What two starkly different Philly-area high schools tell us about how Pa. funds education

Two neighboring public schools show the inequity of school funding. “Schooled” looks into the forces at play, and how a lack of resources affects everyday life.

Listen 27:21

'I thought I was in High School Musical,' says Penn Wood student Paul Vandy, describing the first time he was at Lower Merion High School. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

This episode is from “Schooled”, a podcast production from WHYY that gives the insider’s story of public schools, through the eyes of students, parents, and educators.

Read and listen to the second episode.

Find “Schooled” on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

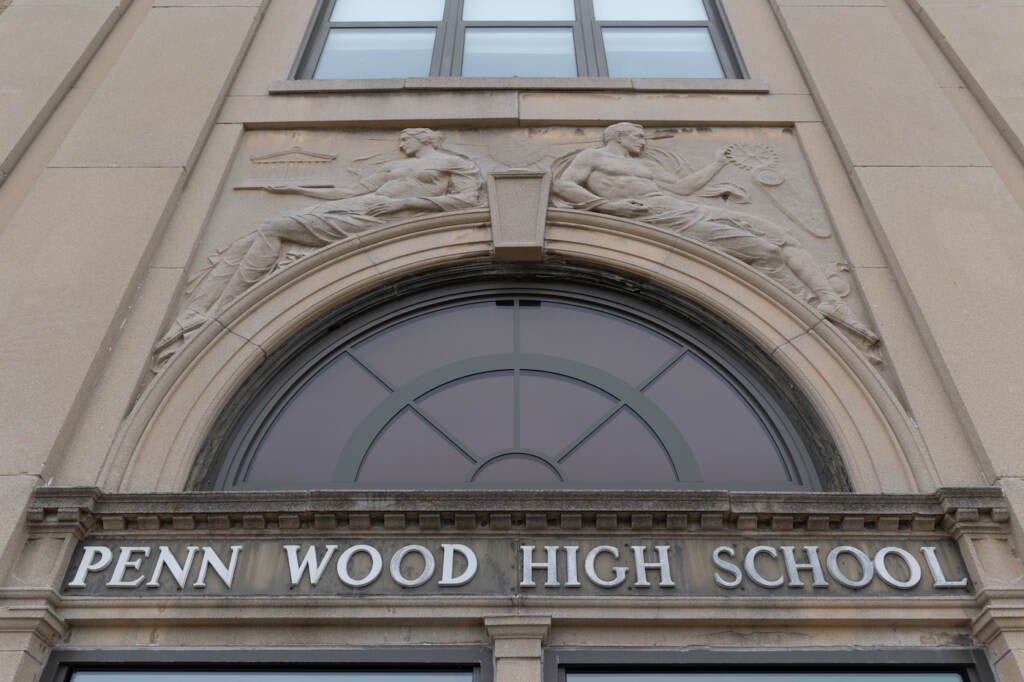

At first glance, Penn Wood High School, just a few miles outside of Philadelphia, looks like any other school.

Think long hallways lined with classrooms and glass cases displaying student artworks, clumsy still-life paintings, and heavy pottery.

A large quote painted on the wall says, “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.”

Right beneath it, a noisy fan churns the air. The school’s air conditioning isn’t working properly — the first sign of many that the building is in disrepair.

Bricks are loose or missing. Paint and plaster peel from the ceilings. A thermostat dangles from the wall. The library is so outdated it’s almost obsolete and the cafeteria is crowded and dingy.

Now, take a 20-minute drive to Lower Merion High School a few miles farther away from Philly. To students visiting from Penn Wood, the school felt like a movie set.

“I thought I was in ‘High School Musical,’” senior Paul Vandy says.

The architecture firm that designed this other school has an entire page dedicated to it on its website.

It boasts a college-style lecture hall, an 850-seat auditorium, a black box theater, a greenhouse, multiple gyms, a central courtyard, and a two-story library.

This dichotomy illustrates the problem with Pennsylvania public schools in a nutshell.

While some schools enjoy abundant resources, others are falling apart and barely functioning, affecting the lives of hundreds of thousands of kids and families across the state.

But now, a landmark court ruling could force the state to change how schools are funded, potentially bridging these gaps.

