In service and in crisis: How masjids and funeral homes are navigating Philly’s gun violence emergency

One imam is running out of space to bury Muslims. Others worry about their mental health as funeral directors confront tragically unprecedented demand.

Listen 4:18

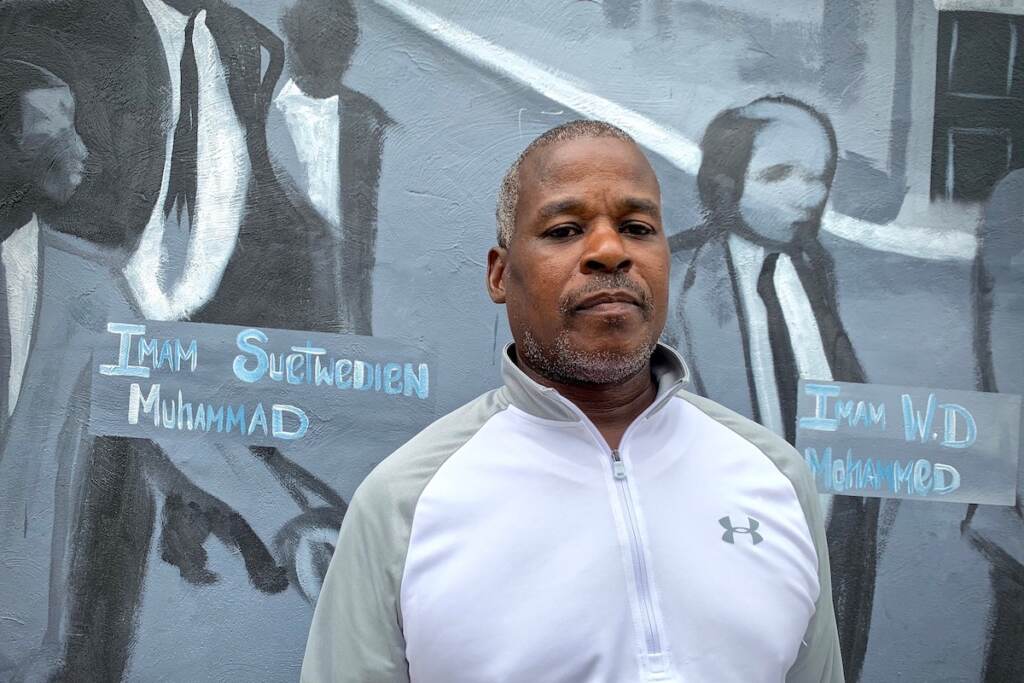

Michael Forrest is the director and owner of Forrest-Walker Funeral home in West Philadelphia. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Ask Imam Suetwedien Muhammad how he knows Philadelphia is experiencing a historic surge in gun violence and he’ll give you three chilling answers.

By the numbers, he’s officiating far more funerals.

In past years, he’s averaged three funeral services a month. For the last two years, he’s been presiding over five a week. All of them for gunshot victims.

“It doesn’t look like there’s no end in sight,” said Muhammad.

The monthly electric bills at Masjid Muhammad of Philadelphia, the sizable house of worship he leads in Germantown, are another indication. They’ve doubled because more families are using the three-floor facility for their repasts, in part because it’s considered safer than inviting people back to the neighborhood where the shooting occurred.

But it’s perhaps the cleric’s final piece of evidence that’s most striking.

Concerned about the area’s dwindling supply of Muslim burial plots, Muhammad started reaching out to local cemeteries to see how much land they have available for purchase because he doesn’t want to be caught scrambling for space.

He’s currently in negotiations with four cemeteries.

“We’re definitely going to need it,” said Muhammad of the additional plots.

As of Wednesday, at least 431 people had been murdered so far this year in Philadelphia, a 14% increase compared to the same time in 2020, the deadliest year in three decades. Most of them were gunshot victims.

For funeral directors across the city, the unrelenting gun violence has meant more business, but also more emotional and physical stress as they guide family after family through a process rooted in the pain and grief that comes with losing a loved one to homicide.

The responsibility weighs heavily on Muhammad, a longtime anti-violence advocate. Particularly because so many of the people he buries each week are teenagers and young adults — lives cut short before they truly started.

He said that makes it that much harder to process it all.

“I try to give it to God, and talk it out with God, because it is so disheartening and it’s also so lonely,” Muhammad said.

West Philadelphia funeral director Michael Forrest can relate. It’s why he does his best to leave his work at the office.

At the end of each day, he goes home, looks into his children’s faces and resets.

“I would have PTSD. I couldn’t do it,” said Forrest during a recent interview inside his tidy business, Forrest Walker Funeral Home, in West Philadelphia.

The job still takes a toll.

Unlike a lot of his counterparts, Forrest has his hands on every step of the business. He said all of them are more taxing when he’s working with a family that’s lost a loved one to violence.

“I don’t necessarily get blamed for it, but sometimes I’m the punching bag because I’m the one that they can lash out upon because I’m sitting there. I’m an easy target,” he said.

Forrest does all of the embalming. The process puts him face-to-face with every gunshot victim who comes through the doors of his Cobbs Creek funeral home.

And it’s not a short process. Embalming a person who was fatally shot can take up to five hours — more than twice as long as it typically takes to preserve someone who died of natural causes.

“You can have multiple gunshot wounds and you have to sew those holes. You have the examination that the medical examiner does, whatever cuts they may have to get. And you have to put these people back together and make them presentable — as if it never happened,” Forrest said.

Arranging more funerals for gunshot victims has also made his business more dangerous.

Even before the current citywide crisis, Forrest said it wasn’t unusual for the perpetrator of a shooting or a member of a rival street group to poke their head into a funeral service. And he said there’s always the possibility of someone showing up to a church or cemetery to fire off a few shots, typically from a moving car.

“Some want revenge, some want to make a point, some want to scare the family,” Forrest said.

When it happened last year, Forrest wanted to run.

“I don’t want to get caught up in somebody else’s beef, for lack of a better term, and just become a statistic because I was in the wrong place at the wrong time,” he said.

He worries about his staff getting hurt too.

For Escamillio Jones, one of the hardest things about being a funeral director right now is that he’s starting to see the same faces at services because people are losing multiple family members and friends to gun violence.

The grim reunions have sparked some uncomfortable exchanges inside Escamillio DeEstiss Jones Funeral Home in Juniata Park.

“One guy came walking in and he just did one of those numbers like ‘here we go again,’” said Jones. “I just shook his hand and he said, ‘I really don’t want to see you anymore,’”

“In my mind, I’m thinking, ‘the way things are going, we are going to see each other again. It’s just the nature of Philadelphia right now.’”

Jones said it’s also been harder than ever to find time to decompress because he never knows when tragedy is going to strike next. A phone call from a grieving family member could come any day at any time, said Jones.

Last year, during a quick getaway to Chicago with his wife, the couple’s meal was interrupted by a call from a grieving family who needed to make arrangements. Similar scenarios have played on vacations and during family functions.

And yet, Jones said there’s nothing else he’d rather do.

“I’m just willing to serve at any time. I feel like God created me for this position,” he said.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.