School funding in Pa. has to change. Does N.J. have the answers?

In a landmark court decision, Pa.'s school funding system was ruled unconstitutional. Now, lawmakers have to address its underlying inequities.

Listen 35:39

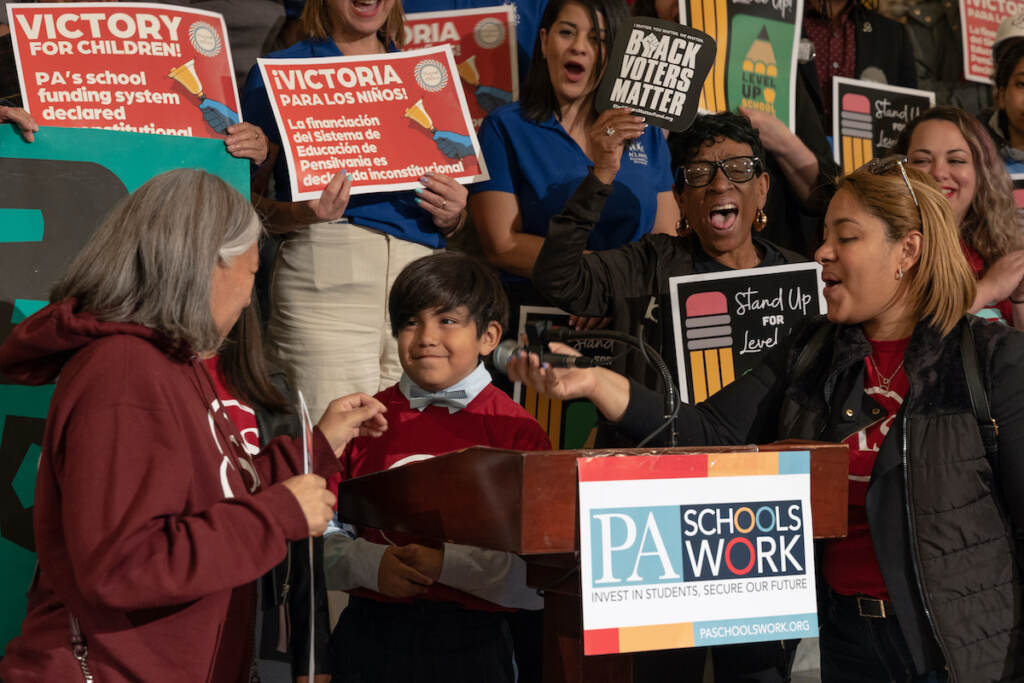

School funding advocates rally at Pennsylvania’s Capitol in April in response to the state’s historic school funding ruling. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

This episode is the third in this season of “Schooled,” a podcast production from WHYY that gives the insider’s story of public schools, through the eyes of students, parents, and educators.

Read and listen to the first episode and the second episode.

Find “Schooled” on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Silvia Abbato knows what it’s like to have a bad reputation.

The long-time educator remembers how other New Jersey school leaders used to respond decades ago when they heard she was from Union City. “They’d say, ‘Oh, the Dirty 30.’”

Back then, the schools in Silvia’s hometown were among the lowest-performing in the state. She says it wasn’t the fault of students or staff — the problem was underfunding.

“The money wasn’t there and there wasn’t that commitment from the state.”

The “Dirty 30” referred to the roughly 30 poor, urban school districts in New Jersey that were part of a lawsuit filed against the state in the 1980s. It closely mirrors Pennsylvania’s school funding case today.

Silvia is the superintendent of Union City’s schools, and says a lot has changed since then.

“Now it’s like, ‘Oh my God, you’re doing such wonderful things.’”

So what happened?

The poor, urban districts won their case, and New Jersey eventually gave them a lot more money.

Educators and politicians in Union City capitalized on this opportunity, spent the money wisely, and ultimately pulled off a dramatic turnaround — a saga chronicled in detail by David Kirp in his book “Improbable Scholars.”

“It is very heartwarming and wonderful when you get that response because we came in from the bottom and now we’re at the top and keeping it at the top,” Silvia said.

Union City is right across the river from Manhattan — just a 20-minute drive from Times Square. It’s a dense community filled with many recent immigrants, a lot of whom live below the poverty line. Many students don’t speak English at home.

“Some of the challenges that our students face are huge,” Silvia said. “You don’t expect these children to be as successful, which is a terrible thing to actually say. But because of the school system and the community and the support from the community, they make it.”