The problem with Pa. school funding

Large spending disparities exist between school districts across the United States because education in most states is funded, in part, by local property taxes. Since taxable wealth varies from one community to the next, so does the amount of money school districts can raise.

Compared to other states, Pennsylvania relies on local dollars to an unusual degree, aggravating the problem. Roughly 55% of school funding in the commonwealth comes from local sources, according to federal data. The national average is 10 points lower.

This reliance means while Pennsylvania spends more per student than most other states, this spending isn’t distributed equally. For example, Pennsylvania received an A letter grade from the New Jersey-based Education Law Center for overall education funding — roughly more than $4,300 more per student than the national average — but an F for distribution.

The center found the state’s distribution of dollars to be one of the most regressive in the country. High-poverty districts received roughly 20% less funding per pupil than low-poverty districts, according to the report.

As a result, disparities between Pennsylvania schools in rich and poor areas — which also largely fall along racial lines — are massive, and the state does little to fill the gap.

The result is a de-facto segregated school system that especially disadvantages Black and brown children.

This is why the William Penn School District, in southeastern Delaware County, has far less money than its wealthy neighbors and why it joined five other property-poor school districts to sue the state in 2016.

The district enrolls roughly 5,000 children across six boroughs, Aldan, Colwyn, Darby, East Lansdowne, and Yeadon. More than 80% of students are Black and more than two-thirds are considered low-income.

There are eight elementary schools, one middle school, a ninth-grade academy, and Penn Wood High School, where 20-year-old Nasharie Stewart graduated in 2021.

Nasharie, now a rising junior at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, has good memories of Penn Wood, where she excelled in her classes, competed in mock trial, and served as a student representative on the district’s school board. But these positive experiences don’t excuse the fact that her school was literally falling apart around her.

“It’s been the same building since the day it opened up, so it’s not in the best of shape,” she says, staring up at the building’s exterior with its intricate stone face.

The school was impressive when it first opened in 1927. It was built in an Italian Renaissance style by the same person who would later build the Pentagon and the Kennedy Center.

Maintaining this once-grand building has been a challenge, since money in the district is always tight. That’s even though the school’s district, William Penn, has one of the highest property tax rates in the state.

Property across the majority-Black school district is worth about $1.5 billion. Compared to nearby districts, that amount is minuscule. One has nearly four times as much wealth. Another 10 times. Both those other districts are predominantly white.

Because of William Penn’s relatively low property value, district officials say there’s no feasible way to bring in enough money to cover its needs through local taxes.

Judy Lee, Penn Wood’s principal, has worked at the high school for the last decade. She knows the building and its problems better than anyone — and a big one is overcrowding.

“Students share, ‘Dr. Lee, I don’t want to be in this space,” she says. “I’m sorry I don’t have any other space for you, so you have to go there.”

The building has been cramped since the district merged three high schools into one in the early 1980s as a result of the Brown v. Board of Education ruling.

If public education was supposed to be the great equalizer, Brown was going to finally deliver on that promise. But that didn’t happen.

Across the country, white families moved to avoid integration or enrolled their children in private schools instead. In some places, property values plummeted, starving schools of resources, and over time, many schools effectively re-segregated.

Students have to shout to be heard over the drone of the HVAC in Penn Wood’s smaller gym. Some students eat lunch here because the actual cafeteria is too crowded. Even with the gym used for overflow, there isn’t enough room for everyone to eat comfortably.

Then there’s the library. The small windowless room has a water-stained drop ceiling. Tiles are sagging or missing, exposing ductwork and wiring.

Another problem? There’s no librarian. When a student wants to use the library, they have to convince a teacher to give up their lunch or prep period to supervise them. Otherwise, the room remains locked.

Even when it was open during her time as a student, Nasharie says it wasn’t that helpful because it isn’t well-stocked and the books that are there are outdated.

The library has a mouse problem, too.

During the winter, Lee says staff with classrooms near the library found mice droppings on their desks every morning. One time, a mouse even ran through in the middle of the school day.

“The teacher screamed and stood on the chair and students were screaming,” Lee says. “It was just not conducive for our students’ education.”

The issue, she says, is the building’s foundation. It’s crumbling, creating openings for rodents to get in. Until that’s resolved, she expects the problem to keep happening.

“We are only using Band-Aids,” she says, pointing to a mouse trap.

