‘We feel fiercely’: Kensington finds its poetic voice

After a neon mural of poetry by Kensington residents was completed, the Kensington Healing Verse project continues to guide people into creative writing.

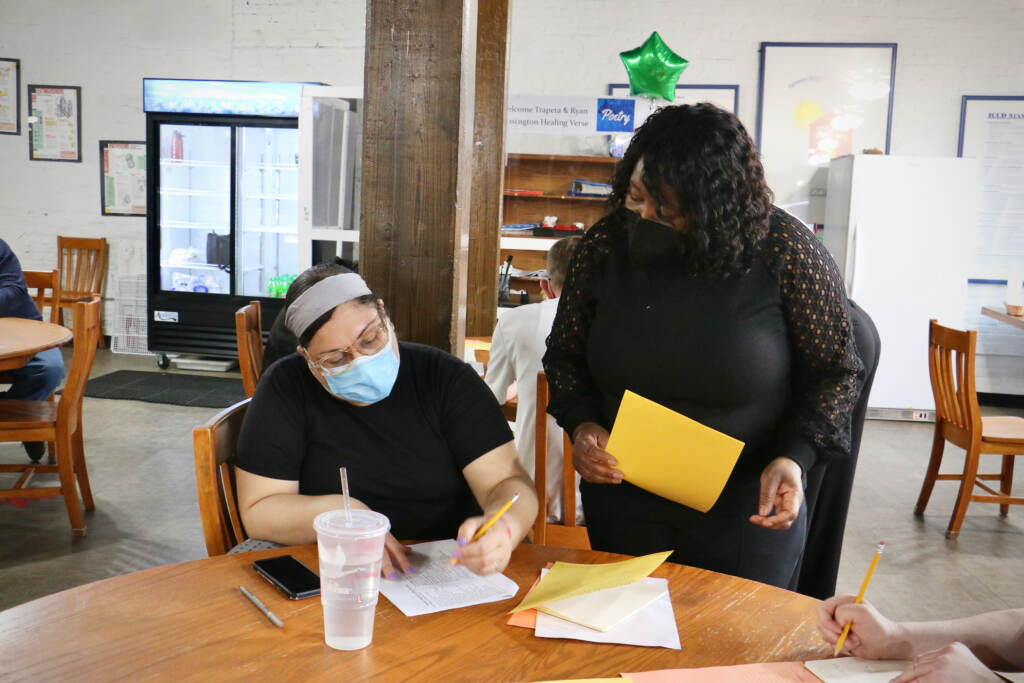

Former Philadelphia Poet Laureate Trapeta Mayson leads a poetry workshop at the Open Door Clubhouse in Kensington. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

In December, a neon billboard went up in Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood, flashing a message of poetic positivity above the corner of York and Front Streets and lighting up the tracks of the York-Dauphin SEPTA station.

“There is always light here,” the sign glows as the evening turns dark.

“We are … shining,” it reads.

Then flickers through a rotation of other words:

“Dazzling.”

“Beautiful.”

“Healed.”

The poem was written collectively by residents of Kensington, projecting their own vision of their neighborhood which has had more than its share of problems.

The mural was a product of Kensington Healing Verse, an ongoing series of writing workshops led by Philadelphia’s former poet laureate, Trapeta Mayson. Kensington Healing Verse is an offshoot of Mayson’s Healing Verse Phone Line, a daily dial-a-poem phone line she developed during her tenure as poet laureate. It continues under the auspices of the arts presenting organization Philadelphia Contemporary.

The neon sign, created through Mural Arts Philadelphia, is one result of Kensington Healing Verse but not the end result. Even after Mural Arts completed the neon sign, Mayson continues to visit locations in Kensington to guide people to express themselves, many of whom have never attempted to write poetry before.

“There are some people who have literacy issues. I’m very aware of that in different settings, and know that I can’t just put this big poem in front of you, and a pen and a paper, and say, ‘Write a poem,’” Mayson said. “I’m assessing the room. I’m doing open-ended exercises. I’m saying, ‘Hey, if you don’t want to write it down, you could just tell us.’”

At the Open Door Clubhouse, a vocational services organization in Kensington for people with mental health issues, some of the participants were not comfortable writing. Mayson starts with talking.

“What have people been dealing with the last two years?” she asked about a dozen people gathered for the workshop.

Mayson goes around the room as people chime in: “COVID,” “drugs on the corner,” “violence and bloodshed,” “constant change.”

“We just talked about some really heavy things,” she told them. “This project is about: how do we heal?”

One of the participants is Alan Nanes, who has been coming to the clubhouse for 10 years. All that time watching the ups and downs of the neighborhood outside.

He wrote a poem in the workshop that opens with “Kensington is a tough neighborhood.”

