Historical Society of Pennsylvania shows how Philadelphia took care of its own

An exhibition of the long history of charity and philanthropy in Philadelphia shows its cracks and possibilities.

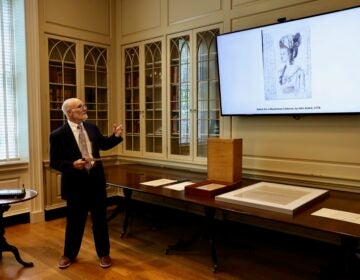

Katy Bodenhorn Barnes, genealogy director at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, curated ''Brotherly Love and Sisterly Affection,'' an exhibit that looks back at the charitable and mutual aid institutions that provided social safety nets in the 19th and early 20th centuries. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

As the post-Thanksgiving Giving Tuesday event approaches — launching the end-of-the-year season of donation requests by nonprofits and charities — the Historical Society of Pennsylvania is taking a look back at Philadelphia’s history of social aid programs.

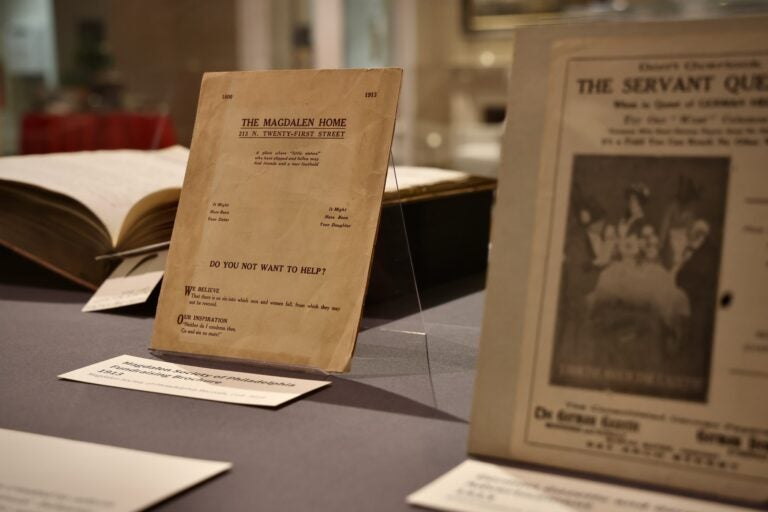

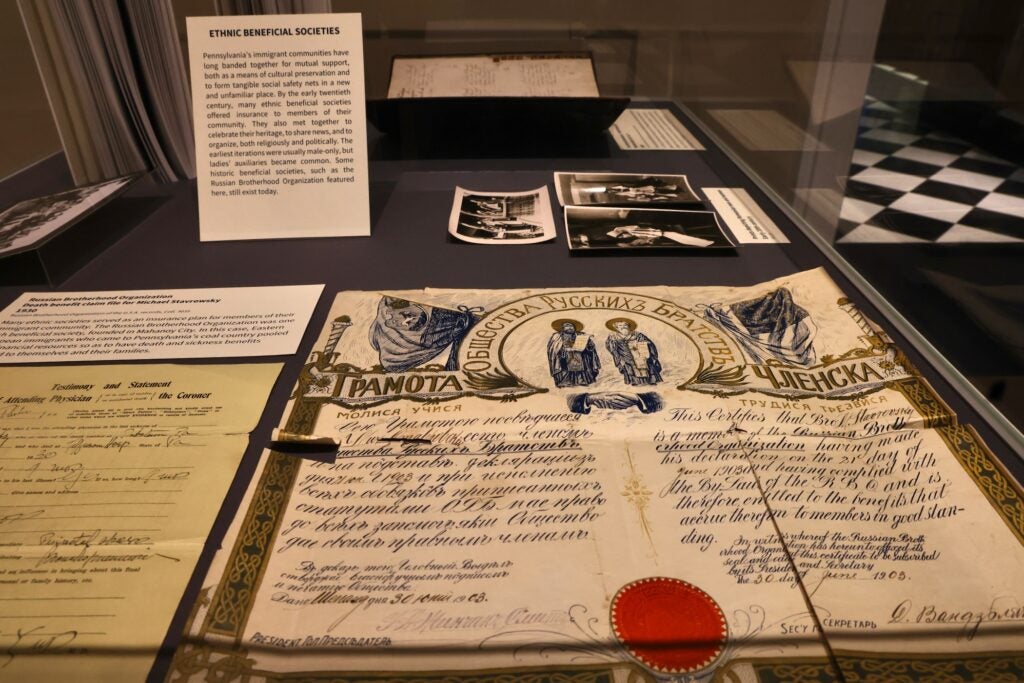

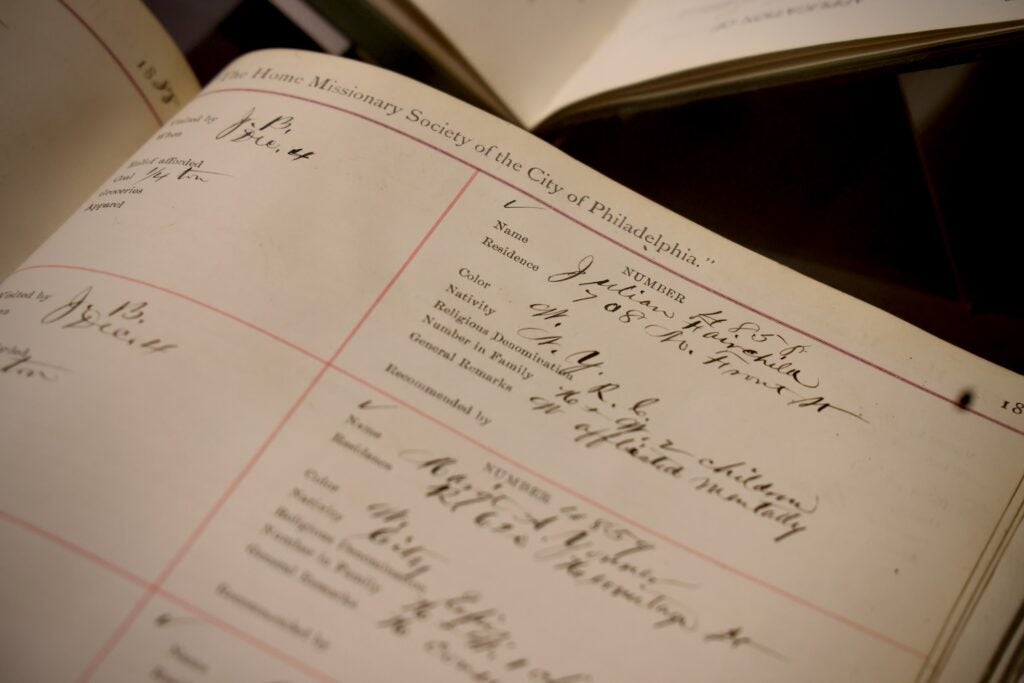

Four display cases in the exhibition “Brotherly Love and Sisterly Affections: Tracing Families in Social Service Records” feature photos and manuscripts from the HSP archives. These items highlight individuals who benefitted from organizations such as the Franklin Reformatory Home for Inebriates of Philadelphia, the Indigent Widows and Single Women’s Society of Philadelphia, or the Philadelphia Superintending Committee of Soldier’s Orphans.

Despite their sometimes-unwieldy names, these well-intentioned charities — often spearheaded by the city’s wealthiest class — were formed to assist Philadelphians who fell on hard times when there was little in the way of public support.

“This is in the days before welfare, food stamps, and a lot of government services that we have now,” said curator Katy Bodenhorn Barnes, HSP’s director of genealogical services. “As new services came along that could do that more systematically, there wasn’t as much need, and they could put the resources elsewhere.”

“Brotherly Love and Sisterly Affections” is the final exhibition of HSP’s year-long rotation of shows marking its 200th anniversary.

Barnes’ interest in the benevolent societies of the 19th century stems from her work as a genealogist. Many individuals logged by these organizations appear nowhere else in the historical record.

”For a lot of people, especially people of color or the very, very poor, they’re not going to show up in property records as landowners,” she said. “Women who changed their name when they get married, it’s very easy for them to fall through the cracks. Orphan children — it’s not like now where there is formal adoption paperwork.”

Barnes said the exhibition evokes strong responses from some visitors.

“A lot of people have these ties, you know: ‘I had an adopted grandparent or great-grandparent, and I knew that she had a really traumatic background, and it’s bringing tears to my eyes to come and read these stories of children,’” she said.

