John Dougherty and Bobby Henon convicted of conspiracy in federal corruption trial

A jury found City Councilmember Bobby Henon and union boss John “Johnny Doc” Dougherty guilty on most counts in the federal corruption case against them.

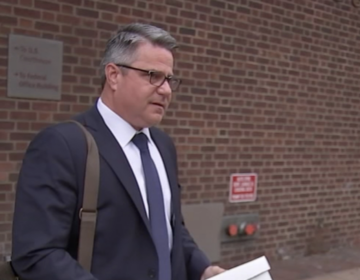

Philadelphia City Council member Bobby Henon walks to the federal courthouse in Philadelphia, Wednesday, Nov. 10, 2021. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

A jury has found City Councilmember Bobby Henon and electricians union boss John “Johnny Doc” Dougherty guilty on the majority of counts in the federal corruption case against them, giving U.S. Justice Department investigators and prosecutors a win in their more than decade-long effort to put the powerful labor leader behind bars.

Dougherty was convicted of eight of the 11 charges he faced, and Henon 10 of 18 counts. The jury found both men guilty of conspiracy and honest services fraud and Henon guilty of bribery. They acquitted Dougherty on three additional counts of honest services fraud and acquitted Henon on eight additional counts, including honest services fraud and federal program bribery.

The verdict announced Monday afternoon comes more than six years after the FBI began secretly wiretapping phones belonging to Henon and Dougherty, and five years after the federal investigation exploded into public view with early-morning raids on their offices and Dougherty’s home.

Henon and Dougherty remained expressionless as the verdict was announced and those assembled in the packed courtroom were quiet as the jury foreman read off the verdict sheet.

Prosecutor Frank Costello argued that Dougherty’s bail should be revoked and he should be immediately jailed. He said the union leader posed a danger to the community, and played a phone call from 2016 in which Dougherty described having just punched a man in the street in a dispute over a union sticker on a truck, breaking the man’s nose.

But U.S. District Judge Jeffrey Schmehl denied the request, saying the incident occurred too long ago to merit locking Dougherty up now.

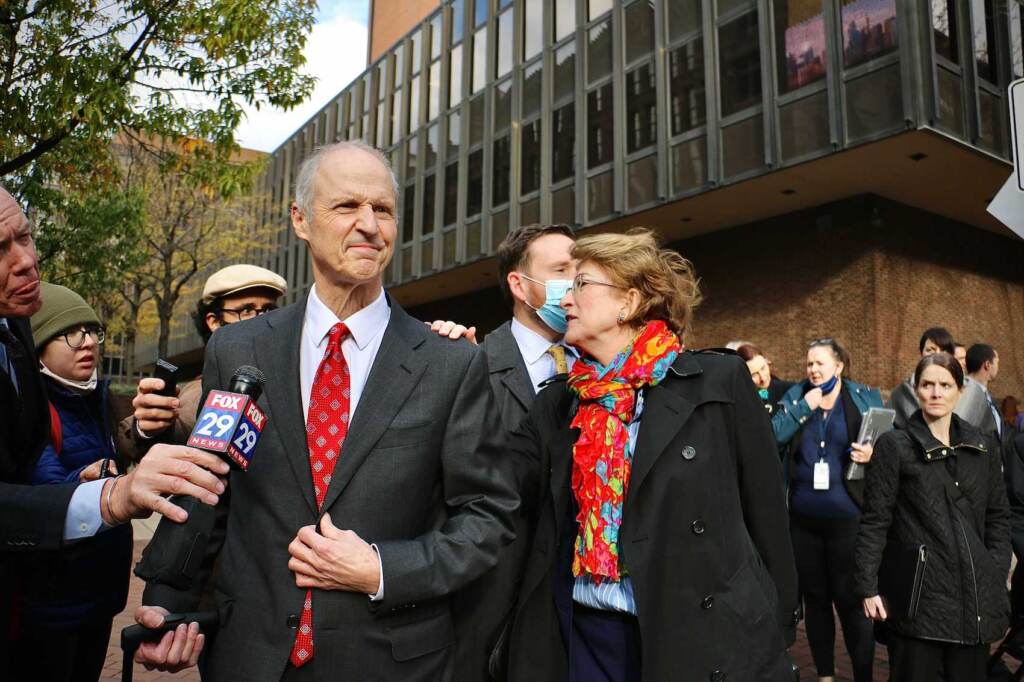

The two men each face up to 20 years in jail for the most serious of the charges, although they can argue for shorter terms and will appeal their convictions. Henon will have to give up his council seat and government pension when they are sentenced at hearings scheduled for late February.

