Checking in, not out: How libraries are moving from closed toward reopening

There’s no single blueprint for making these public spaces public again, no agreed-on best practices for sanitizing materials. Libraries learn as they go.

Free Library of Philadelphia (Miguel Martinez/Billy Penn)

Are you on the front lines of the coronavirus? Help us report on the pandemic.

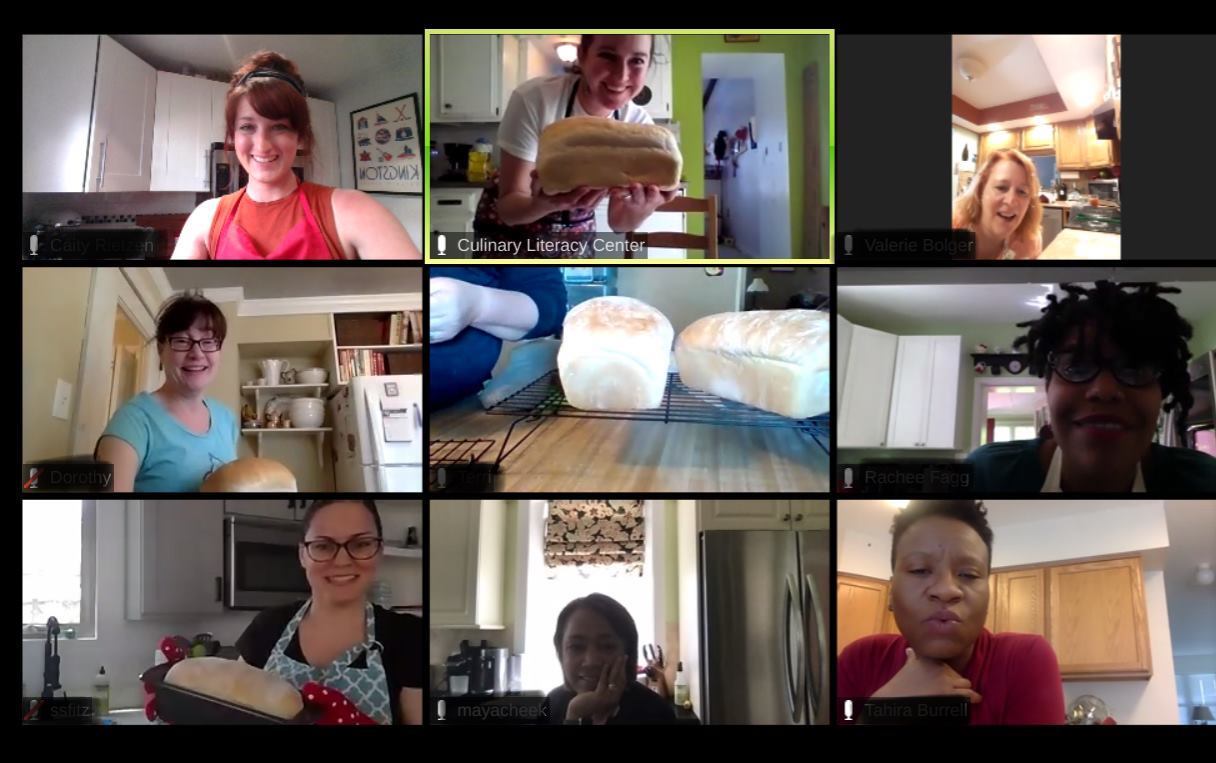

Liz Fitzgerald is an administrative librarian with the Free Library of Philadelphia. A few months ago, her typical day would have involved spending time with dozens of people: sitting around a table to plan activities in the learning center, or running into the kitchen to taste food prepared by a group of curious kindergartners. Her team organized as many as 30 events a month.

And then, in a matter of days, all that changed. Her days now mostly involve sitting in front of a laptop.

“The fact that we closed three months ago seems crazy,” Fitzgerald said.

