Philly pauses review of school facilities — again — to align with superintendent’s plan

The facilities planning process, which has had multiple starts and stops, is meant to determine the district’s current and future building needs.

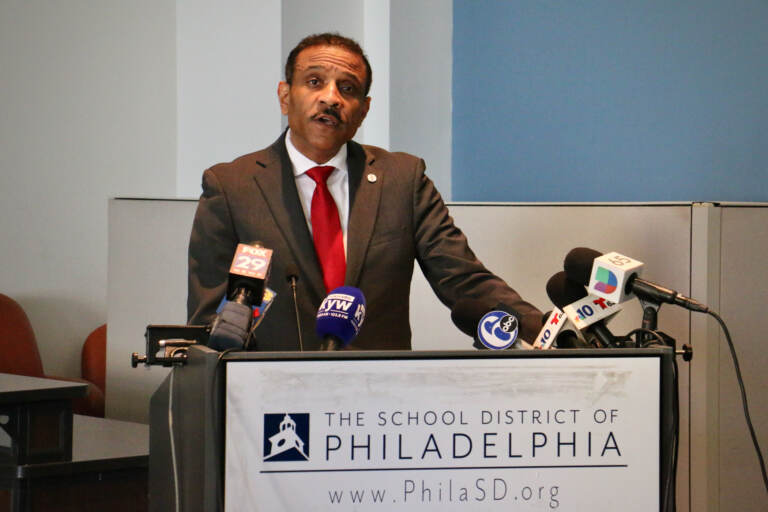

File photo: School District of Philadelphia Superintendent Tony B. Watlington Sr. speaks at a press conference on August 12, 2022. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Philadelphia’s school district will stop work on its facilities plan until after it has a new 5-year strategic plan, Superintendent Tony Watlington said Thursday.

Watlington, who came to Philly from North Carolina in June, began work on his roadmap earlier this month, which he promises will be “aggressive” and lead to dramatic academic improvements for district students.

The strategic planning process has six distinct phases, including multiple opportunities for community feedback, and is expected to wrap up in June. Once there’s a plan, it will be subject to board approval.

Multiple board members at Thursday’s meeting said they supported Watlington’s decision and no one spoke against it.

“I do think there is some history here with the public where this feels like we’ve heard this before,” said board member Mallory Fix Lopez. “How can we assure them that this is different?”

The facilities planning process is meant to determine the district’s current and future building needs. It has had multiple starts and stops, and was last paused in March 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic reached Pennsylvania. Efforts resumed eight months ago with the promise of a report this spring.

Watlington said it doesn’t make sense for the district to come up with a facilities plan until after it has a clear plan for academics since the two go hand-in-hand.

For example, if the district decides all high schools must offer certain AP classes, they need to make sure they have enough and the right type of classrooms, including lab space.

Watlington said facilities planning also needs to align with career and technical education programming.

There’s also the question of how to group grades. Do middle schools benefit students or are K-8 schools best? Watlington said these are just some of the many questions he is trying to answer.

“I don’t have any intention to come back at the end of the school year and say, ‘Let’s delay again,’” Watlington said.

Philadelphia’s school buildings are more than 70 years old on average and more than half lack adequate air conditioning, which led to widespread closures at the start of the school year. The district continues to deal with health hazards in buildings, including asbestos and lead.

The district closed six schools in 2012 and another 24 in 2013 after it started working on its last facilities plan in 2010. Protests followed and the district has promised extensive community engagement since then.

The district’s strategic plan is meant to carry it to 2028 and is expected to have clear yearly goals. In the meantime, the district is also working on plans to “accelerate progress” for students who are currently behind, Watlington said.

While student achievement for some grades increased by several percentage points under his predecessor William Hite, in general, proficiency rates have remained flat. Citywide, just 36% of district students meet state standards in reading and 22% in math. Based on national assessments even more students are behind.

“We are crystal clear and very cognizant of the fact that many of our children and families have immediate needs that need to be addressed,” Watlington said.

Peng Chao, the district’s chief of charter schools, also spoke at Thursday’s meeting and briefed board members on upcoming charter renewals and applications to create new or operate existing schools.

Notably, Chao said the operator applying to run Daroff Charter School, which abruptly closed this fall, and Bluford Charter School, which is set to close at the end of the school year, appears to be its current board just under a different name.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.