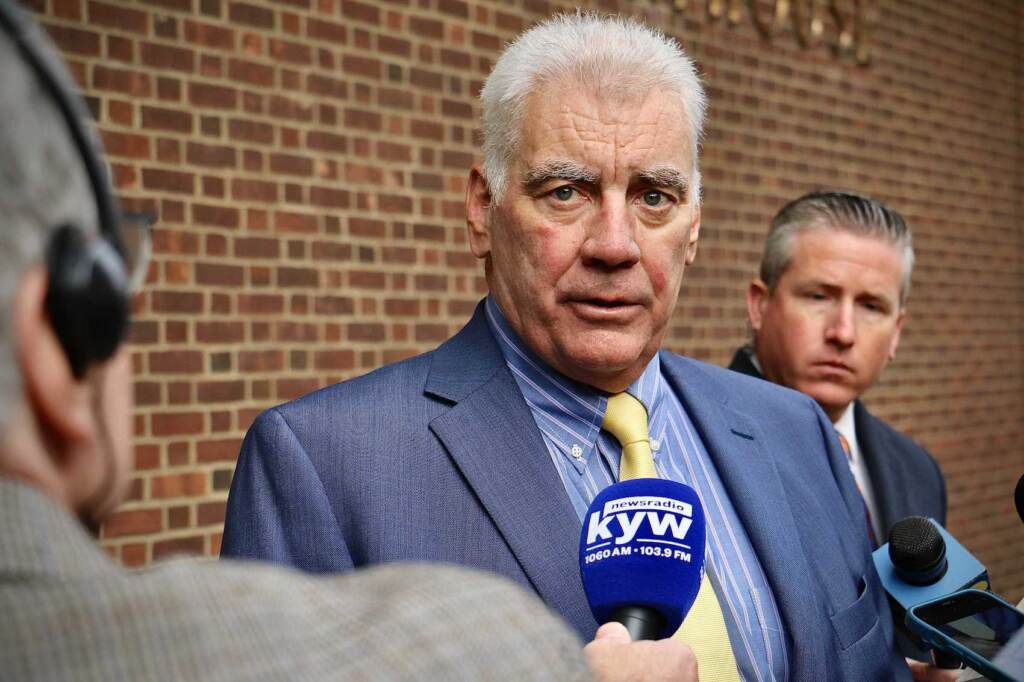

“Justice was not served today, and I can’t tell you how disappointed I am by the jury’s decision,” Dougherty said in a statement Monday afternoon. “What Councilman Henon and I were found guilty of is how business and politics are typically and properly conducted. I will immediately appeal and have every confidence that I will prevail in the Third Circuit Court of Appeals.”

The jury agreed with prosecutors’ contention that Dougherty, business manager at Local 98 of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers since 1993, bribed Henon in 2015 and 2016 with a $70,000 salary and benefits for a no-show union job. The bribe also included nearly $20,000 worth of tickets to Philadelphia Eagles games and other sporting events.

In return, Henon served as a council member on retainer to Dougherty, helping him attack his rivals in other unions and pressure large employers to hire union electricians, prosecutors said.

Henon also was offered or took bribes from two other sources, former Philadelphia Parking Authority board chair Joseph Ashdale and James Gardler, president of Communication Workers of America Local 13000.

