Art that stares back: Life-size figures reflect cultural identities at the Clay Studio

The Clay Studio in Philadelphia asked 12 artists to make work that reflects how they feel about their position in the world right now.

Listen 1:21

Roxanne Swentzell's "Put Down the Man Baby"(right) stares past Christina Cordova's "Eva XV," at the Clay Studio's exhibit of human scale sculptures, "Figuring Space." (Emma Lee/WHYY)

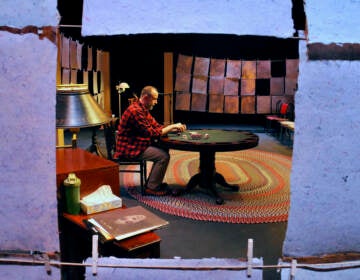

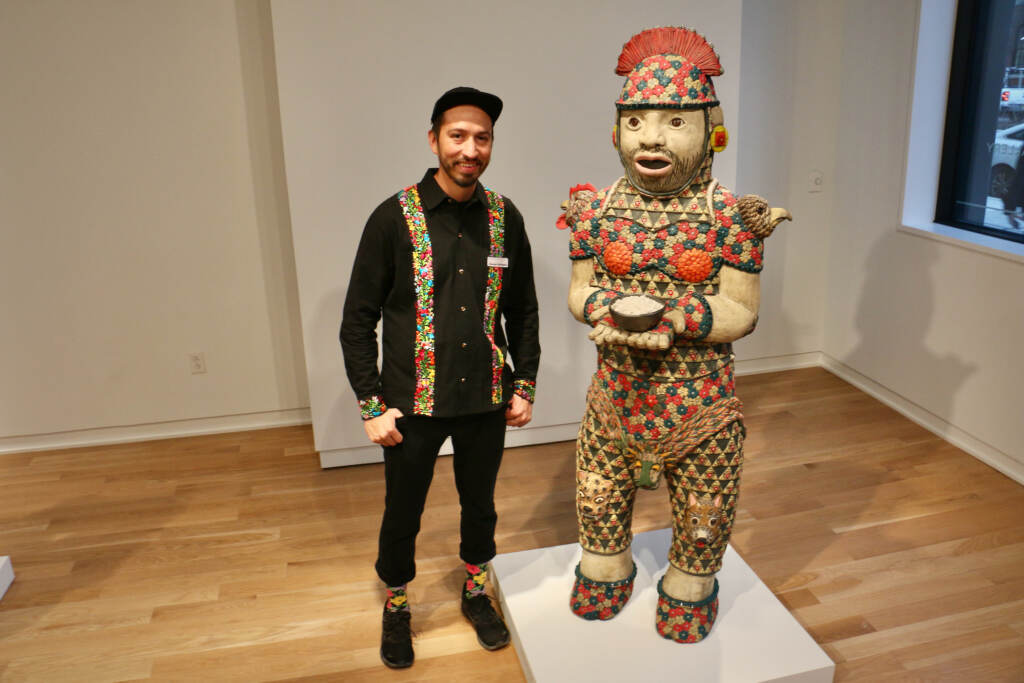

George Rodriguez put his own face on an imagined Mexican antiquity.

His clay sculpture, “Memoria Ancestral,” stands a little more than six feet tall — or roughly the same height as Rodriguez — inspired by a small shamanistic sculpture discovered in the Mesoamerican pyramids of Teotihuacan outside Mexico City.

Rodriguez, 40, grew up in El Paso, Texas. His mother’s family came from the Mexican state of Chihuahua. Rodriguez now lives in Philadelphia and works at Temple University’s Tyler School of Art.

He dressed the figure in a colorful ceremonial outfit festooned with mythological animals, including a blue deer, a Quetzalcóatl winged serpent, a rooster, and a dog. Under the plumage of the headpiece is the bearded face of Rodriguez himself.

“It’s a way to journal a little bit,” he said. “Every now and then I’ll take a step back and figure out where I am in place, in time, and make a portrait.”

Rodriguez’s fanciful doppelganger is one of a dozen life-size figures, by as many artists, greeting visitors at the Clay Studio gallery in Kensington. The artists in “Figuring Space” come from a wide range of backgrounds, and their sculpted figures communicate something about their cultural identities.

Curators Jennifer Zwilling and Dr. Kelli Morgan had worked with the artists for over a year, asking them to create a life-sized figure in clay that reflects their position in society. With a few exceptions, all the work was created in the last 12 months.

