They saw ESL classes as a key to the American dream. Here’s how they adapted through COVID

Adults learning English as a second language take classes in libraries, schools, and churches, but when the pandemic hit, all those places closed.

Andrea Miron of Bridgeville writes on a marker board during an English as a second language class at the Georgetown Public Library Thursday, July 22, 2021. (William Bretzger/The News Journal)

When COVID-19 took hold and society started to shut down in March of 2020, hundreds of Latinos in Sussex County, Delaware, worried it would delay their American dream.

Specifically, they worried about achieving their goal of learning English.

An important tool in reaching that goal was the English as a Second Language program.

Many Latino adults join the program as a step to finding a job, enrolling in school, obtaining a driver’s license, or improving their ability to communicate with their children’s teachers.

The programs — usually conducted in libraries, schools, and churches — focus on grammar, reading, vocabulary, writing, and conversation.

But when the pandemic hit, all those places closed.

Not wanting to shut down completely, some ESL programs went strictly virtual, using Zoom, starting in April 2020.

Within a month, the separate programs started working together at the urging of La Colectiva, a network of nonprofit, governmental, and for-profit organizations in southern Delaware that works collaboratively to address needs of Latino families. Coordinators from eight programs created their own ESL Network. They began meeting regularly to develop working relationships, find ways to adapt their programs, and support their teachers and students through the challenges of COVID-19.

The transition was difficult at first, since most of the students did not have access to computers at home.

Many students used their smartphones, which limited how they could participate in class activities.

“Learning from a phone is more difficult than seeing a blackboard,” said Betty Kirk, program director at Unitarian Universalists of Southern Delaware in Lewes.

In some areas of Sussex County, internet connections are less reliable, resulting in slow or choppy audio and video responses. Instructors said that classroom interaction is tough to replicate on Zoom.

They also said many adult students are not tech-savvy and found it difficult to log into Zoom or use it.

These issues hindered participation in the classes for some students.

Pam Cranston, program director at the Lutheran Church of Our Savior in Rehoboth Beach, one of the largest ESL programs in Sussex, surveyed her students, asking them why they were missing classes. About 30% cited job issues, 20% mentioned family issues, and 15% said health issues interfered with their attendance. Technology problems were also a factor: 7.5% said their devices were not working, and 5% said their internet connection was bad.

But the transition to online classes appeared to increase the number of people enrolled, possibly because fees are lower for online learning, Cranston said.

Greg Hitz, a volunteer teacher at the libraries in Lewes, Georgetown, and Milton, said “participation hasn’t changed much pre- and post-COVID, and may actually be higher now due to this lower cost.”

Most onsite classes are free, but adults have to pay $25 to $30 for their textbook. For online classes, there is no textbook.

Some program directors believe charging for the workbook will motivate the student to come to class since they paid for it.

“Adults didn’t have a hard time financially with the program,” said Kirk. “Sure, you save money on gas and fees charged on workbooks, but there is nothing like learning in-person with hands-on experience.”

When Cranston and her staff asked their students if they would rather stay on Zoom, a little more than half said yes.

“As time went on, many students started to like Zoom once they gained more knowledge on how to use it,” she said.

But the switch in learning modes created an unanticipated problem, Cranston said. Students adapted better than the instructors and many teachers left the program.

Teachers either couldn’t concentrate with their children at home or felt it was too difficult to teach online.

“Finding teachers was the hardest thing to do during COVID,” said Cranston. “But we made an adjustment by looking for teachers in Maryland.”

Being fully remote opened more opportunities for potential volunteer teachers. It turned out to be a blessing in disguise.

Other programs also adjusted. Literacy Delaware, which is based in Wilmington but expanded its ESL program to Sussex County, initially struggled to find students in Sussex.

In June 2021, the organization hired Dale Ashera-Davis to be program coordinator.

She was tutoring at the Frankford Library and decided the best way for the literacy program to move forward was for all the Sussex libraries to work together.

Davis connected with three library directors and with La Colectiva’s ESL Network. From there, more ideas to improve more ESL programs emerged.

The communication between the libraries brought in new resources and enabled them to give Chromebook laptops to students who needed them.

This helped students who had previously been attending class on their phones.

“Everything has been because people work together in cooperation, we do not lose sight of the people we serve,” said Davis.

The libraries coming together also led to more students signing up. One of those students was Kevin Fuentes.

Fuentes, 31, was born and raised in Puerto Rico and moved to Delaware three years ago.

Not knowing any English, Fuentes struggled to find a job.

“I did a lot of thinking during the pandemic and realized I can better myself in this country if I learn the language,” he said.

He didn’t know there were English classes and asked his coworker how he could learn English. “My friend Ulisses heard about the program in a library, and I said, ‘Sign me up,’” recounted Fuentes.

Like most language-learners, Fuentes struggled in the beginning, but was able to hold a conversation in English within months. Now he can speak, read, and write in English on an intermediate level.

He loves being online because he lives in Seaford and would rather not travel 40 minutes to classes at the Frankford Library.

“I would’ve had a major transportation issue,” said Fuentes.

Davis is proud of how far Fuentes has come. She said he’s one of her star students.

While recovering from the pandemic’s impact, almost every program has experienced highs and lows. Some of the most significant lows were felt in the program run by the Sussex Technical School District.

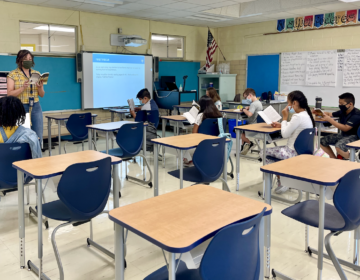

Pre-pandemic, Sussex Tech had more than 400 students a year in its English program, offering classes four days a week. When COVID hit, enrollment dropped 60%, in part because teachers weren’t accustomed to working on Zoom, according to Linda Eklund, Sussex Tech’s director of adult education.

Finding teachers was difficult, but Sussex Tech had a plan that would help its teachers adjust and learn how to teach on Zoom.

“The first couple of weeks during COVID were tough,” said Linda Tuttle, who teaches at the Georgetown Library location for Sussex Tech. “I’m an old dinosaur, so the new technology was difficult for myself but … [the] trainings made it easier for me to learn quickly.”

When enrollment dropped, Sussex Tech quickly adjusted its class groupings. There weren’t enough students to group by ability — beginner, intermediate, and advanced — so they were mixed.

“It’s difficult when everybody is on different levels, but they all help each other,” Tuttle said. “My best student will help my beginner student and my middle student uses my best student as motivation to move up levels.”

Andrea Miron is Tuttle’s best student. She will be graduating from the program.

Miron is 30 years old and joined the English program in September 2020 to find a better job and better communicate with her two children.

She wants to be a role model for her kids. Miron doesn’t yet know what her own career goal is, but wants to be able to pay for college for them in the future.

“It was easy for me because I have a great teacher and the program was so hands-on,” Miron said. “I was able to learn English in less than a year.”

___

This article was produced with the support of a grant from the Delaware Community Foundation. For more information visit https://www.delcf.org/journalism/.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)