across the city and region.

Vaccination racism

Many organizations have already voiced their anger and frustration at the Philadelphia Department of Health and Commissioner Thomas Farley for a poorly executed vaccine rollout after months of empty promises to prioritize vaccine distribution and access to Black and brown communities in working-class and low-income neighborhoods.

As a direct service organization working closely with low English proficiency (LEP) immigrants and refugees, VietLead staff witnessed firsthand the chaos and confusion that the online registration process has caused to our elders and their family while navigating the system with limited language options and support.

The centralized and tech-heavy approach to the vaccine rollout ignores the reality on the ground for tens of thousands of Philly residents without access to the internet. Many work frontline and essential jobs, don’t speak English or lack the ability to travel long distances. Many simply can’t afford childcare or waiting in lines for hours to then be turned away even when they meet the criteria, as documented by Chef Ange Branca.

The department and the commissioner need to take into consideration these systemic barriers and put themselves in the shoes of the people. In a city where 30 plus languages are spoken at home, more than the national average, it took over a month before the city’s vaccine interest portal was available in languages other than English and Spanish.

Despite these challenges, Philadelphia residents have held up our end of the bargain.

We’ve listened to city health officials and stayed indoors, worn masks more often than other cities, heeded the call to vote early and by mail last November to reduce long queues at the polls, taken care of each other through mutual aid across the city and neighborhoods.

And yet what ended up happening on the city’s side with the vaccine rollout is a leadership meltdown.

- Multiple red flags with the notorious Philly Fighting Covid group and CEO were reportedly ignored and swept under the rug by PDPH Director Thomas Farley.

- Despite BIPOC accounting for 65.5% of the city population, the majority of vaccine doses administered have gone to white communities and wealthier ZIP codes.

The top-down, stringent approach from the department has favored white, educated, well-connected groups over the most impacted, disadvantaged ones. Moreover, it encapsulates the systemic racism that plagues the city and this country during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A public health system that gives different racial groups woefully different health outcomes is health apartheid. Perversely, the efforts to alter the inequitable course lean heavily on Black and brown community organizations for outreach and education without funding and communication. The groups who are left out of distribution are now expected to carry out the work for free, with no funding support from the city.

The Black Doctors COVID Consortium, most notably responsible for boosting vaccination rates in Black communities and closing the racial gaps, is still not funded by the city for its heroic and relentless vaccination work. While the consortium has received funding from the city for COVID-19 testing and is in the running to receive city funds from the next city budget, volunteers from the group have worked for months without this support.

Rebuilding trust in the community

When VietLead got the green light for the vaccine, we spread the word to sister organizations and shared the doses with the Latino, Khmer, and Indonesian communities. VietLead and Juntos staff used our extended connections with these communities to know where the gaps are and fill them.

For example, parking is a big issue, second to traveling time from home to the vaccination site. Oregon Plaza is a great place for the community-based clinic because it has an ample parking lot and a public hallway that allows VietLead to do outreach and education for people who happen to walk by.

There’s also the psychological aspect of seeing others get vaccinated and wanting to do the same thing. We paid attention to not only community members’ accessibility and language needs, but also their overall comfort level and ease.

“We want to make things as easy as possible for everyone. The labor is worth it because people can get the vaccine in a place they feel safe,” said Tran, VietLead’s health manager.

What that entails is the meticulous design of the limited space at Oregon Plaza to accommodate an efficient and fast-paced clinic environment that ensures social distancing and mask-wearing guidelines at all times.

With nearly a dozen volunteers at the event greeting people, checking their temperatures, giving directions, writing down interest forms for future clinics, answering questions about the vaccine, etc., no one was left confused or wondering what they had to do at every step of the way.

VietLead rented a new space for the rest station to make sure we keep each seat six feet apart from one another. Our volunteers stood at the entrance and gave out a piece of paper with a timestamp to people showing when they could leave the room and go home.

Next to the entrance, the Department of Labor’s representative had a table to offer resources about fair workweek, paid sick leave, and other workers’ protection information to the people waiting in the room, in English and Vietnamese.

One volunteer walked around and checked in with people on their voter registration status, and helped those eligible but unregistered complete their application on the spot.

Another volunteer handed out flyers about VietLead’s direct services program and how to contact us in the future.

The combination of direct service and public information distribution bolsters efforts to regain trust and access to the community. We fostered the cross-pollination of different public services that will deepen relationships with our community through this one-in-a-lifetime event.

In these unprecedented times, we still see hope, joy, and happiness beaming behind the masks of soon-to-be fully vaccinated community members who support the vaccine and public health measures that keep us all safe.

The PDPH has had more than ten months to work on a distribution plan that puts equity first and control back into the hands of the people who suffer the most from the pandemic. The vaccine rollout could have been the moment of unity and of neighbors and city residents coming together to solve not only their individual problems but the systemic ones that we all face.

I can see what that would have looked like because I saw it at VietLead’s vaccine clinic with my own eyes: Workers learning about laws that protect them from abuse and exploitations, citizens claiming their right to vote, immigrants owning the public space that understands their needs.

“It’s clear that the city prioritizes coming up with ways to mass distribute the vaccine over helping people understand how and why they should get vaccinated, but that’s not working for our community,” said Emily Tran. “Now they’re asking underserved groups to do the outreach work for free and I don’t think it’s fair.”

To rectify the social and economic consequences of these missteps, VietLead demands that the Philadelphia Department of Health:

- Fund outreach and education work from the ground up, starting with community-based organizations in priority ZIP codes;

- Respond to the needs of diverse communities and target neighborhoods with low rates of vaccination for mobile clinics;

- Investigate and audit its rollout plan to find out where and how disparities happen and implement remediating solutions;

- Simplify the registration process with an automatic appointment for anyone who qualifies according to the phases;

- Ensure language access at all levels in Spanish, Mandarin, Vietnamese, Arabic, Haitian Creole, and Khmer, and other top most spoken languages in the city.

Anh Nguyen is a community organizer with VietLead.

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)