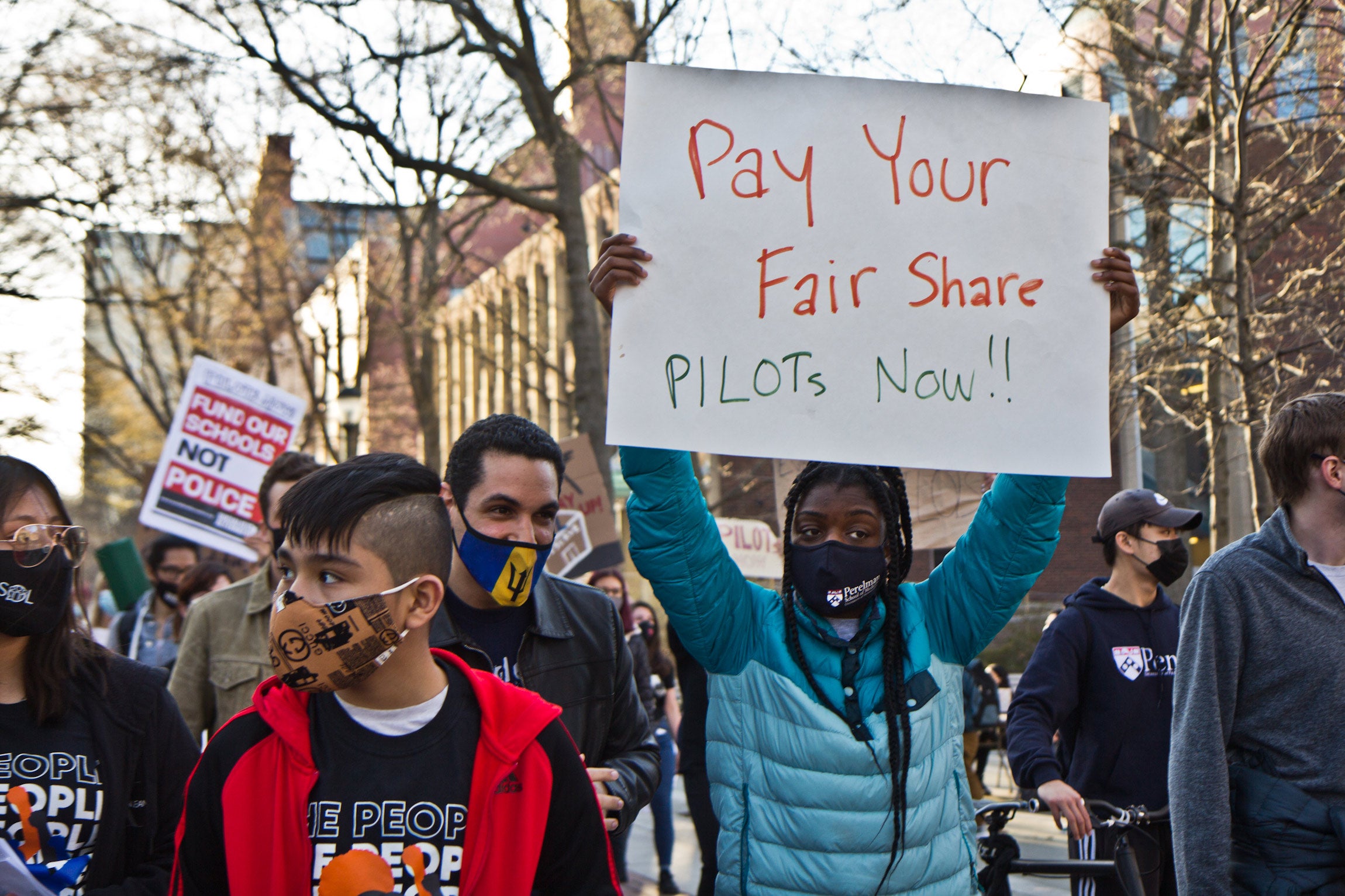

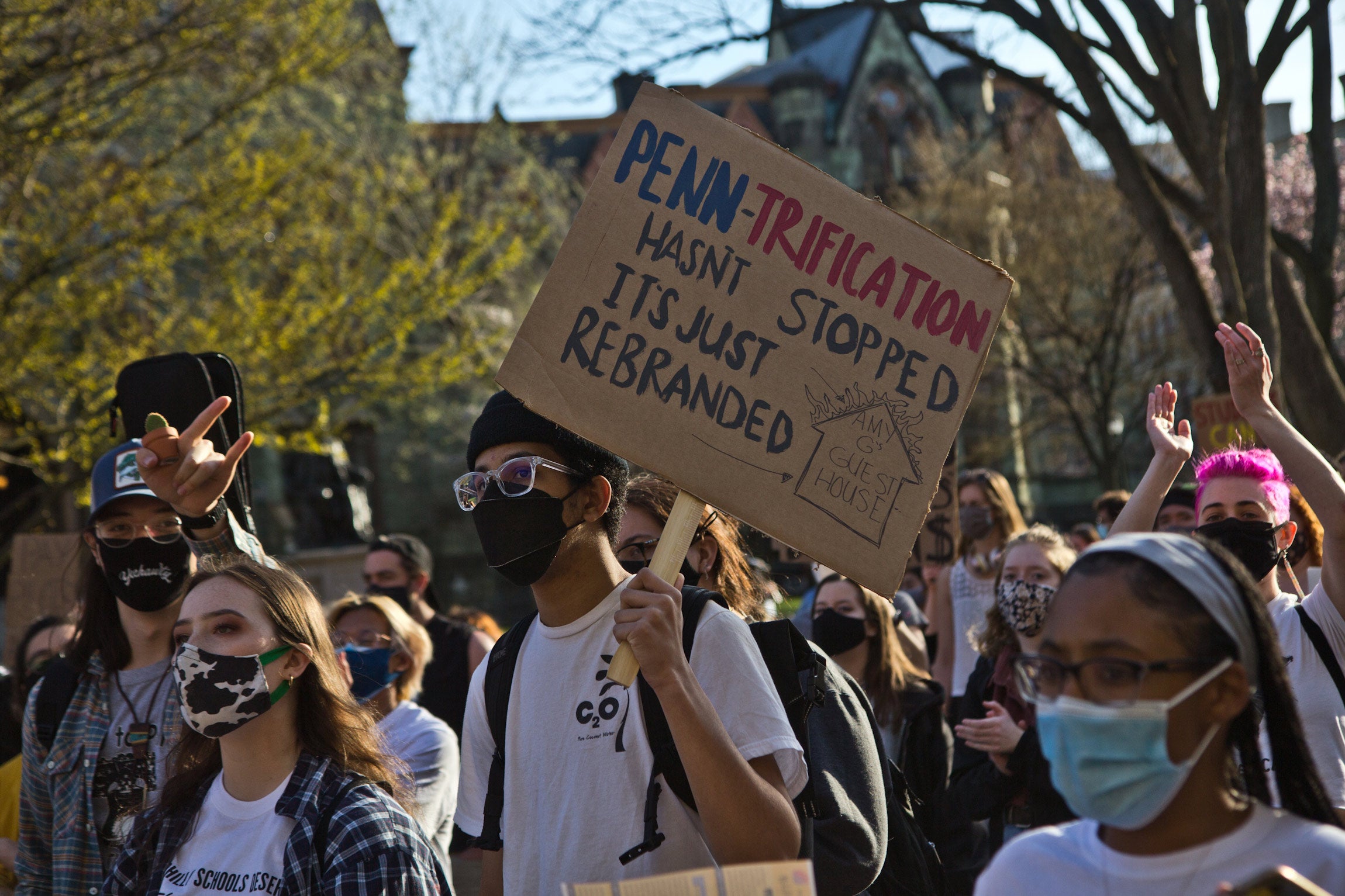

Protesters again push Drexel, Penn to pay PILOTs to Philly public schools

Activists, including students, teachers, and community members, want the universities to contribute 40% of the property taxes they don't pay to the district.

