This painting found in a Glenside thrift store came out of Philly’s 19th-century Black cultural elite

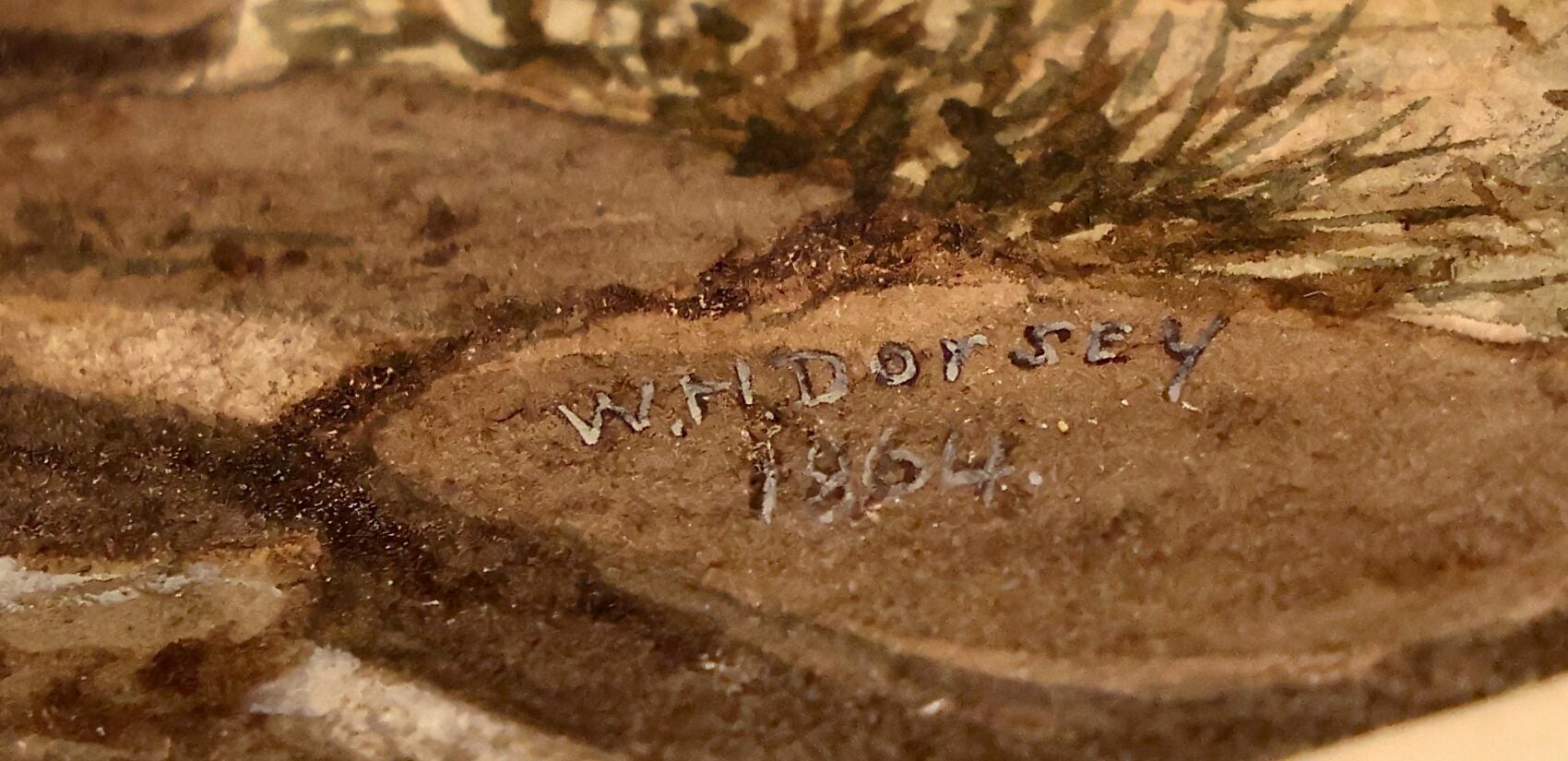

A painting from a thrift store in Glenside is by William H. Dorsey, of Philadelphia’s elite Black society circa 1864.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

A previously lost painting representing 19th-century Black wealth and high culture in Philadelphia is now on view at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania after being bought for $10 at a suburban thrift store.

William H. Dorsey’s untitled watercolor, an oval-shaped landscape dated 1864, is believed to be the only existing painting by the artist from a prominent Black family who once displayed works at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

Dorsey is known as a scrapbooker, collecting and assembling newspaper clippings and ephemera related to the Black community for most of his life. Four hundred scrapbooks are at Penn State as part of the Cheyney University archives.

But David Brigham, director of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, could find no trace of paintings by Dorsey.

“It’s the only one that I’ve been able to find in a museum collection,” he said. “I also surveyed auction records, and I couldn’t find a single work by him.”

Also remarkable: This painting was discovered last year in a thrift store in Glenside, Pennsylvania.

Andy Robbins, who works in human resources for a building materials company, often drops into New Life Thrift on North Easton Road, associated with a Presbyterian church across the street.

“Maybe two or three times a week, usually after work, I’ll stop in here just to kind of unwind,” he said. “A little retail therapy.”

Robbins bypasses the glass figurines, heavy furniture, damaged musical instruments and a full set of fishing waders, making a beeline for what’s new in the records and artwork. He has scored original vinyl pressings of jazz on the Blue Note and Prestige Record labels, and has dozens of original paintings and artist prints culled over the years from thrift stores.

In the summer of 2023 he spied the edge of a frame stored on a shelf with the image facing sideways. It looked old. When he pulled it out, the bucolic picture of a small Black figure fishing next to a church and dilapidated mill piqued his interest.