One of the earliest organizations on display is the Orphan Society of Philadelphia, which was formed in 1816.

The group’s goal was to divert “fatherless” children away from almshouses, where destitute children were normally sent to live among the general adult population and could sometimes have extremely bleak and harrowing conditions.

As the city’s first privately funded orphanage, the Orphan Society building at 18th and Cherry Street housed children — who had to be white and at least seven years old — to educate and give them job training. In reality, many were bonded out as uneducated indentured servants. One person who endured the program as a child recalled it as “slavery.”

Later, in 1882, the Children’s Aid Society was formed as an alternative to the Orphan Society, placing children into adoptive foster families instead of ushering them into the workforce.

The Orphan Society was formed by a committee of wealthy Philadelphia women, notably Sarah Ralston and Rebecca Gratz, who each took the role of social reformer very seriously.

Gratz, the daughter of a wealthy Jewish merchant, also formed the Female Association for the Relief of Women and Children in Reduced Circumstances, the Female Hebrew Benevolent Society, and the Hebrew Sunday School. Gratz College in Elkins Park is named after her.

“She never married,” Barnes said. “She did things like put her money and her time toward doing that kind of public service.”

Ralston, the daughter of onetime Philadelphia mayor Matthew Clarkson, also formed the Indigent Widows and Single Women’s Society, which ultimately became the Sarah Ralston Foundation supporting elder care in Philadelphia. The historic mansion she built to house indigent widows still stands on the campus of the University of Pennsylvania, which is now its chief occupant.

Women like Ralston and Gratz were part of the 19th-century Reform Movement that sought to undo some of the inhumane conditions brought about by the rapid industrialization of cities. Huge numbers of people from rural America and foreign countries came into urban cities for factory work, and many fell into poverty, alcoholism, and prostitution.

“These are not new problems, but on a much larger scale than they ever were,” Barnes said. “It was just kind of in the zeitgeist in the mid- and later-1800s to say, ‘We’ve got to address all these problems.”

The reform organizations could be highly selective and impose a heavy dose of 19th-century moralism. The Indigent Widows and Single Women’s Society, for example, only selected white women from upper-class backgrounds whose fortunes had turned, rejecting women who were in poor health, “fiery-tempered,” or in one case, simply “ordinary.”

The Magdalen Society, under the leadership of the first bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania, William White, was formed as an asylum for “fallen” women, a definition that went beyond prostitution to any woman who fell outside the organization’s moral code, so long as they were not Black or pregnant.

“A lot of these women just fell into what might have been considered a bad crowd,” Barnes said. “They might have had sex outside of wedlock. Even if that didn’t result in pregnancy, if it was just socially known, that could be a problem.”

One such woman was Emma Pickram, an unmarried woman in her 30s who had been living with a man for 16 years. The Magdalene Society married them in 1879 in the parlor of its asylum on Race Street near what is now the Franklin Institute.

“They saw a stable, functioning society as exclusively held up by married heterosexual couples living a very specific way,” Barnes said.

Most of the organizations on display no longer exist. Some evolved through a series of mergers and changes into the present day: the Orphan’s Society ultimately morphed into Turning Points for Children; the Magdalene Society became the education advocacy organization Heights Philadelphia.

As the next Trump presidential administration prepares to enter the White House, many in the philanthropy field are reportedly anxious about perceived threats to governmental social services. The Project 2025 plan by the Heritage Foundation, to which several of Trump’s team are closely aligned, suggests cutbacks or eliminations to federal health, environmental, poverty, and education programs.

After Trump’s 2024 victory, nonprofits such as the ACLU saw dramatic spikes in donations. With the January inauguration still several weeks away, they are hoping philanthropy will be similarly enthusiastic again.

“Brotherly Love and Sisterly Affections” was planned well in advance of the most recent election. Barnes says the exhibit spotlights a time when private citizens filled gaps left open by the government.

“I get feedback that it’s important,” she said. “It’s important to remember how things used to be, because as important and helpful as these philanthropic organizations were, they couldn’t help everybody. There were still a lot of people that fell through the cracks, sometimes intentionally by the people they chose to serve or not serve.”

“Brotherly Love and Sisterly Affections” will be on view until November 27 at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1300 Locust Street in Philadelphia.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.