All of this, the crowding, the crumbling, and the mice, make teaching and learning tough.

While the mice weren’t a problem when Nasharie was a student, she remembers lessons often interrupted over facility issues — like the time she was reading Shakespeare in English class and a ceiling pipe burst. Water gushed down, forcing her class to evacuate.

“Those minutes, they amount to a lot of hours, and that can really take a toll on what you’re able to learn,” Nasharie says. “Before you know it, you’re behind.”

Part of the problem, she says, is that students at other schools aren’t behind, they’re ahead. And they’re all trying to get into the same colleges.

She looks at the library’s many empty and dust-covered shelves.

“I feel like the world continues to change around us and our schools need to keep up with that,” she says. “Unfortunately our school hasn’t been able to keep up with that.”

Lee knows the facility situation is frustrating for students and teachers.

It’s frustrating for her, too. But without more money, there isn’t much she can do.

“Our school culture is basically unity because if we don’t work together, we’re not gonna make it,” she says.

That sense of unity is why Nasharie says she visits Penn Wood whenever she can.

“Growing up here, I’ve had to do the best that I can with what I have,” she says. “I think that translates really well into college when you’re in a new environment. Taking those same skills I had to learn here to survive here, I’m now taking to use in college to thrive there.”

Listening to her speak, the word survive jumps out.

Words like perseverance and resilience are often used as compliments to describe people and communities who experience frequent hardships. But these words fail to acknowledge the deeper issues at play like poverty and racism. Should children have to persevere just to make it through high school?

“When your school isn’t in the best of shape, it can make you feel bad about yourself and your own self-esteem,” Nasharie says. “It makes you wonder, ‘Why aren’t you worth the necessary funding to have what other schools have?’”

Some Pa. schools have mouse traps. Others have robots

School funding isn’t something the average kid knows much about, let alone the costs of running a school. But the issue is certainly on the minds of current students at Penn Wood High School.

Trinity Giddings and Paul Vandy are seniors. They spend a lot of time together, in the classroom and after school. They even co-host a podcast called “PENNding Funds.” The topic? School funding.

Paul is a representative on the district’s school board.

“A lot of times when I was trying to bring up issues, it always went back to, ‘Funding, funding, funding. We don’t have the funding for this or funding for that,’” says Paul.

During their freshman year, Paul and Trinity faced the state’s funding discrepancy firsthand when they took a 20-minute drive north to one of the state’s wealthiest school districts, Lower Merion, for a speech and debate competition. (You might have heard of it because of its most notable graduate, the late NBA superstar Kobe Bryant.)

When they got to the school for their competition, Paul and Trinity couldn’t believe their eyes.

This is the school with the college-style lecture hall, black box theater, two-story library, and more.

“Walking around, everyone from our school was shocked,” Paul says. “Everyone was saying like, ‘People go to school here?’”

Paul had never seen a fully updated school. “I thought it was like a fantasy experience because the ceilings were huge,” he says.

It was the little things, by comparison, that stuck with Trinity. She recalls seeing tables where students could eat lunch outside. “We’re like, ‘Oh, wow, that’s nice.” (Remember, her cafeteria is in the basement.)

“Their lockers were the size of refrigerators,” Trinity remembers. “You could sleep in there.”

And then there was the robot. The robotics team was testing out its latest creation when Paul and Trinity were there, maneuvering its crane arm to pass a basketball back and forth.

Penn Wood has its own robotics team, but if you want to build a robot, you have to buy the parts yourself, Trinity says.

Lower Merion has a lower tax rate than William Penn but brings in much more money thanks to its higher property values. As a result, Lower Merion spends $13,000 more per student each year than William Penn.

The difference in spending isn’t simply a matter of having extra things, like dance studios and robots.

There are also major academic differences between the two districts.

Lower Merion touts its liberal arts curriculum with more than 200 courses. Students can earn an International Baccalaureate Diploma, considered by many to be the most rigorous.

Penn Wood offers about a dozen advanced placement courses, but there’s no fancy diploma, and overall, class options are far more limited.

After the students from Penn Wood visited Lower Merion, they hosted a speech and debate competition at their school.

Trinity says there weren’t enough classrooms available, so some rounds took place in closets. Others were in the library — the one with the mouse traps.

