Food fight: The history of the school lunch at Philly’s Science History Institute

Philadelphia pioneered the school lunch 130 years ago.

Listen 1:46

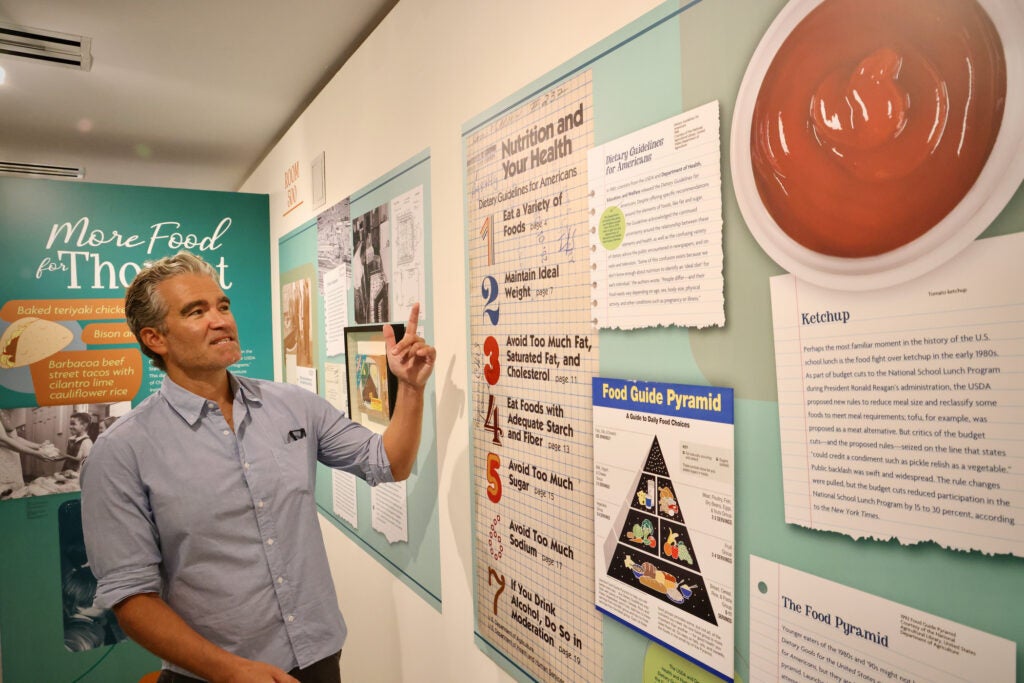

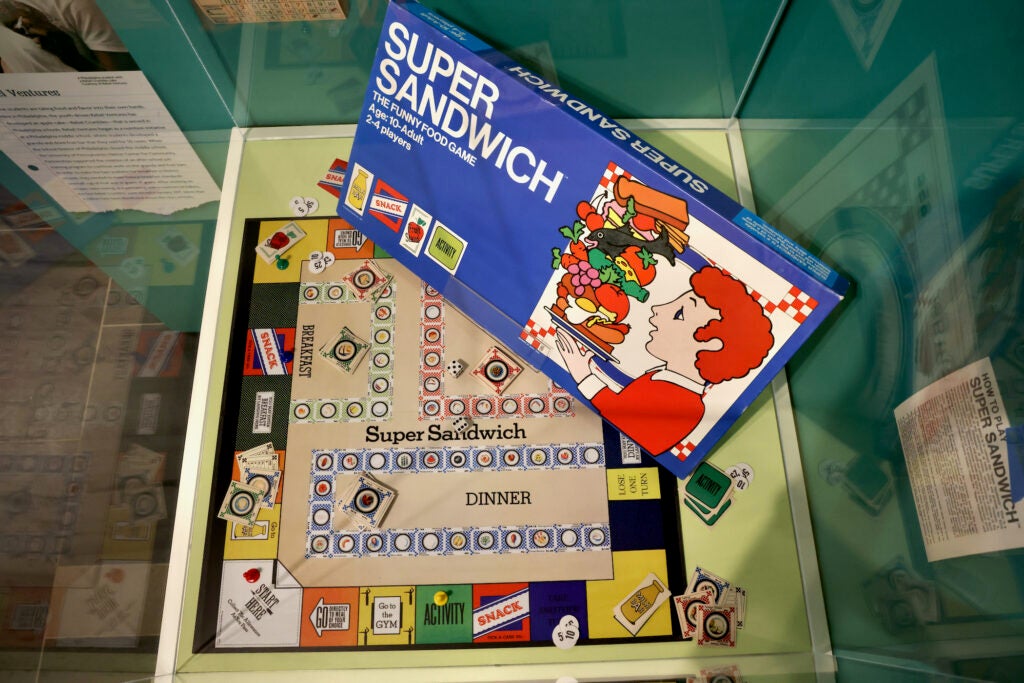

An exhibit at Philadelphia's Science History Institute looks at food science through the lens of the school lunch program. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Few things sit so centrally at the intersection of science, politics, health, and culture as the school lunch.

By the early 20th century, most states in the U.S. had some form of compulsory education: kids had to go to school. If the government could force kids to go to school, should it also feed them?

If so, what?

“The history of school lunches is a history of conflict,” said Jesse Smith, director of curatorial affairs at the Science History Institute in Old City. “People have always been arguing over school lunches, up through the present moment.”

Smith curated “Lunchtime: the History of Science on the Food Tray.” Just days before it opened, school lunches were once again in the news. A minor political skirmish popped up in Washington as congresspeople clashed over a bill that would offer free meals universally to all students, regardless of income eligibility.

The universal free meals bill is tied to a USDA rule that participating schools must have anti-discrimination policies in place, in accordance with President’ Biden’s executive order on racial and LGBTQ equity. Some Republican members of Congress oppose that rule.

“The Biden Administration’s poisonous transgender agenda is putting children’s school lunch funding in the crosshairs,” said Roger Marshall, a Republican Senator from Kansas, as reported by The Hill newspaper.