“What are the issues that you want to raise? Race, gender, age, disability,” Zwilling said. “How can you make them visible, and then put them in conversation with the viewers where the viewer will see these figures eye-to-eye?”

Some of the pieces are just below eye level. Roberto Lugo, whose work often reflects his upbringing in Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood, created a group of ceramic teddy bears decorated in patterns resembling African batik cloth.

Called “Street Shrine 2,” the group depicts an impromptu memorial shrine commonly seen on sidewalks where someone has been killed.

“I knew exactly right away what he was talking about,” Morgan recalled when Lugo proposed the sculpture. “As a Black woman from Detroit, Michigan, growing up in the ‘80s and ‘90s, those street shrines were everywhere, unfortunately, around my neighborhood. But we knew that was how we remained close to the people we had lost to gun violence.”

Cristina Córdova‘s “Eva XV” is a life-size sculpture of her daughter Eva, in a confident stance. True to the title, Eva turned 15 in 2022.

Córdova, a Puerto Rican artist based in North Carolina, sourced the earthen pigments from specific sites in Puerto Rico: some came from the eastern coast of the island, others from the inland mountains. On Eva’s back are the words, written in gold, “de monte y mar” (“from mountain and sea”), lyrics from “Verde Luz,” an anthem of Puerto Rican nationalism by Antonio Cabán Vale.

“The image of Eva is the embodiment of change and possibility,” Córdova wrote in a statement.

“Representation matters: a phrase often used, but appropriate,” Zwilling said. “We wanted people to feel welcome; that when they came in they could both find someone that looked like them and also feel connected to the figures that don’t look like them because of other reasons — the emotion that’s being shown and feeling connected and having a meaningful experience.”

One of the more prominent ceramic artists on view is Tip Toland, whose work has been described as “hyper-real,” a phrase Toland doesn’t like.

“I call it accuracy, rather than hyper-realism,” Toland said. “I just wanted to be accurate.”

Toland is originally from Swarthmore, Pa., now living and working on a peninsula in the Puget Sound near Tacoma, Washington. Her piece, “Love Song for Ukraine,” captures a moment of youthful bliss amid the current war.

An 11-year-old girl is languidly lying on a green cot commonly used for displaced people. Her blue hair pokes out from a yellow kerchief, and she is playing the harmonica, an instrument Toland, herself, used to play.

“My grandmother gave me a harmonica when I was a kid — I was about 11, the same age as she is,” Toland said. “I could entertain myself for a long time. I loved that the in-breath was one note and the out-breath was another one. I just loved it.”

Toland’s pieces typically tell some kind of narrative story, and while Toland has no direct, personal connection to the war in Ukraine, she wanted to empathize what it would feel like to be a girl whiling away the time in a refugee camp.

“She’s just by herself in this camp, entertaining herself and playing this love song,” she said. “It’s a sweet piece. It’s melancholy, for sure, but it’s also just her private world.”

Like Toland, Jonathan Christensen Caballero‘s piece “Seeds of Tomorrow/Semillas del Mañana,” comes from an act of empathy. The artist from Lawrence, Kansas, often makes work based on the lives of immigrant laborers.

“Seeds of Tomorrow” is inspired by people from Latin American countries who came to Kansas in the 19th and early 20th centuries to work for the Sante Fe Railroad company. The two figures, suggesting a mother and daughter, have terra cotta faces and hands that Caballero life-cast from models, which he then stylized with headpieces reminiscent of ceremonial headgear used by indigenous people around Durango. The figures appear to be harvesting a garden.

Their bodies are made from second-hand clothes that have been torn into strips and wrapped into a solid mass. The woman’s torso, for example, was made from denim reclaimed from about 50 pairs of used jeans.

“The materials that I’m constantly choosing are in reflection of what resources people have access to when they work within these labor communities,” Caballero said.

Caballero made “Seeds of Tomorrow” while in residence at the Lawrence Arts Center, in Lawrence, Kansas, basing the work on the oral history archive in the Watkins Museum of History. The artist himself is not from that area — he grew up in Ohio — but feels a kinship with the community of immigrant laborers and their descendants: his mother immigrated from Panama and worked mostly in a school cafeteria.

“Thinking about all of … the infrastructure, the food, everything around us and what does it take to get these things to us, maintain our bodies, maintain our society,” he said. “About politics, really, and a very public hatred towards the Latin American community. It’s in response to that, trying to, like, ‘No, we are contributing to the United States, not necessarily just taking. We are part of the fabric of this country.’”

“Figuring Space” will be on view at the Clay Studio until April 16.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.