She remembers kids laughing and making comments about the condition of her school.

“You just have to be quiet and not mention that it’s your school,” she says.

Paul was upset by what the students said.

“I’m not any different from any other student down the road, but knowing that they get opportunities that I don’t just because of how much money their parents have, you know it hurts,” he says. “You just feel like, ‘What can I do about this?’”

Paul and Trinity’s district is far from the only one struggling.

Research suggests the majority of Pennsylvania’s school districts are underfunded. One study commissioned by the state found the difference between what schools have and what they need to be $4.6 billion, a number that keeps going up.

And the study confirmed something else: Different children need different things.

More than 20% of William Penn’s roughly 5,000 students have a special education plan, and about two-thirds are low-income. These students often require more resources to succeed. Because of the way residential and school district lines are drawn, they’re often concentrated in low-income districts, exacerbating the issue.

That means the students who need the most often end up with the least.

“That’s what can really be disheartening when you’re looking at students who need additional support and you’re trying to find ways to get it to them and you don’t have the resources,” says Eric Becoats, William Penn’s superintendent.

Last year, about 30% of William Penn’s elementary and middle school students were found to be proficient in reading and less than 10% in math.

Statewide, roughly 90% of students graduate from high school in four years. In the William Penn School District, that number is closer to 80%.

In the affluent, majority-white district Paul and Trinity visited, the vast majority of students read and do math at grade level and the graduation rate is 97%.

The fight for change

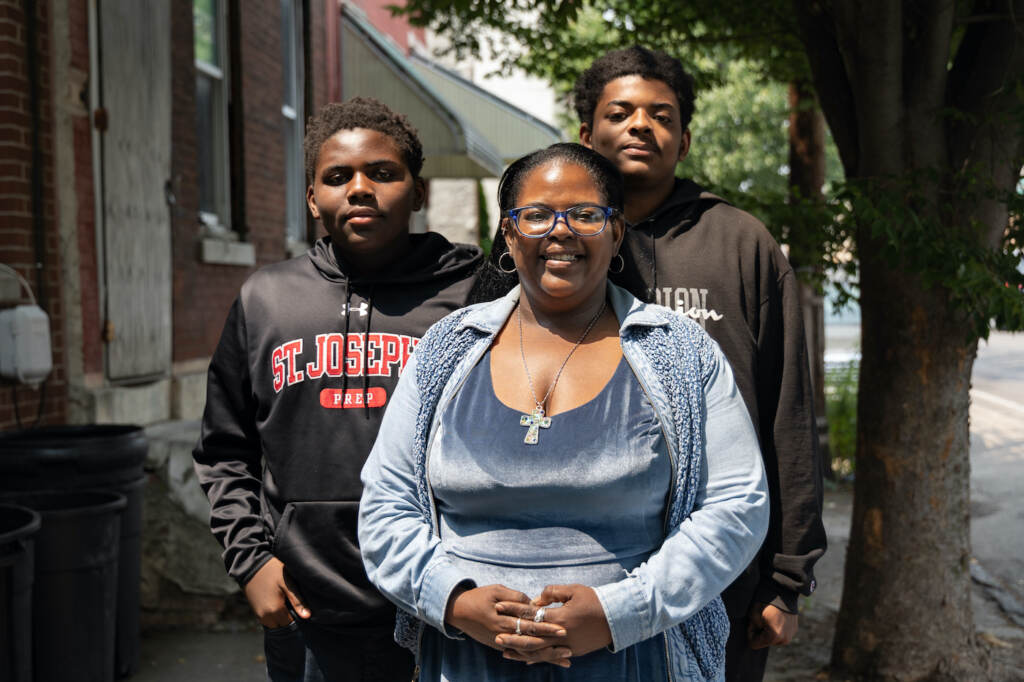

A lifelong Philadelphia, Sheila Armstrong has had her share of ups and downs, but she’s always landed on her feet. She credits her faith.

Her home is filled with Bible verses and encouraging statements. A blanket hanging on her wall says, “You are strong, beautiful, chosen, amazing, special, unique, lovely, creative.”

The words are there to inspire her, as well as her two boys, Skylar and Simeon.

Sheila also has a poster on her backdoor that says, “Excuses stop here.” That way, when her boys go out, they “can’t use no excuses.”