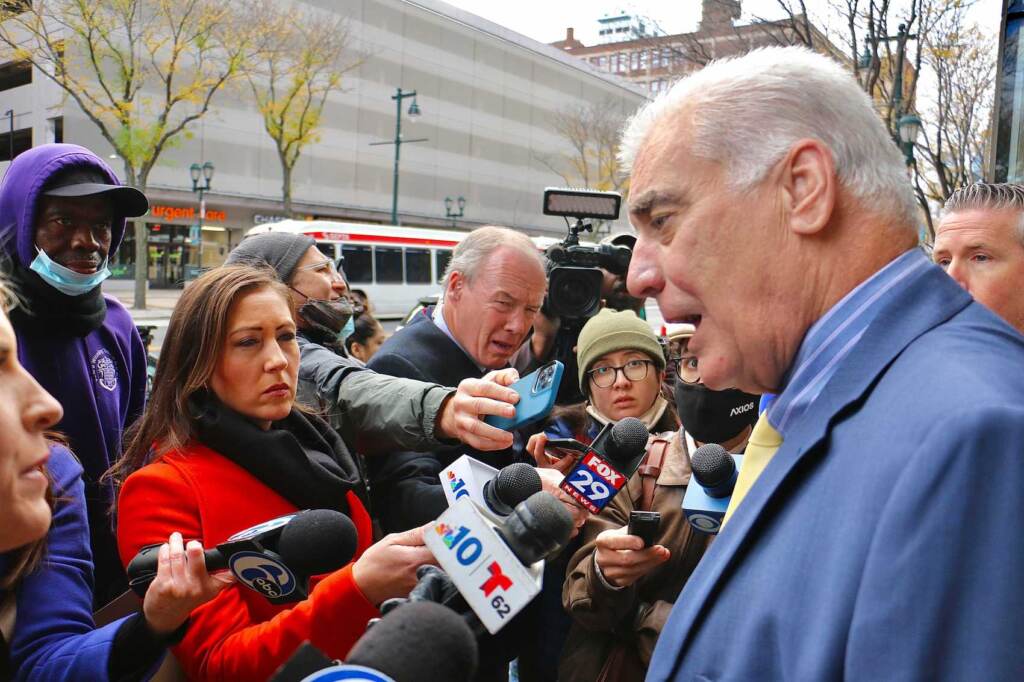

“Today’s verdict is a strong message to the political power players of this city, and any city, that the citizens of Philadelphia will not tolerate public corruption as ‘business as usual,’” said Jennifer Arbittier Williams, Acting U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, at a press conference outside the courthouse.

Dougherty “had no right to pull the strings of official city business as if he were elected to office,” she said. “And Bobby Henon was not elected to represent Local 98 or John Dougherty’s interests on City Council, or any union for that matter, but to represent all of the people of the city’s 6th Councilmanic District, a fact which he failed to remember in doing the bidding of his political godfather, John Dougherty.”

The indictment of the two men in 2019 upended the political scene in Philadelphia, where Dougherty was long considered one of the city’s most powerful unelected officials. His union is the state’s single biggest independent source of campaign funding, typically donating more than $2 million a year to political candidates and committees. The majority has supported Democrats, including his brother, state Supreme Court Justice Kevin Dougherty.

Henon, a former electrician, ran for City Council in 2011 with support from the union and represented the 6th District in Northeast Philadelphia for nearly a decade. Before that, the father of two served as Local 98’s political director for eight years.

Struggling with a ‘dual role’

The prosecution’s case relied heavily on dozens of often profanity-laced phone calls recorded between May 2015 and September 2016, in which the two men strategized about how Henon should use his positions as a councilmember and, eventually, Majority Leader to further Dougherty’s goals.

The calls showed the Local 98 boss apparently instructing Henon to draft legislation, arrange private meetings, call hearings, and vote for or against bills in council. The union leader described Henon as his man “on the inside,” and on at least one occasion expressed displeasure when the council member was not delivering on his priorities.

“What you’re doing is right by what you got to do for the city … but none of our issues were addressed,” he complained to Henon in November 2015, in reference to a major piece of legislation renewing Comcast’s cable TV franchise in the city. “I only care about the couple things that were … excluded.”