And many do more than just make it.

The district’s graduation rate is on par with the rest of the state, and many students go on to earn college diplomas, some from the most competitive colleges and universities in the country.

Silvia strongly believes in public education as the “great equalizer” and said her district has been able to deliver on that promise thanks to adequate funding from the state.

“There’s a way out of poverty, and it’s called education.”

‘Improbable’ success in Union City

Silvia Abbato and her twin sister Adriana Birne understand the challenges their students face in a deeply personal way. They grew up here and have spent their entire careers in the district — more than 40 years each.

Like many of their students, Silvia and Adriana are immigrants. When they arrived in Union City from Cuba at 9 years old, they didn’t speak English, and the district didn’t have much of a program for English learners back then.

Despite the challenges they faced, Silvia and Adriana made it through and decided to become teachers just like their parents, who taught in Cuba and later in the United States.

Things have gotten better since then. Today, the district offers comprehensive bilingual education, including a gifted program. Students who don’t speak English learn in their native language so they don’t fall behind in their coursework. Once they become fluent, they move into English-only classrooms.

When the sisters started teaching in Union City’s schools straight out of college, the district’s buildings were in disrepair. Silvia says she covered holes in the walls with posters.

“Those are the things that you did because you didn’t have the facilities,” she says.

It was issues like these that inspired a famous school funding lawsuit in New Jersey, Abbott v. Burke. (Though it was filed in 1981, it’s very similar to the one plaintiffs in Pennsylvania just won.)

The case didn’t result in instantaneous change, and the long-term results aren’t perfect. But with time and many returns to the court over the course of decades, more funding started to flow to schools in need.

New Jersey’s Supreme Court said the state had to invest more money in poor urban districts to ensure students had access to the same standard of education as children in wealthier suburbs. Not only did the state have to send these districts a lot more money, but it also had to cover 100% of their eligible construction costs.

The court also required the state to pay for two years of full-day, high-quality preschool for students in districts covered by the Abbott lawsuit.

Silvia says this means children in Union City leave kindergarten reading and writing, which was unheard of before preschool education was mandated in some New Jersey districts.

The district has an entire building dedicated to early learning, complete with the latest technology, an aquarium in the lobby, and elaborate decorations. There are life-size trees and flowers made out of craft paper that make the hallways feel like Disney World.

District director of early education Adriana Birne says the decorations aren’t just fun — they also demonstrate a high standard of learning. There are projects that show off students’ handwriting to their critical thinking skills.

Silvia is always looking to expand what students are learning. When she found out schools in the suburbs were teaching Mandarin, she started a program in Union City’s schools.

“So the little ones will leave early childhood speaking Spanish from their home, English from the schools, and Mandarin,” she says on a tour of the building. “How beautiful is that?”

Steve Barnett, an early education researcher who served as an expert witness in both New Jersey’s and Pennsylvania’s school funding trials, says the money from the Abbott rulings has resulted in one of the best preschool programs on the planet.

“The city council from Oslo, Norway, came to New Brunswick, New Jersey to learn about educating immigrant kids,” he said.

Barnett says the success of New Jersey’s preschool program, which he helped shape, comes back to how the program was designed.

“Often it’s because the standard operating procedure is to begin with the budget and work your way backward,” Steve said.

This time, it was the other way around.

Mandated by the court, the state handed the reins to early education experts to design a program without worrying about the price tag. That meant they could actually implement research-based practices.

They started by capping classes at 15 students, and staffing each room with a lead teacher and an assistant.

The head of the newly formed department was another respected researcher, Ellen Frede. Today she co-directs the National Institute for Early Education Research at Rutgers University with Steve. The two are also married.

“I was so lucky,” she says. “In a sense, money was no object, but we weren’t going to be stupid about it. We didn’t put anything in that we couldn’t justify in the research.”

School districts didn’t have the capacity to create preschools out of thin air, so they partnered with programs that already existed that were willing to rise to the state’s high standards. And for the most part, they did.

To this day, in the rest of the country, all of this is still pretty much unheard of. Even though the benefits of high-quality preschool are well known.

“I don’t understand why any state would not want to invest in early childhood to make sure kids don’t enter the kindergarten door a year or two years behind,” Steve said. “Why play catch-up?”

He says if Pennsylvania wants to respond strongly to its court ruling and get kids on the right track, it has to invest in early education.

“You don’t have to invent it. It’s right next door.”