In Philadelphia, universal free lunches have been in place in the school district for the last 10 years per the USDA’s Community Eligibility Program, which reimburses the cost of meals to all students, regardless of income, at schools in high-poverty areas.

Across the state, all students have access to universal breakfasts, while free lunch in most of Pennsylvania is tied to income eligibility.

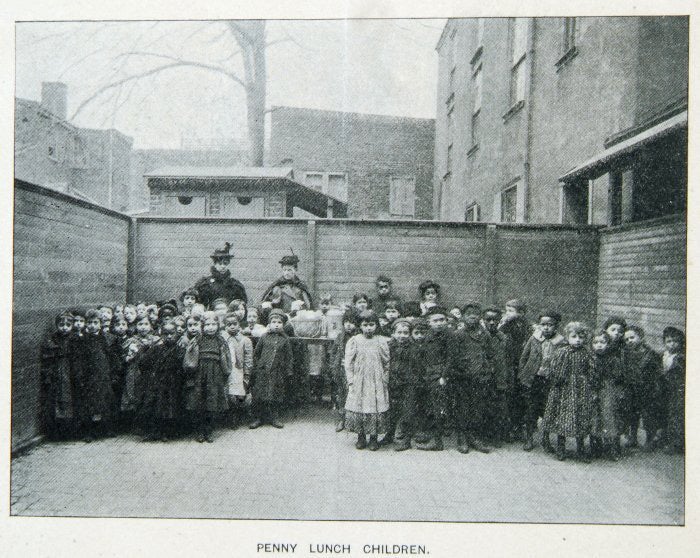

Historically, Philadelphia has been at the forefront of feeding kids in school. In 1894, along with Boston, the two cities were the first to offer meals to students. In Philadelphia, the program was in just a handful of schools and was operated by a community service organization, the Starr Centre Association.

Students paid for a “penny lunch” with a prepaid token worth one cent, an example of which is on display in Lunchtime. In 1910, the Philadelphia School District adopted the Starr lunch program and expanded it to all the city’s public schools.

Lunchtime, the exhibition, is designed with a mid-century modern pop aesthetic — all pastel colors and bubble graphics — circa 1946 when President Harry Truman signed the National School Lunch Act, providing free or low-cost lunches to eligible students.

However, 1946 is the midpoint of this story. It began in the late 19th century when populations were shifting from agricultural areas to urban ones for factory work. Business tycoons seeking ways to keep their workforces productive looked toward new research in nutrition science to determine what, exactly, is needed to sustain a worker.

“Fuel, in the broadest sense, is critical for what we know as the Industrial Revolution,” Smith said. “Things like coal, but also the food that is feeding the individuals who are laboring in these factories.”