Protesters march on the campus of the University of Pennsylvania demanding the school and Drexel University pay PILOTS to support Philadelphia schools on March 30, 2021. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Over 100 students, teachers, and community members marched through Drexel and the University of Pennsylvania’s campuses on Tuesday evening calling on both schools to make payments in lieu of taxes to support the School District of Philadelphia.

A drumline led the protesters through the streets, organized by advocates from Philadelphia Jobs With Justice, the Our City Our Schools Coalition, Penn for PILOTs, Home and Schools Association, Caucus of Working Educators, Juntos, and other groups. Backed by the percussive sounds and passing many cheering onlookers, marchers chanted, “Penn, Penn you can’t hide, we can see your greedy side.”

Pennsylvania does not require nonprofits, including colleges and universities with large endowments, to pay property taxes, but Philadelphia advocates have been pushing for these payments, known as PILOTs, since at least November 2019. Now, they’re explicitly asking the universities to contribute 40% of the property taxes they don’t pay to the district. The group did not have an estimate for how much that would yield for the city’s schools.

Last fall, Penn pledged a $100 million donation to be paid over the next 10 years to help fix infrastructure problems in schools, such as asbestos and mold. Penn Media Relations Director Ron Ozio also pointed to the university’s history of community engagement initiatives, its hiring of area residents, and purchasing from local businesses.

But Devan Spear, a West Philadelphia resident and the executive director of Philadelphia Jobs With Justice, said that is not enough. She said the $100 million donation “doesn’t account for how steadily their endowment and property portfolio has been growing over the past 10 years.”

Penn owns an estimated $3.2 billion in property in the city.

Advocates say they also fear the university will not hold itself accountable throughout the 10 years.

“Our role as community members and stakeholders is to play the watchdog when it comes to how Penn is following through on this pledge,” Spear said.

Organizers said Thursday evening’s march was also meant to pressure Drexel to take action. The protesters were unsatisfied with Drexel’s response to Penn’s pledge and the call for PILOTs.

“We want Drexel to come to the table,” Spear said.

In response to Penn’s announcement last November, Drexel President John Fry released a statement pointing to the university’s contributions to two West Philadelphia schools, Samuel Powel Elementary and the Science Leadership Academy Middle School.

Drexel responded to a request for comment by sharing an online Q & A in which the university’s Senior Vice President of Government and Community Relations Brian Keech said that the PILOT initiative is based on a lack of information about the school’s history of community contributions and misunderstanding of nonprofits like Drexel’s role in civic life.

“Cherry-picking just a few schools to support,” said Spear, is not actually “going to make a lasting systemic difference for students in the public school system.”

Rick Krajewski, a Pennsylvania state representative for Southwest Philadelphia and a Penn alumnus, said the university’s pledge is only one step of many toward building equitable education access in the city.

“An institution with $14 billion in endowments can do so much more. It must do so much more,” Krajewski said. “We can model what it looks like to create real community benefit agreements between a university and a neighborhood it aims to serve.”

For Christina Ly, a youth organizer with VietLead and a senior at the Academy at Palumbo High School, plans to attend Penn this fall, and said PILOT agreements would result in safer schools for all students in the district.

In 2018, Ly experienced a catastrophe at Palumbo. Heavy rains caused the school to flood and part of the cafeteria ceiling collapsed. Students dodged buckets of rainwater in the hallways to get to class.

The cafeteria was flooded, so students were forced to eat lunch in the gymnasium — an area with documented issues of lead paint residue and damaged asbestos — before an early dismissal.

These are not uncommon experiences in district schools, which have long been plagued by infrastructure problems and billions of dollars in deferred maintenance. Philadelphia teachers and community members have also pointed to those issues in their calls to slow down plans to return to in-person learning amid the pandemic.

Ly also said schools need funding for full-time support services, including nurses, psychologists, mediators, special education teachers, English as a Second Language teachers, and more.

“Instead of all those positions, we’re given more police,” said Ly, adding that policing in schools disproportionately impacts students of color.

“Schools being underfunded are prolonging anti-Black and anti-Asian violence,” she said, “and if Penn, Drexel, and other mega nonprofits really want to address this, then they must pay their fair share.”

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.