An imperfect solution

Nobody knows the bumpy road to more school funding better than David Sciarra, the former head of New Jersey’s Education Law Center.

He was the lead attorney for the plaintiffs in Abbott v. Burke, which originally included 20 schoolchildren from Camden, East Orange, Irvington, and Jersey City.

David took over the case in the 1990s from the center’s former head. In the years that followed, he went before the state’s Supreme Court over and over again to make sure lawmakers followed the initial ruling — which said Abbott districts had to be funded on par with wealthy suburban districts and have the money to provide additional resources for children from families who live below the poverty line.

Since Abbott was first filed in the 1980s, New Jersey’s Supreme Court has issued 23 orders clarifying and expanding on that initial ruling.

He said it was important not to look at funding as a zero-sum game. The goal wasn’t to redistribute resources from wealthy to poor districts.

“One of the important messages we were always trying to make was that this was not going to be a Robin Hood situation,” David said.

The plan was never to pool all the money from local property taxes and divide it up.

“This was essentially lifting up the poor districts to what they needed. It wasn’t going to be winners and losers.”

The problem was (and still is) that even with the state pumping more money into the system to help poorer districts catch up, there remains an underlying issue: relying on local property taxes to help fund schools.

Since New Jersey and Pennsylvania have significant economic inequality between school districts, property taxes are an inherently inequitable way to pay for schools.

“It happens to be that New Jersey compensates for that really hard with very high levels of state investment — and it’s still not catching up,” said Zahava Stadler, who works for the public policy think tank New America, where she studies equity in school funding.

While the money awarded to poor, urban school districts brought spending up to the level of suburban schools (and in some cases beyond), Zahava says those increases haven’t been sustained.

As a result, the gaps between high- and low-wealth districts have opened back up. And Zahava says Pennsylvania doesn’t want to find itself in the same position.

“The ground-level inequalities are too big for states to constantly try to fix them only by pouring state money into the hole,” she said. “That money is going to run out. And when states hit recessions, the districts that are most at risk are the highest poverty, lowest wealth districts that depend most on state help.”

That means the system is set up to fail the neediest in hard times, according to Zahava.

“Ultimately, this is all a policy choice, and it’s a policy choice that state legislators are making or a policy choice that state legislators are declining to make.”

The United States has traditionally relied on local property taxes to fund schools as a country, but Zahava says it doesn’t have to be this way — and some states have decided to do things differently.

That includes Vermont, which has more of a Robin Hood-esque situation where wealthier towns pay higher property tax rates to subsidize schools in poorer areas, and Kansas, where the state caps how much districts can spend, preventing gaps from forming in the first place.

Pennsylvania and New Jersey don’t do that.

Meanwhile, Zahava says in both states, the wealthier suburbs are moving the goalposts for everyone.

“They have changed the definition of how much is enough for my education because we’re applying for the same state university spots, we’re applying to the same jobs on graduation,” she said. “Ultimately, they’re redefining enough for all of us because we occupy the same society.”

David Sciarra, the lawyer for the plaintiffs in Abbott vs. Burke, says he knew that asking the state to fill an ever-growing gap wasn’t the best solution, but it was the one they had based on the court’s ruling.

“We all always want a quick fix. Have test scores gone up from one year to the next? It’s the wrong question,” he says. “The question is, ‘Is the state leading the effort to make progress over time from year to year, from even decade to decade?’”

While the money from New Jersey’s court decisions led to transformational changes in Union City, that hasn’t been the case for all of the plaintiff districts. Some have shown more modest progress, while others haven’t shown much progress at all.

Overall, New Jersey has some of the highest test scores in the country today, and some credit added funding from the Abbott decisions for that. But there are still large achievement gaps between children based on race and income.

“So what does that say? It doesn’t say that we shouldn’t do it,” David said. “The kids are entitled to it. The state has an obligation to provide it.”

But it takes more than just money to move the needle. You need political support. Union City’s long-time mayor is a champion for its schools and committed school leadership, like sisters Silvia Abbato and Adriana Birne. The district is known for its continuous improvement model. It’s constantly adapting and teachers receive regular feedback.

Silvia likes to stay ahead of the game, so she keeps her eyes on two things: How is her student body changing, and what does it need? She also keeps tabs on changes happening in the suburbs, because she wants her students to have the same opportunities.

“We’re not going anywhere,” Silvia says. “We care about the community. We built this foundation and we want to see it through.”