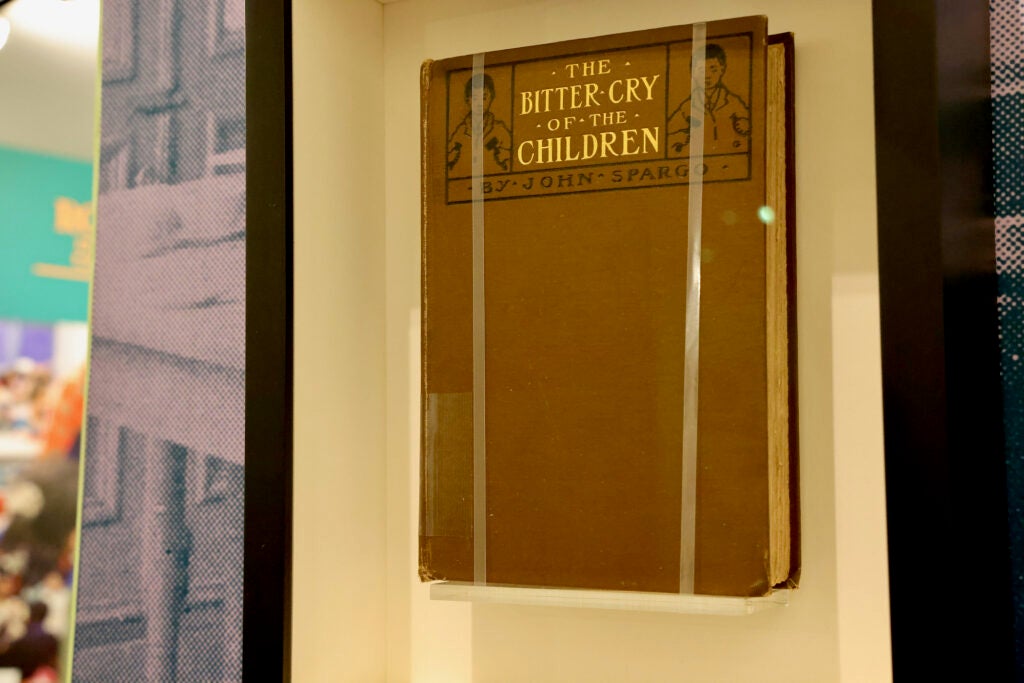

But if kids are left to make their own dietary decisions, those choices are rarely wise. In 1907, journalist John Spago published a scathing book about children’s lives in factories and schools, “The Bitter Cry of the Children.” He saw children buying themselves a lunch of ice cream and cigarettes.

At the turn of the century, most schools did not offer any kind of lunch. Children had to either bring their own from home or buy food from nearby stores and street carts. Lunchtime shows that in 1910, the Columbia Teacher’s College recorded children at school eating frankfurters and rolls, bananas and licorice, Swiss cheese bread, and frosted cakes.

“We wanted to highlight some of the meals that students would have been eating at the time,” Smith said. “I think that today, we have a sense of what iconic school lunches might be — things like fish sticks and Salisbury steak — but at other times, it might have been liver loaf and cheese rice souffle.”

The first dietary recommendations from the USDA came in 1916, suggesting children aged 3-6 eat a lamb chop, chopped spinach, rice with milk and sugar, bread and butter, and baked potato.

During this period, states passed compulsory education laws; Mississippi was the final to do so in 1918. However, few schools were offering lunch, and those that did were not accountable to USDA or other guidelines.

The logistics of the modern school lunch were formally developed in 1920 by the Philadelphia School District’s lunch czar, Emma Smedley, in her book “The School Lunch: Its Organization and Management In Philadelphia.”

“This was a manual that explained what she was doing in Philadelphia: menu planning, hiring, the organization of storage spaces,” Smith said. “Things we might take for granted today but were all being developed from scratch at the time.”