In that instance, Henon was unable to add Dougherty’s demands to the bill, but he arranged private meetings in which the union leader allegedly told Comcast executives he would hold up the legislation if the company did not agree to hire more union workers.

The councilmember subsequently described to Local 98 political director Marita Crawford the “unbelievable amount of stress” he felt as he tried to simultaneously satisfy Dougherty and shepherd the Comcast bill through City Council.

“[Henon’s] like, ‘you don’t know what it’s like on the inside,’” Crawford later reported to Dougherty. “I said, yes, I do … I said, ‘you want to be on the outside and the inside. If you want to be on the outside and you want to get everything you get from John, then you gotta learn that your role has a dual role’.”

Attorneys for Dougherty and Henon unsuccessfully sought to have the case dismissed, arguing that prosecutors had not produced evidence of a quid pro quo — an explicit agreement in which both defendants agreed to an exchange of official council actions for bribes.

Schmehl did agree to toss out one count against Dougherty relating to a bribe Henon was offered by Ashdale. Dougherty was only minimally involved in that matter.

The defense attorneys, Henry Hockeimer Jr., for Dougherty and Brian McMonagle for Henon, maintained that prosecutors had not proved there was a bribe in the case at all.

They repeatedly pointed out that council members may legally have outside jobs and that several members have incomes from sources other than their council seats. McMonagle argued that Henon’s half-time Local 98 position was not a no-show job, as he actually worked as a kind of unofficial political consultant for the union and representative at meetings of other labor organizations such as the Philadelphia Council AFL-CIO.

The attorneys said Henon collaborated with Dougherty to further the interests of his union member constituents because the two men were close friends and “brothers” with a shared, fervent belief in labor, not because he was bribed.

“At the end of the day, what this case is about is a labor leader supposedly bribing a pro-labor city council member to advance the interests of labor. There’s no bribe under that rubric,” Hockeimer said.

Unions are unusually influential in Philadelphia compared to other cities, and city officials wanted Dougherty on their side as they worked pass broadly beneficial legislation like the soda tax, which funds park and library renovations, pre-K programs, and community schools, Hockeimer argued.

Demands small and large

The wiretaps provided a window on Dougherty’s constant communications with a who’s who of Philadelphia political figures. Mayor Jim Kenney, a longtime close ally of Dougherty, chatted with the union leader about a proposed update to the city’s plumbing code in one recorded conversation, and was frequently mentioned on other calls.

In one call, Dougherty recounted a conversation in which then-mayor Michael Nutter urged him to stop blocking the Comcast bill, and in another he told Henon that former mayor John Street would attend a football game at Local 98’s expense.

Council President Darrell Clarke was heard cursing and commiserating with Henon about Councilmember David Oh’s call for an audit of the parking authority. Councilmember Helen Gym asked Henon whether she needed to note on a financial disclosure form that Local 98 had given her a ticket to an Eagles game. (He erroneously told her she did not.) Hockeimer quoted messages from former mayor and governor Edward Rendell and several other people requesting Dougherty’s advice.

The evidence presented by Assistant U.S. Attorneys Richard Barrett, Frank Costello, and Bea Witzleben also included text messages, emails, fundraising letters, financial records, photographs, and videos of City Council hearings. Over five weeks of testimony, the jury often heard from the prosecution’s main witness, FBI Special Agent Jason Blake, along with 52 other people.

They included many character witnesses who described Henon’s work on behalf of families during the pandemic, children’s recreation programs, police officers shot in the line of duty, and a Black church battling racially-tinged opposition to a building project, among other causes.

Courtney Voss, Henon’s chief of staff with whom he was having an affair, gave emotional testimony in which she defended him as a passionately pro-labor public servant who at one point in the pandemic was providing groceries for 800 Northeast Philadelphia families in need.

“Bobby isn’t just a supporter of labor,” she said, quoting one of his campaign slogans. “He is labor.”

Voss described how Henon helped her during her financially calamitous attempt to renovate a historic home in 2015 and 2016. That effort that led him to solicit a bribe of window glass for the home from Ashdale, who heads a glaziers (window installers) union in addition to formerly chairing the PPA board.