A question of ‘political willingness’

David Sciarra says Pennsylvania can learn a lot from what’s happened in New Jersey in the more than three decades since the first Abbott ruling.

“We know how to fix these things, he said. “It’s a question of political willingness.”

David says the state’s governor, Democrat Josh Shapiro, needs to think “outside of the box” and look beyond one budget to the next.

If he doesn’t, David says generations of students could be affected.

“He has to step up,” David said. “If he doesn’t lead, this opportunity is going to be lost.”

In response to the state’s landmark court ruling on school funding, Shapiro promised a “significant down payment” for schools in his first budget address in March.

“We are all acknowledging that this court has ordered us to come to the table and come up with a better system — one that passes constitutional muster,” Shapiro said. “It will take all of our ideas for not just how many dollars we set aside from the state for public education, but how we drive those dollars out to local districts adequately and equitably.”

But the actual numbers in his proposal left some disappointed.

Public education advocates said the governor’s proposed increases do little more than keep up with inflation. And they balked at his decision not to increase the amount of money sent to the state’s 100 poorest school districts.

Some chalked the proposal up to the political process, arguing Shapiro had no choice but to start with a lowball. The state House passed a budget bill earlier this month that would add $625 million more for education on top of the roughly $800 million increase in Shapiro’s proposal. The bill includes an additional $225 million for the state’s most underfunded school districts.

While some Republicans say that level of spending is astronomical (the bill passed without any GOP support), funding advocates argue it’s affordable since the commonwealth is sitting on billions of dollars in surplus and reserves.

For the funding to make it into the coming budget, it needs to clear the state’s GOP-controlled Senate and the governor’s desk by June 30.

Setting a baseline

Before Gina Curry was elected to the Pennsylvania state House a year and a half ago, she was a school board member in Upper Darby, an underfunded school district in Delaware County.

Back then, she would come to the Capitol every few months to meet with lawmakers and ask them for more money. Now, she’s the lawmaker being asked.

Rep. Curry says she’s trying her best, but the political process is overwhelmingly slow, and divisions run deep in Harrisburg.

“How many times have people come up here, been on the steps, given their testimony? How many meetings do we have to say, ‘This is what we’re going through?’” she said during an interview in late April.

“I just don’t think everybody is in agreement that what’s happening is really happening.”

While some districts have more than enough resources, others, including the ones Curry represents, are struggling.

“There’s never going to be real kumbaya moments for situations like education because everybody has their own opinion about how it impacts their community,” she said.

Since the court ruling, Curry said the conversation has shifted. Most people understand the system has to change, but not everyone is on the same page.

There are legislators who say they support more equitable school funding, but don’t always make good on that promise when it’s time to vote on policies because they’re afraid the schools in their legislative districts may lose money.

“The reason that fear is there is because it’s justified. That is the current system,” says Rep. Jesse Topper, the Republican chair of the House Education Committee.

WHYY News asked to speak with House GOP leader Rep. Bryan Cutler, one of the Republicans named in the school funding lawsuit, but he declined and told us to speak with Rep. Topper instead.

“I think what Republicans and Democrats can agree on is that access to a high-quality education should not depend on your ZIP code,” said Topper.

He also believes that Pennsylvania needs to set a funding baseline to make sure schools have what they need, and if a district wants to go beyond that it’s up to them.

Topper says in the world of education, there will always be haves and have-nots — some students will have access to Olympic-sized swimming pools and state-of-the-art basketball arenas, and others won’t.

“That’s fine. I’m OK with the local tax base determining those kinds of things,” Topper said, because life isn’t fair.

“It’s the important lesson that my dad always taught me. Whenever I said something wasn’t fair, he said, ‘Son, the fair comes once a year and it’s not today.’”

But even if no one expects all schools to end up with the exact same things, it’s hard to determine what the funding baseline should be.

Rep. Gina Curry said the situation is complicated because schools in her community, like Upper Darby and the William Penn School District, have long been deprived of money for basics. Many of their school buildings are in disrepair and children have far fewer academic and extracurricular options than children in other wealthier districts.

“We’ve already lost and we’re at the start with everybody else,” she said. “Until we can get prepared, boosted up, ready for the race, we’re going to come in last.”

Shapiro said he expects bipartisan support on a solution that gets more money to low-income schools.

“What we now need to do is come up with a formula that drives dollars out where the need is and increases the pot of dollars that go to those schools,” Shapiro said at an event with Philly business leaders in May.