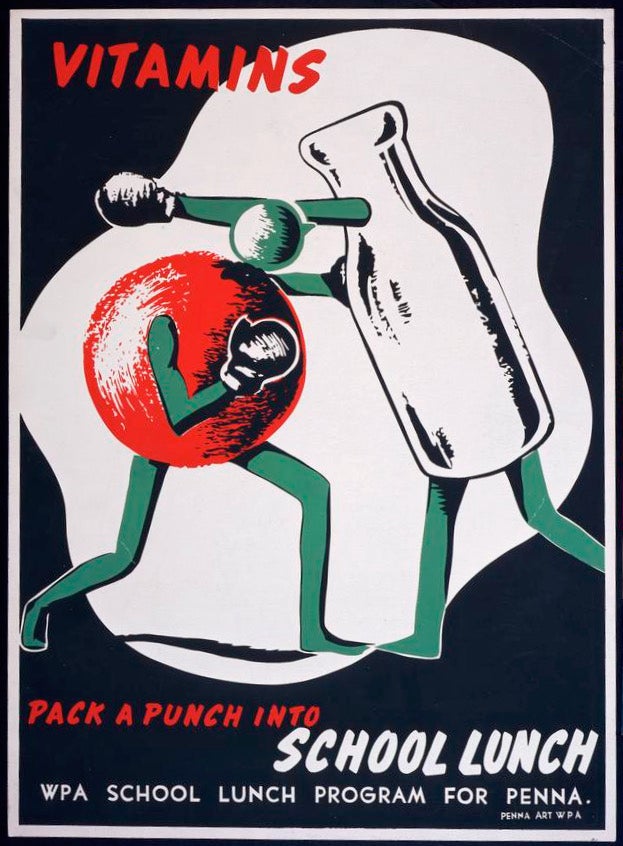

By the 1930s and 40s, global forces began to shape the school lunch. Advances in agricultural science, particularly new synthetic fertilizers, were generating unprecedented amounts of food.

The National Fertilizer Association was so proud of its accomplishments that it produced a truly bizarre piece of pop culture in 1951: a comic book called “The Conquest of Hunger” featuring happy, well-fed children going on adventures with an anthropomorphized bag of chemical fertilizer.

Crops were booming, but fewer people could afford them when the Great Depression hit in 1929. The U.S. government bought surplus agricultural products and donated them to schools to keep farmers afloat. The Works Progress Administration hired thousands of people to prepare and serve lunches in schools across the country. Thus was born the free lunch.

World War II created an urgency for nutrition standards. Six months before the U.S. entered the war, President Franklin Roosevelt called a National Nutrition Conference for Defense: “Fighting men of our armed forces, workers in industry, families of those workers, every man and woman in America, must have nourishing food,” he wrote.

(Courtesy Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia)

The Conquest of Hunger by WHYY News on Scribd

After the war, President Truman made school lunches official by signing the National School Lunch Act of 1946, which provided free or low-cost lunches to eligible students.

“It’s a pretty contentious act,” Smith explained. “It’s supported by a lot of Southern senators and representatives, but they are very worried that this represents federal incursion into the operation of schools. They see it as a threat to segregation.”

The Act gave states the power to administer school lunches, including how to distribute resources and surpluses. Some local administrators were able to perpetuate racial inequities by deciding which schools would benefit from federal assistance. Lunchtime says that, by the end of the 1950s, less than a third of American schoolchildren were being fed at school.

The food fight continued as the USDA tinkered with nutritional guidelines. What started as five food groups in 1916 fluctuated greatly, anywhere from four to twelve food groups. In 1992, a pyramid structure was created to determine how much of each food group could be eaten. Today, the USDA uses MyPlate, a dinner plate graphic with five food groups.

Lobbyists for various food and agricultural industries pushed back at every turn, as changes to federal nutrition recommendations might lessen the consumption of certain foods.

Lunchtime features one of the most memorable moments in modern school lunch history: in 1981, the Reagan administration cut the federal school lunch budget by about $1.5 billion. Looking for ways to stretch funds, the USDA allowed schools to serve ketchup to satisfy its vegetable requirement.

Although widely mocked at the time — the policy allowing some condiments to be regarded as vegetables was rescinded a month later — the USDA did it again 30 years later by allowing pizza with at least two tablespoons of tomato paste to satisfy the vegetable requirement.

“Whenever we tell someone about this exhibit, they mention ketchup. It seems to be one of the few elements of school lunch history that people know about,” Smith said. “We felt the need to include that in here, but hopefully visitors are encountering significantly more history behind this program.”

“Lunchtime: The History of Science on the School Food Tray” will be on view until January 2026.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.