The corrupt acts the council member undertook ranged from the almost trivial — agreeing to call a hearing on towing companies after Dougherty angrily complained about his car being towed, but then never following through — to weighty actions like holding up the renewal of the Comcast franchise, a deal worth tens of millions of dollars in city tax revenue.

The council member aided Dougherty’s personal ambitions, threatening to schedule hearings on a city plumbing code update in order to pressure the plumbers union, who opposed Dougherty’s bid to head the Philadelphia Building & Construction Trades Council, an umbrella group of unions.

Prosecutors said Henon supported the city’s controversial soda tax in 2016 in part to retaliate against the Teamsters union, which includes beverage truck drivers.

The Teamsters had tangled with Dougherty over a union picket of the Pennsylvania Convention Center, declined to endorse Kevin Dougherty in his primary run for Supreme Court, and ran a television commercial that criticized the Local 98 leader. Defense attorneys responded by showing that Henon’s staff had started working on new soda tax proposal months before he and John Dougherty talked about the Teamsters.

On two occasions, Henon helped Dougherty get the Departments of Licenses & Inspection to issue stop-work orders on the installation of MRI machines at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Dougherty told Henon to call Carlton Williams, the L&I commissioner at the time, because the work was being done by out-of-state, non-union workers.

Henon also was offered or took bribes from two other sources. One was Ashdale, an old friend who asked Henon to vote against Oh’s bill requesting an audit of the PPA and promised to cover the cost of Voss’s window glass. After the FBI raids revealed Henon was under federal investigation, Ashdale ended up refusing to pay for the windows.

The other briber was Gardler, president of CWA Local 13000, who gave Henon $13,000 in campaign contributions in exchange for holding a hearing that created negative publicity for Verizon. CWA was on strike against the company at the time. Neither Ashdale nor Gardler were charged.

More trials to come

The U.S. Justice Department has been targeting Dougherty for at least 15 years. An investigation in 2006 ended without him being charged but resulted in the indictment of a friend with the same last name, Donald Dougherty, who pleaded guilty to theft, tax evasion, and making false statements.

In addition to Monday’s convictions, the current federal investigation has previously produced a guilty plea from George Peltz, a childhood friend of John Dougherty’s and owner of the Berlin, New Jersey-based MJK Electric. In 2019, Peltz pleaded guilty to four criminal counts, including tax evasion, theft of union funds, and unlawful payments to Dougherty, to whom he provided $57,000 in home and office improvements at no charge between 2012 and 2015.

Dougherty pressured Comcast to steer work to MJK, according to testimony during the current trial. MJK charged rates up to 10 times higher than Comcast’s standard rates, and over the next three years was paid more than $9 million for projects that included wiring the Wells Fargo Center for the 2016 Democratic National Convention.

The case decided Monday is the first of three simultaneous criminal prosecutions involving Dougherty. It was originally part of a 116-count grand jury indictment brought in 2019 against him, Henon, and six others affiliated with Local 98, which Schmehl later split into two trials.

The other half of the indictment alleges that Dougherty and the six others embezzled $600,000 from Local 98 to pay for groceries, restaurant dinners, and personal travel. A start date for that trial has not yet been set.

An additional, 19-count federal indictment in March charged Dougherty and his nephew Gregory Fiocca with conspiracy and extortion for allegedly threatening “violence and economic harm” on a contractor if he did not continue employing and paying Fiocca, even for hours he didn’t work.

And in yet another federal case, the U.S. Department of Labor in January filed a civil suit to remove Dougherty and a slate of other union executives from their posts at Local 98. They are accused of intimidating and threatening other members who tried to challenge them during the union’s June 2020 election.

Initially scheduled to start in September 2020, the trial was repeatedly postponed, due in part to a pandemic-related backlog in the federal courts. The start of jury deliberations was delayed last week for a day after a juror tested positive for COVID-19 and was excused from the trial. The remaining jurors all tested negative.

Disclosure: The Electricians Union Local 98 represents engineers, camera personnel, editors, audio and maintenance techs at WHYY.

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.