‘We’re in competition with the couch’: Philadelphia theater plots its future

The pandemic fundamentally changed how audiences go to live theater. Now local companies are banding together to face the future.

Listen 3:31

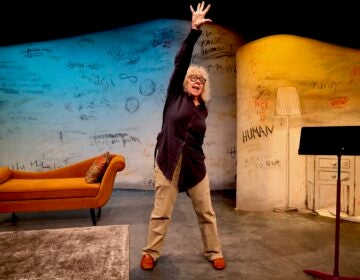

The cast of Shakespeare in Clark Park's ''Two Gentlemen of Verona'' perform the opening number of the 1971 rock musical version of the play. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

The annual free performance of Shakespeare in Clark Park returns this week with the 1971 rock musical version of “Two Gentlemen of Verona,” which authors John Guare and Mel Shapiro based on the Shakespeare comedy.

Director Shamus McCarty leans into the musical’s roots, draping the performance in 1970s style.

“It’s like a full-on ’70s fantasy,” he said. “Nods to disco. We’ve got mylar curtains. Lots of fun, silky fabrics.”

McCarty also leans into the original play’s cross-dressing hijinks, as two women travel abroad disguised as men in order to search for their beloveds.

“In a country where gender expression is being actively attacked in legislation and in the public space, I think one of the ways we can fight that is to unapologetically present it as a norm, and as a thing to be celebrated,” McCarty said.

Visitors to Shakespeare in Clark Park outdoor production should not expect the scale of the 1971 Broadway show that won two Tony Awards, nor even the scale of previous Shakespeare in Clark Park productions they might have become familiar with.

Gone are the large-scale sets that once recreated an entire village or a crash-landed spaceship. Gone are the dozens of extras that used to fill the acreage of the park, the non-professional community members that, for example, once staged a fully choreographed battle for “Henry IV.”

“Two Gentlemen of Verona” is partially a concert performance with costumed performers singing on-book, and partially a staged musical with action and choreographed dance routines. There is no live band; the performers sing to pre-recorded music tracks.

McCarty said the production is intentionally scaled back as the company is in a transitional moment. Shakespeare in Clark Park’s longtime artistic director Kittson O’Neill, who spearheaded the company’s so-called Radical Community Engagement efforts, stepped down last year. McCarty has taken over that role as guest artistic director.

And, the money is not there anymore. Shakespeare in Clark Park is always free, so it gets no ticket revenue and relies on donated funds. Like theaters everywhere are experiencing, fewer dollars are coming in and plays cost more.

When the pandemic forcibly shut down theaters in 2020, the entire industry took a step back to consider how it operates. One determination was that cast and crew should be compensated appropriately. McCarty, facing a budget shortfall, decided to pay people what he could and ask them to work less.

“Our industry has seen a lot of people who have changed their own boundaries and parameters around work,” McCarty said. “I think audiences are going to be, like: ‘Oh, this feels different. This feels smaller.’ The reality is we couldn’t pay people more.”

Before the opening performance on Wednesday evening, McCarty made introductory remarks to set the audience’s expectations.

“We did this entire thing in about 30 hours of rehearsal,” he said. “So it looks a little bit different than Shakespeare in Clark Park has in the past.”

Shakespeare in Clark Park is not alone. Companies across the country are struggling to survive since the pandemic shutdown dealt a killing blow to the theater industry. In Philadelphia, theater companies are changing the way they operate to adjust to audiences who have not returned since the pandemic, and contributed funds are getting scarce.

KC MacMillan, artistic director of two small companies, Tiny Dynamite and Inis Nua, said the wave of donations spurred by the pandemic in 2020 and 2021 is largely over.

“My fear then was, ‘Great, we’re doing okay now, but they’re going to get tired,” she said. “They’re going to say, ‘I gave my money and that problem’s solved and I am moving on.’ And that is what we are seeing. I am seeing fatigue on the part of even our most loyal donors, that we’re in an economy that feels less certain for them.”

The audience’s ticket-buying habits became less predictable even before the pandemic, which only heightened that uncertainty. Fewer people now buy season subscriptions, and more people are waiting until the day of a performance to purchase their tickets.