The Library of Congress closed all of its buildings and facilities to the public at 5 p.m. Thursday, March 12. Only 24 hours later, Philadelphia’s Free Library system did the same. That makes it a little more than three months that these facilities have been shuttered, the longest Pennsylvania’s libraries have ever been closed.

When they packed up their things in mid-March, Fitzgerald said, and her staff “anticipated being closed for a while” because of the coronavirus, but they didn’t really comprehend what that meant.

“We were contacting our partners … [trying] to get as many in-person meetings as possible, gathering our plants, heading out the door,” she recalled. “I think we all wished that we gave more hugs goodbye.”

What’s the plan for saying “hello” again and making these very public spaces public once more?

There is no publicized reopening strategy yet, according to city officials and library staff. Philadelphia entered the “yellow” phase of reopening from the state-mandated shutdown on June 5, and currently all 55 branches of the city’s Free Library system remain closed. Deana Gamble, communications director for Mayor Jim Kenney’s office, said libraries won’t reopen until at least the “green” phase of the governor’s plan.

As they weigh when, and how, that can occur, library staffers must take a variety of things into consideration: state restrictions; individual county health department recommendations; new OSHA guidance around COVID-19; and the Pennsylvania Department of Education’s Office of Commonwealth Libraries’ Framework for Reopening Public Libraries, among others.

In the meantime, the roadmaps other libraries have followed offer examples of what the Philadelphia system’s continued closure, and eventual reopening, could look like.

On the books already

In Allegheny County, which moved to the ”yellow” phase May 15 and on to “green” June 5, Pittsburgh-based Carnegie Library staff have been working cautiously toward a return to service. On Monday, the library hosted a one-day book return event. By June 23, it plans to extend curbside service to five locations, although its actual buildings still won’t be open to the public.

Suzanne Thinnes, a representative of Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Library system, is careful to stress that the library itself never really closed.

“Since the pandemic forced us to shut down our buildings, we have been providing services remotely and virtually,” she said. At the beginning, staff members were offering online events and working to ensure library users knew about the e-resource collection. Over time, services have expanded to include one-on-one resume and job application review sessions, mock interviews, and more. Still, all of Carnegie Library Pittsburgh’s in-building programming is suspended through August. That could be extended, Thinnes said, depending on Gov. Tom Wolf’s recommendations.

Over in New Jersey, libraries have been closed since March 21, but Gov. Phil Murphy recently announced that he would allow them to offer curbside pickup starting this past Monday.

In Delaware, libraries — which are categorized alongside art galleries, museums and performing arts centers as part of the arts and culture industry — at first opened to in-person functions, although limited to 30% capacity indoors. That restriction expanded to 60% capacity under the state’s second phase of reopening on Monday.

The disparity in reopening approaches speaks to the fact that there is no single blueprint for public libraries, which by their nature are meant to invite a range of users. There isn’t even a historical precedent to copy.

“We have librarians who looked into the Spanish flu back in the early 1900s, and the libraries … did close, but I believe it was for several weeks … it wasn’t for this long,” Thinnes said. “There is no rulebook or guidebook for this type of pandemic.”

At the same time, she added, “it’s been really helpful to talk with other libraries and see what they’re doing, go through their format, see what works and doesn’t work … [We’re] doing a lot of discussion and a lot of research.”

Put on hold: ‘The situation is unprecedented’

One group facilitating reopening discussions is the Urban Libraries Council, a Washington, D.C.-based network of more than 150 North American library systems. The council conducts regular calls for more than 200 individuals every week — and reopening has remained a common thread in conversation.

“I will say that libraries have stayed open during riots, libraries have stayed open during severe weather events. Certainly, library buildings have had to close for those and other reasons before, but libraries are welcoming and inclusive spaces that at its core are dedicated to serving the community,” Curtis Rogers, an Urban Libraries Council representative, told WHYY News. “Certainly, the scale of this is unprecedented, and the situation is unprecedented.”