That pot is state money, and it’s an important part of school funding, especially for property-poor districts that have a hard time raising their own money.

Most states use formulas based on enrollment and other factors to drive state dollars out to schools. Experts say Pennsylvania has a pretty good formula already since it also takes into account the amount of money districts are able to raise locally, and the fact that some kids are more expensive to teach than others. The glaring issue, they say, is that most education funding doesn’t stem from the formula. Because when it was passed in 2016, lawmakers decided the formula would only apply to newly allocated dollars.

“Which means that all the state can do is really put some nice new icing on top of the existing unequal cake,” said Zahava Stadler with New America. “Ultimately, when you bake in all the preexisting inequality, there’s not a lot of room to work.”

For example, about a quarter of the state’s total basic education funding this coming budget cycle is expected to be distributed using the formula under Shapiro’s initial proposal. That means the vast majority of funding isn’t distributed based on current needs, but instead on decades of politics.

Shapiro says his goal is to revise the formula in time for the state’s next budget cycle one year from now. To get this done, the state reconvened last month the commission that created its existing formula.

Rep. Mike Sturla, the commission’s Democratic co-chair, says his goal is to update the formula and make sure it’s fully phased in within five years. He expects things to be different this time because of the court ruling.

“It’s a pretty big hammer hanging over our heads,” he said.

That hammer is the fear of ongoing legal action and more prescriptive rulings from the court, like what happened in New Jersey. Sturla said even lawmakers who favor change, like himself, want the freedom to come up with a solution without continued court involvement.

“I, for one, am happy to have that hammer hanging over our heads,” Sturla said. “I’m now feeling like maybe within my lifetime I will be able to see adequate and equitable funding.”

‘Do more with less’

While Rep. Gina Curry works on securing more funding for her schools in Harrisburg, 100 miles east, her husband Rap Curry is feeling the effects of the issue directly as the athletic director for the William Penn School District.

Coach Rap, as his students call him, has worked at the high school for more than two decades, and was a key witness for the plaintiffs in the school funding trial.

He points out a loose gravel track on a tour of the high school’s athletic facilities. It’s the kind that used to be prominent at playgrounds near swings — not the rubbery turf often seen at modern running tracks.

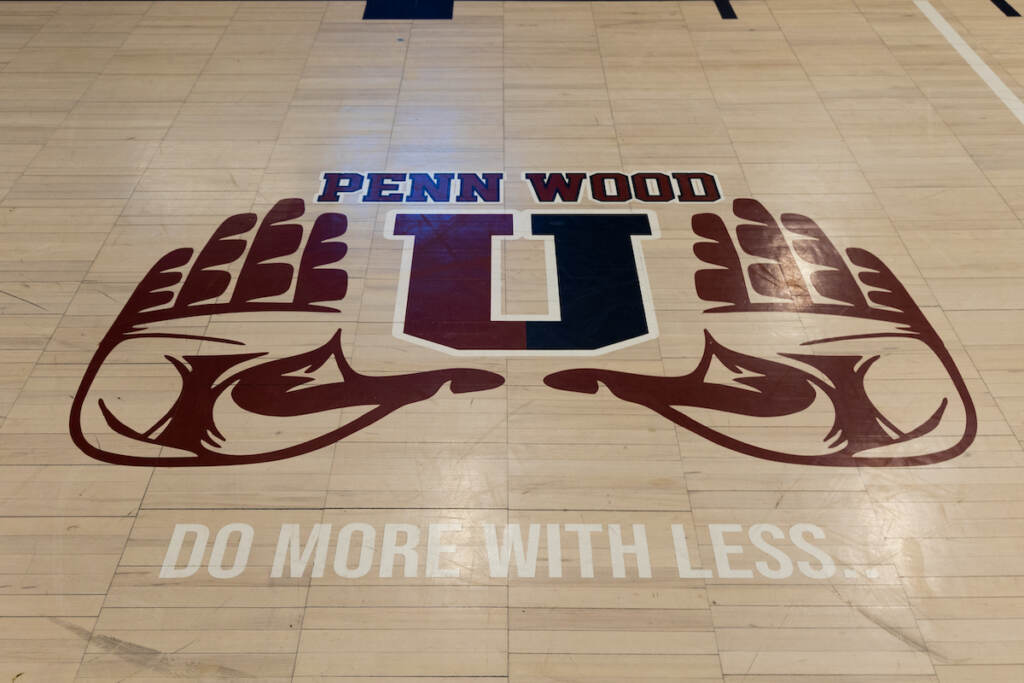

“We can’t really play where we’ve been playing,” Coach Rap says. “I use a concept called, ‘Do more with less.’”