“I had family members, I had some uncles and aunts, and cousins who used to live and work here,” he recited. “I have seen many people come and go, but I’m still here.”

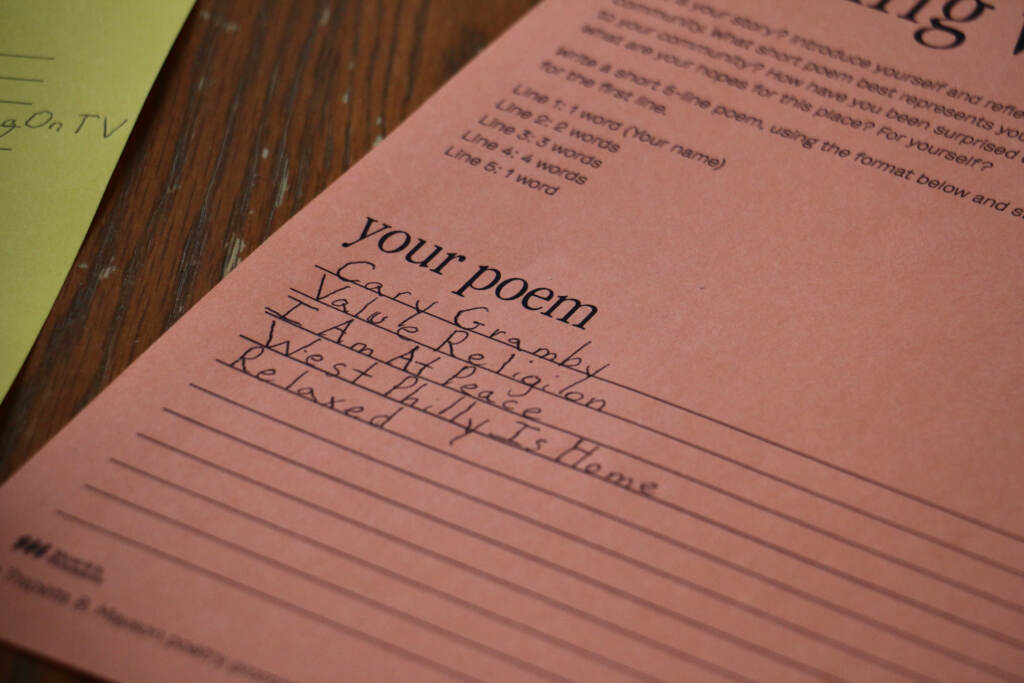

Nanes chose to write about the neighborhood, but Mayson’s poetic prompts are more open-ended than just Kensington. The participants were asked to consider words and phrases that affirmed their own experiences and sensibilities, as a means of celebration. One participant who called himself a “storm chaser” enjoyed writing about the weather.

“All of us – a number of us are walking around with undiagnosed or diagnosed mental illness, and no one’s asking us to write about it,” Mayson said. “We just want them to write about that experience, whatever the individual feels. They could be writing about food, or love, or whatever. That’s your story to tell.”

Mayson works with curator Ryan Strand Greenberg, who was instrumental in getting the neon billboard created. He says there are now no plans to create another public art piece out of the Healing Verse workshops. That’s not the point.

“The downside to a lot of public art making is that once the artwork is up, that tends to be the celebration and the completion. But this tool was such a useful thing for the community,” he said. “There’s such a demand for people wanting to talk about their experiences and share with their community what they’re going through, we thought it necessary to keep it going.”

The Kensington Healing Verse project has a website where anyone can submit a poem on any subject, to be shared with the project’s online community.

One of the more enthusiastic writers at the Open Door Clubhouse was Amaryllis Ruiz. When Mayson asked the group to spend five minutes writing a poem, Ruiz wrote two.

“When you suffer from intellectual disability, sometimes you’re in your head too much. It’s, like, the greatest enemy,” she said. “So in order to have change, you have to be positive and be optimistic, you know, not be a negative Nancy.”

Ruiz lives in North Philadelphia and works at a local Wawa convenience store. She scheduled time off work specifically to be at the Clubhouse to write poems with Mayson.

She writes that people in her neighborhood “feel fiercely.”

We would love for things to be better for the future.

We want to share positivity, progress.

We are soldiers in this world.

After the session, Ruiz had a chance to talk one-on-one with Mayson to ask about her poetry, and how Ruiz might develop her own.

“When you get home from work – whether it’s stressful or nice – write some poetry,” Mayson advised. “After you’ve filled your journal, then go back and start editing. Did I say everything I wanted to say? Did I say too much? We’re not at that point yet. Just keep writing first.”

Ruiz was taking notes the whole time. Mayson said she wanted to see three new poems from Ruiz at the next workshop session, in a week. Ruiz’s notebook was quickly filling with words.

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.