He pointed to a number of ways public libraries have stepped up as community spaces during the coronavirus crisis.

“There’s library spaces that have turned into temporary food banks, into temporary homeless shelters, there’s libraries among our members that have turned into temporary police stations,” Rogers said.

In Philadelphia, public libraries have served as polling places or ballot drop-off locations long before the pandemic. Nationally, they’ve partnered with government or nonprofit organizations to distribute diapers, meals, educational materials or WiFi hot spots.

Libraries are community spaces, and their reopening strategies need to be community-specific. That’s difficult for Glenn Miller, Pennsylvania’s deputy secretary of the Office of Commonwealth Libraries, as he and his office issue reopening frameworks that need to apply to libraries in tiny towns, as well as those in large urban settings.

“We tried very carefully to develop a framework that could be agile enough to work in any circumstance, while recognizing at the end of the day, the best and most responsible thing we can do is provide our local library boards with all the information that we believe is credible,” Miller said. “From there, they have to develop their [own] guidance.”

For example, there aren’t currently agreed-upon standards for how long the coronavirus can remain on library materials like books or DVDs, or best practices for disinfecting such materials. So instead of offering specific standards, the state’s recently revised framework — which draws on Centers for Disease Control guidelines, Department of Health standards, and more — offers information about each stage of reopening, with possible considerations as well as links to research and resources.

For counties in the yellow phase, where Philadelphia is now, the framework recommends staffing in staggered shifts, requiring mask and sanitization protocols, establishing traffic patterns and building plastic “sneeze shields” in preparation of return to in-building service, and altering circulation schedules around disinfection and quarantine periods for returned/handled library materials. For counties in the green phase, the framework currently recommends a continuation of those policies, just with higher in-building capacity.

And even as state restrictions start to lift, officials say library staff and users would do well to maintain caution.

“Green doesn’t necessarily mean fling your doors open, business as usual,” Miller said. “Green means cautious services, maintaining social distancing, masking and so forth.”

He said the reopening process across the state has reflected the way the virus has spread, with more caution encouraged in regions where COVID-19 risk is high.

Reading rooms, yes, but more too

In a sense, Miller said, the coronavirus pandemic also “accelerated a move that was already underway.” Online services in libraries have been growing and growing in recent years, he noted, and he expects that digital programming will continue, even after a return to in-person, in-building library service.

“But there is a value to the library as a community space, particularly in a period where we’ve been isolated from one another,” Miller said.

It’s that isolation that Fitzgerald, who serves as the head of the Philadelphia Free Library’s culinary literacy center and language-learning center, feels deeply. She described the programs she oversees — cooking classes, language courses and more — as “not only place-based, but community-based.”

She agreed with Miller that the coronavirus shutdown accelerated a shift toward online programming that might not have occurred otherwise. At the same time, even that online programming can offer a challenge. Nearly 1 in 5 households in Philadelphia don’t have reliable digital access, according to census data.

“That’s something that’s been a big part of our conversations, offering so much online, but being cognizant of the fact that so many Philadelphians are without access to high-speed internet,” Fitzgerald said. “It’s going to be one of the challenges that we continue to try and solve as we reopen.”

It’s also a factor in her drive to reopen. Libraries aren’t just a place to check out books, as any librarian can tell you; they’re also public spaces, public services, information centers, community hubs. For many neighborhood members, they’re a source of critical digital access, Fitzgerald said.

“I think about all of the people who come to the library to print out applications for jobs, to do their tax forms … I think about the people who are really reliant on our computers and our Wi-Fi, and I worry about what they’re doing now.”

In Miller’s words, “public libraries serve the full range of the human experience.” From toddler story hours to senior tech assistance, he said, library services are critical.

“We know that people miss their libraries very badly. We hear that,” Miller said. “But we also know we have to balance that passion for libraries and what they provide to Pennsylvanians with the reality that this virus is still here … We don’t want to do anything that will trigger a second outbreak.”

Show your support for local public media

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)