“If I ask and I’m fighting for an accountable system, then I too have to be accountable, and I’m teaching my sons they have to be accountable,” Sheila says.

It’s because of her boys, and because of that attitude, that Sheila was drawn into the fight for more school funding.

Sheila says she first got involved more than a decade ago as a concerned parent. It was 2012, and the School District of Philadelphia was in deep trouble financially. Cuts had to be made.

That was the year Sheila became president of the parent-teacher association at her sons’ school, Harrison Elementary.

“We found out that our school was going to get shut down,” she remembers.

Sheila knew she had to fight to keep the school open.

She collected petitions from residents and businesses in the community, totaling more than 5,000 signatures. She took the petition to the city’s state-controlled school board and urged them to keep Harrison open.

Despite her pleas, the board voted to close eight schools that day, including Harrison. They would close 30 in total.

“It felt like they didn’t listen to us at all,” she says.

Sheila was angry. “And I tell people anger can be a good motivation sometimes.”

She thought about what to do.

“And I said, ‘You know what? We need to sue, OK? All I know is people move when you sue somebody. We want to sue somebody,’” Sheila says.

Before long she was introduced to Michael Churchill. Michael, an attorney at the Public Interest Law Center, was the man to talk to. He had already sued the state over education funding more than a decade before.

“Philadelphia’s schools were being overwhelmed with problems that they didn’t have the ability to solve,” Michael says.

It was the late 1990s. Enrollment had increased and the district was teaching a growing number of students with low income. They required more resources, like bilingual teachers and special education services, but there was no funding increase from the state.

Around this time, Pennsylvania instituted standardized testing, and the results were alarming. Few students attending Philadelphia public schools could read or do math at grade level.

“I got involved in thinking that you can’t leave these problems to other people,” Michael says.

Michael, who was with the Public Interest Law Center by then, joined city attorneys and the district to sue the state.

In the case, he argued the more Black and brown students a district had, the less likely it was to receive its fair share of funding. Essentially, the state’s funding practices were racist.

Pennsylvania, the suit argued, had failed to meet its constitutional obligation to provide a thorough and efficient education for Philadelphia students.

Michael thought it was good grounds for bringing a suit, but the case didn’t go as he hoped.

The state Supreme Court decided the school funding clause in the state constitution was non-justiciable, a technical way of saying the court didn’t want to get involved.

By 2013, Harrison Elementary had closed and Sheila’s sons’ new school was dealing with significant budget cuts. Bigger class sizes, no libraries, and far fewer extracurriculars.

The district also fired many of its nurses. The ones who were left had to cover multiple buildings.

“With my son Skylar being asthmatic and having health issues, that was a big concern for me,” Sheila says.

Around this time, a Philadelphia student died from an asthma attack that started when she was at school and there was no nurse on duty.

At Sheila’s sons’ new school, she says there was a paper shortage, and textbooks and workbooks were out of date. Even those books were in short supply, so students weren’t allowed to bring them home.

The problem standing in the way of better schools, and better test scores, was always clear to Sheila — there wasn’t enough money.

She thought of education reform as first, dealing with the money.

“When the money get right, everything else is going to start getting right ‘cause then, they won’t have these excuses,” Sheila says. “‘We can’t do curriculum changes ‘cause ain’t no money. We can’t do building changes. Ain’t no money. We can’t do this. Ain’t no money.’”

Michael says districts had long thought the struggles they were facing were of their own making. That they weren’t hiring the right leadership or that their taxes were too low.

“Without ever thinking, ‘Hey, everybody else is struggling. The problem really is not what you’re doing, but what’s going on in Harrisburg,’” Michael says.

Even though his earlier attempt had failed, he was ready to sue the state again. It was time for him to go back to court, and this time, Sheila was coming with him.

“When I started this case, I thought it was going to be like a typical lawsuit, like a car accident or something,” Sheila says.

But it wasn’t. It would take close to a decade for Sheila and the other petitioners to get their day in court. At times, Sheila would feel stuck, at others attacked.

She wasn’t just fighting to reopen her sons’ school. She was taking on the state.

“This was so much bigger than me. This was so much bigger than my children, my family, the city,” Sheila says. “This was about all the kids in our state.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.