It’s become Coach Rap’s slogan. He even managed to get it printed on the gym’s floor.

“Yeah, I snuck that in here,” he said with a laugh.

He had to sneak it in because not everyone likes the language. Some people worry the expression can make students feel inferior, or that it can be used as a cop-out for underfunding schools and maintaining the status quo.

Coach Rap does not believe in the status quo.

William Penn’s football field doesn’t have lights. Coach Rap couldn’t afford to buy them, so he came up with the money to rent portable ones so the team could play games on Friday nights.

He says having home games had a huge impact on his players and the community. And though it’s not a perfect link, Penn Wood’s team did go on a winning streak.

“We went from like a team that won no games to being the number one seed in the district,” he said with a smile.

When William Penn Superintendent Eric Becoats arrived in the district a few years ago, he kept hearing about how terrible the facilities were. So he had each school assessed, ranked the projects based on urgency, and came up with a 10-year plan.

Athletic facilities made it to the top of the list.

“I think it is essential because [for] some students without athletics, I don’t know if they would get up and come to school,” he said.

Construction is underway on a more than $14 million athletic complex that includes a new turf field, synthetic track, baseball and softball fields, locker rooms, concession stands, parking, and restrooms — things many suburban school districts already have.

“The athletic facility is a classroom. Students are learning. They may be learning different things, different ways, but they are learning.”

For this project and others, the district is lining up the money as it goes.

Superintendent Becoats says he’s been aggressive about applying for grants from the state (the district recently received $7 million) and the federal government.

But the community is also taking on debt. The district recently took out a $10 million bond to pay for the athletic complex and other building repairs. In all, the decade-long project is expected to cost more than $160 million to complete. While that is a hefty price tag, Becoats said he believes in investing in yourself and your community.

“There were some people who said, ‘How are we going to pay for this?’ And I’m one of the folks who believe, you know, you don’t say no to yourself,” he said.

Becoast says you have to try.

“I believe that you have to develop a plan, set your vision, tell people what you are about, and then work toward trying to achieve it.” Not trying, Becoast says, is “borderline insanity.”

Even though the recent court ruling is promising and could steer money toward districts like William Penn, Becoats isn’t counting on it.

“I am hopeful that the state will respond and do what it is supposed to do,” he said. “But do I sit here thinking, OK, when is it coming? When is it coming?’ No, because my focus has to be on putting things in place.”

‘You are deserving’

Teacher Nicole Miller’s kindergarteners have gone home for the day, but her classroom at Evans Elementary, an underfunded school in the William Penn School District, isn’t empty.

Her kids are with her. There’s her 18-year-old daughter Nyla, her 15-year-old son Marion, and her 11-year-old McCaury.

They all go to school in her district, and Nicole loves that she gets to share her world with them.

“You find across the district that a lot of us have come back,” she said. “It just feels like family.”

She values the close-knit community, but she knows if her kids went to school in another district — even one just a few miles away — they would have more opportunities.

“You know you want to give your kids the best,” she said, choking up. “I get emotional.”

She turns and asks them a question that’s been weighing on her.

“Would you want it different? Would you rather go somewhere where there are more resources?”

“Absolutely not,” said Marion. “I wouldn’t change a thing. This is my home.”

Nyla comes over and wraps her arms around her mom. She agrees.

“The one thing that we have that I don’t believe other districts have is the source of love and family,” Nyla said. “I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else because I know nowhere else could produce that, ever.”

Nicole lets out a sigh of relief.

“I’m glad to hear that because that’s how I feel,” Nicole said. “You often wonder, ‘Am I doing the right thing?’ I want to be here. I want to help be a change agent, but is it at the cost of my kids? Do they feel like they’re less than others because they see other places that have more? I try to talk to them at home, ‘Like that’s not what that means. You are deserving.’”

And for more than 20 years, Nicole has taught her kindergarteners that lesson too.

It’s the same one Coach Rap is trying to communicate to his athletes, even as he tells them to do more with less, and the example Superintendent Becoats is trying to set by going big with construction instead of holding back — that their children, and all children in Pennsylvania, are deserving.

They’re hopeful the court ruling forces others to see that. And that eventually, the money will come.

Become a WHYY Passport Member

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.