MacMillan is leaning into audience behaviors by staging fewer mainstage productions at the Drake Theatre on Hicks Street, and more pop-up performances in the relaxed atmosphere of the Fergie’s Pub upstairs room, in Center City. Even with a hit on her hands, as MacMillan had last season with the play “10 Dates with Mad Mary,” by Yasmin Akram, it was difficult to leverage that buzz into ticket sales.

“There was a time when a show would get a great review and the phone would ring. The phone would ring all day. Then you knew pretty early on in the run this is going to be a hit. Let’s take the time, make sure we can extend, run the numbers, and do it,” MacMillan said. “But if you’re having people buy tickets on Saturday afternoon for Saturday night, even if it’s going well and people leave happy you still don’t know if people are going to show up.”

MacMillan plans to restage “10 Dates” this fall during the upcoming Philly Fringe Festival, hoping people will remember the play.

Theater companies large and small are abandoning the idea of announcing an entire season of productions or selling tickets in advance. Last year People’s Light and Theatre in Malvern programmed its season as two sets of series, a fall/winter and a spring/summer, not announcing or selling tickets until just a few months or even weeks beforehand.

Managing director Erica Ezold said the new programming model gives the company flexibility.

“It allows us not to be fully committed to all of the shows in the second half of our season,” she said. “So if something came up that we felt would be a better fit, with a title that would speak to the current moment, we could be more responsive.”

The People’s Light subscriber base has dropped by two-thirds since the pandemic, going from 3,000 in 2019 to 1,000 today. Subscribers now represent about 25% of total ticket revenue. With more last-minute ticket buyers, the company has shifted to focus less on tracking subscribers and more on what Ezold calls stakeholders — people inclined to attend some events at People’s Light, but not go to everything.

“You’re not somebody saying from the outset, ‘I’m going to come seven, eight times a year to People’s Light, I’m going to see all the shows,’” she said. “You’re saying, ‘There might be three shows that I want to see, and I’m really excited by this one-off event.’ So it’s giving you the flexibility to pick and choose what things on the People’s Light campus you want to be a part of.”

While another Philadelphia theater company, Simpatico, is much smaller than People’s Light, it has similarly let go of programming a season in advance, only staging plays when they are ready, with little lead time. Last year it produced just one play, Charlie DelMarcelle’s “The Shadow the Broke the Light,” about the familial cost of addiction. Speaking directly to Philadelphia’s opioid epidemic, it got positive reviews and drew sold-out crowds.

“We often have a number of plays in development at any given time,” said artistic director Allison Heishman, in an email. “Choosing the piece that speaks most directly to what is important to our community is one of our core values.”

Realizing they are all treading water in the same tide, many of Philadelphia’s theater companies have started banding together to find collective solutions. Earlier this week, 27 leaders representing 16 theater companies convened at the Arden Theatre for an open discussion about the state of theater in the region, and an increasingly wary audience.

One of the coordinators of the meeting, Arden co-founder Terry Nolen, said it was an informal gathering to encourage companies to share information with one another.

“When we look at the news nationally of theaters that are closing, significantly downsizing, suspending programming, we wanted to talk with our peers here in Philly to see what exactly people are experiencing,” Nolen said. “Where are we actually at? How much work are we providing? What are we paying? Let’s gather the data so we know what we’ve lost and we know how we’re going to move forward.”

Ezold, of People’s Light, said one of the biggest concerns across all theater companies is that audiences have fallen out of the habit of going out to see a show.

“We’re in competition with the couch. We’re not in competition with each other,” Ezold said. “I think our biggest challenge is reminding people what it is to sit in a theater, what that feels like. Because I think people have forgotten.”

But Nolen at the Arden is optimistic that theater may have turned a corner. Last season, about 70,000 people came to the Arden to see a show. After a slow start in the fall with weak ticket sales, the vast majority of his audience — about 50,000 — came in the last six months of the season.

While overall season subscriptions are down, Nolen said 87% of his subscribers have re-subscribed, a higher renewal rate than typical pre-pandemic seasons. He programmed the next season with large-scale productions like the Steven Sondheim musical “Assassins,” and “The Lehman Trilogy,” an epic play lasting 3 ½ hours, spanning two centuries.

“Yes, we’re doing two less productions,” Nolen said. “But the seven shows we are doing, we’re bringing everything we can. We want to hire as many artists as we can, and run the shows and extend the shows as often as we can. That’s part of spreading the word that Philly theater is worth investing in and is worth supporting.”

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.