“It’s a very serene landscape. I like the little guy that was sitting there fishing on the side of the river,” he said. “The tree right next to him was done in these very light brushstrokes that I thought was beautiful.”

Using his phone as a magnifying lens, he deciphered the tiny signature, “W. H Dorsey 1864,” and Googled the name.

“I found out a little bit of information, just enough to make me want to take it away from the store,” Robbins said. “I paid $10 for it.”

Once home, he posted his find on Instagram. In a matter of hours he was contacted by 1838 Black Metropolis, a digital history project of Morgan Lloyd and Michiko Quinones who research and present online stories and walking tours of Philadelphia’s Black community from the mid-19th century.

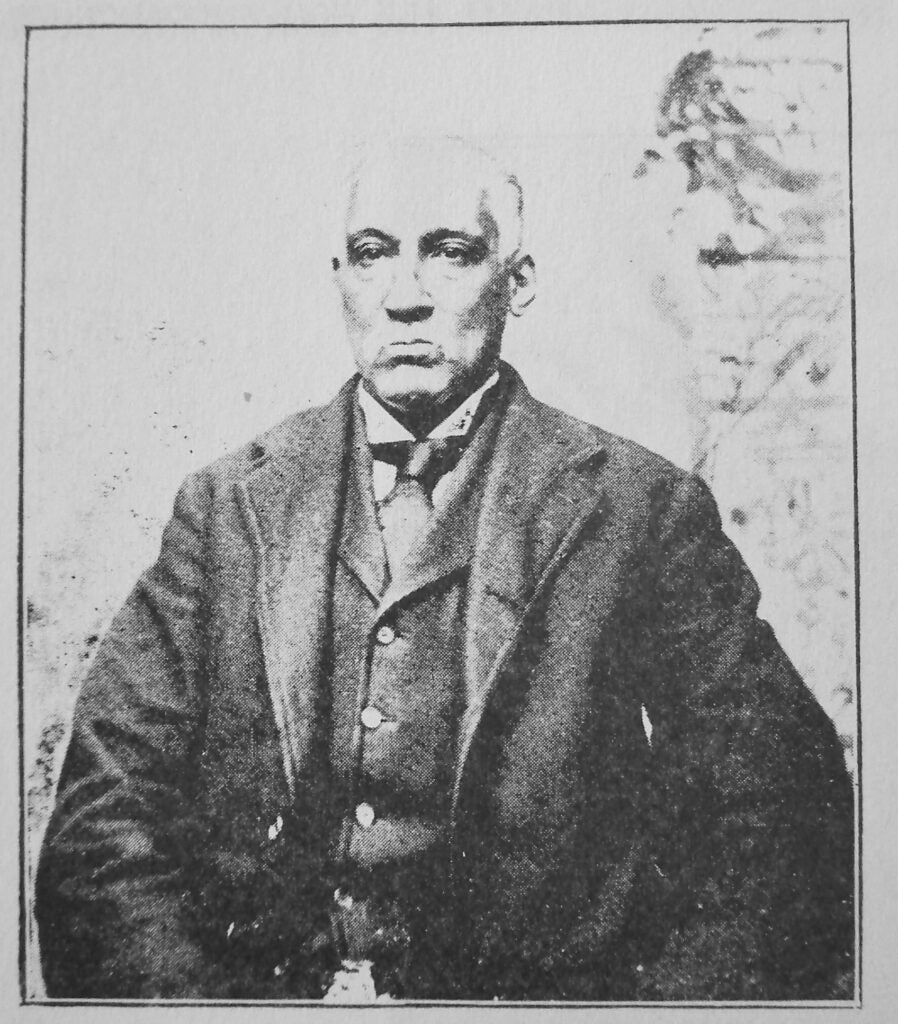

The name Dorsey is well known to Quinones, who has written about William’s father, Thomas Dorsey. He escaped slavery in Maryland with his two brothers in 1836. They came through the Underground Railroad network and landed in Philadelphia, where Thomas started a successful catering business.

An 1896 Philadelphia Times article said the elder Dorsey could “rule the social world through its stomach” and had “the sway of an imperial dictator,” making him a very wealthy man. So much so, his children inherited a life of financial comfort. His son William was able to devote much of his energies to art, history and community work.

William Dorsey co-founded the American Negro Historical Society, which tracked, collected and archived Black history. Among the activities that ANHS followed was baseball, recording game stats of the Philadelphia Pythians, the team co-founded and led by Octavius Catto until his assassination in 1871. Those records are now kept at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Dorsey was also an avid collector, turning two rooms of his house on Dean Street, now South Camac Street, into a museum of African American history and art. That house, which no longer stands, was two blocks from where the Historical Society of Pennsylvania now sits.

“The fact that he was collecting work by Black and white artists speaks to the wealth his family had accumulated,” Brigham said. “To be able to buy paintings by prominent artists was not available to most people, Black or white. The fact that he was filling his home with beautiful things and inviting people to come and see them speaks volumes.”

Dorsey exhibited 11 paintings at PAFA in 1867 and 1868, one of which was titled “The Fisherman,” according to records at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. It is possible that painting is the one discovered at New Life Thrift.

Once Robbins realized he had stumbled onto something of value, he was advised to seek out an appraisal to determine an insurance value. But he never investigated how much the Dorsey paintings might be worth, instead investigating how to donate it.

He reached out to a few museums to test the waters but ultimately took the advice of Quinones and gave it to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

“She thought that it would be a really good place for it to be,” Robbins said. “They have been focusing their acquisitions on this era of Black Philadelphia. Before I found this painting, I knew nothing about it whatsoever. It really opened my eyes to a whole piece of history that I wouldn’t have thought about before.”

The untitled William H. Dorsey painting is on view as part of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s current exhibition of new acquisitions.

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.