Incarcerated artists from different prison systems collaborate in ‘The View From Here’

In a rare exhibition, incarcerated artists from SCI Phoenix, Pa., and San Quentin, Calif., form a group show at Philadelphia’s Paradigm Gallery.

Listen 1:13

Eduardo Ramirez takes photographs at ''The View From Here'' at Paradigm Gallery. Ramirez made two paintings for the exhibit while he was incarcerated, including ''Radiohead,'' (left). After he was exonerated in November, he helped curate the show. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Artists incarcerated inside State Correctional Institute Phoenix, in Montgomery County, collaborated with their counterparts inside San Quentin Rehabilitation Center, near San Francisco, California, to stage an art exhibition.

“The View From Here” is on view at Paradigm Gallery in Philadelphia’s Old City.

The bicoastal show features over 40 pieces by 23 artists serving sentences of various lengths. The artists communicated with one another through letters, many of them written longhand and delivered via two organizations operating art programs inside each facility: Mural Arts Philadelphia and the William James Association.

“We’re not allowed to bring paper inside the prison,” said Phoebe Bachman, a facilitator with Mural Arts. “Which is very hard as an art program.”

Bachman described a system by which letters written by men in San Quentin, for example, would be scanned by the facilitators of the William James Association and emailed to Bachman, who would then forward them to officials inside Phoenix and request they print them out in the prison offices.

“There are certain limitations about being someone who is currently incarcerated reaching out to someone else who is currently incarcerated,” Bachman said. “We tried to circumnavigate that by using the art programs to create this through-line for correspondence.”

Due to the difficulty of putting incarcerated people in direct contact with people held in other facilities, “The View From Here” is unique even among prison art exhibitions.

“It opened up interest in the exhibit, because they knew it was an unusual collaboration,” said Carol Newborg, who manages the art program in San Quentin for the William James Association. She has been teaching art in California prisons since 1983.

“We actually have a lot of shows going on, and not everybody does work for every show,” she said. “But a number of guys were interested in working for this context.”

Most of the letters, which are on view in the art exhibition, are introductory, announcing themselves to other artists who are strangers. They describe prison conditions, the resources available to make art and a little insight into what compels them to create.

“Art, for me, is not a hobby. It is to me a form of rehabilitation,” wrote Jeffrey Isom of San Quentin, who has been incarcerated for 19 years.

Isom wrote that he sends his earnings to people in the communities where he once committed crimes “to make a living amends to all those I hurt in the path I took.”

It’s complicated to know which artworks on view are for sale. The Pennsylvania prison system allows Mural Arts to broker art sales by people currently incarcerated in SCI Phoenix. But, in California, the William James Association cannot represent sales.

Newborg said artists in San Quentin sometimes donate works to nonprofit auctions or may connect directly with buyers, but “it’s a grey area” among the colorful art.

The exhibition boasts a single artist who is not incarcerated. Eddie Ramirez, formerly of SCI Phoenix, was exonerated last November. The murder conviction that kept him in prison for nearly three decades was dismissed.

“Twenty-seven and a half,” Ramirez said. “Every day counts.”

Like many artists in both Phoenix and San Quentin, Ramirez’s participation in art projects factored toward his required work detail.

“I didn’t want to work in the kitchen. I didn’t want to work in a plumbing shop. I definitely didn’t want to push a broom down a dusty hallway,” he said. ““[Art] is the thing I’m most passionate about.”

Ramirez said he wanted to correspond with the guys in San Quentin to learn more about the art program there. William James Association has run art programs in select California prisons since 1977. Since 2017, it has been part of the California Arts in Corrections partnership that runs programs in all the state prison facilities.

San Quentin also facilitates a longstanding prisoner journalism project, The San Quentin News, written by incarcerated people and distributed to all the correctional facilities in the California system.

Last year, the California legislature committed $380 million to expand San Quentin into what Governor Gavin Newsom envisions as a model for prisoner rehabilitation.

“I imagined that, if they could do that, their art program had to be something spectacular,” Ramirez said.

The programs at San Quentin and Phoenix are not the same. San Quentin has a larger and better-resourced program with classes that nearly anyone in the facility can access. Those who work in the program as teachers or assistants earn work credit.

The program Mural Arts runs inside Phoenix is smaller. Everyone who participates gets work credit, but the program is limited to select participants.

Both inside Phoenix and now outside, Ramirez has been a cheerleader for prison art programs. In his letter to San Quentin addressed to the general artist cohort, he expressed his belief in the power of art to change people and institutions.

“I take every opportunity to promote the work being done here,” he wrote in March 2023. “Not only would the expansion of art programs further facilitate the goals of corrections and rehabilitation, but I believe that by supporting the arts, we can spark dynamic conversation about justice and community.”

The artists interpreted the theme of “The View From Here” in many ways. Some took it literally, painting what they saw: the pill line where incarcerated people would queue for medications, the workout room, a delicate watercolor of walls and a guard tower.

Other artists took a more political stance and painted images related to criminal justice reform: a realistic portrait of a man sitting casually in an electric chair with the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania seal behind it, making a statement about so-called “Death by Incarceration,” or prison sentences designed to effectively be death sentences.

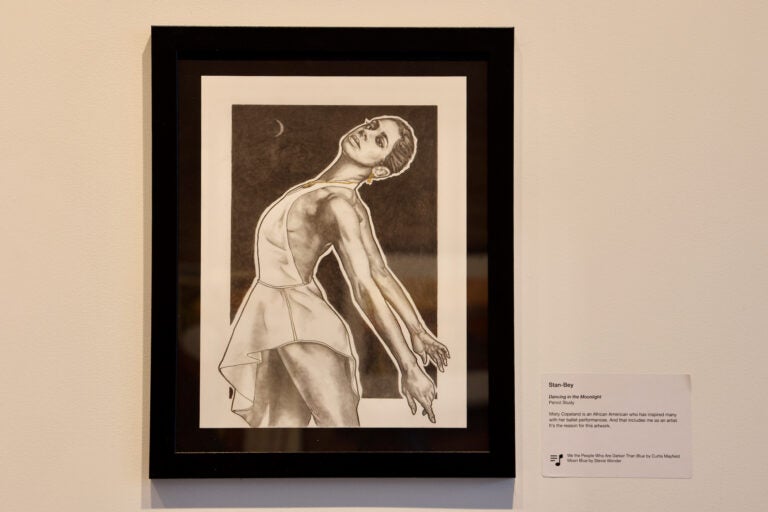

Others internalized the title of the show, imagining images that have nothing to do with incarceration: a bucolic scene of a hunting dog chasing quail; a train rushing through a purple and golden sky of the Rocky Mountains near Denver; a graphite portrait of the ballerina Misty Copeland.

One artist painted a picture of Machu Pichu, an icon of his native Peru but one he has never visited.

“I was just in San Quentin in January,” Bachman said. “I was talking to them about why they submitted the artwork, and they’re, like, ’I don’t want to focus on prison. I spend enough time thinking about prison. What I want to focus on is where my mind wanders from here. I want to think about the dreams that I have.’”

“The View From Here” will be on display on the third floor of the Paradigm Gallery until March 24. Afterwards, it will travel to the Bay Area, where it will be exhibited at the Mill Valley Library and then at the Richmond Art Center.

When the show travels to California, Ramirez hopes to go with it, and meet the guys in San Quentin he has only known through letters.

“I hope to go out there and visit them personally,” he said. “And thank them for giving me this glimpse into their world that I had to imagine.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.