‘They didn’t have proper PPE’: These Black health care workers got the vaccine. They say distrust isn’t just historical

Lack of proper protections at the pandemic’s start eroded these Black health workers’ trust in medical systems. But they’re still getting vaccinated.

Listen 1:56

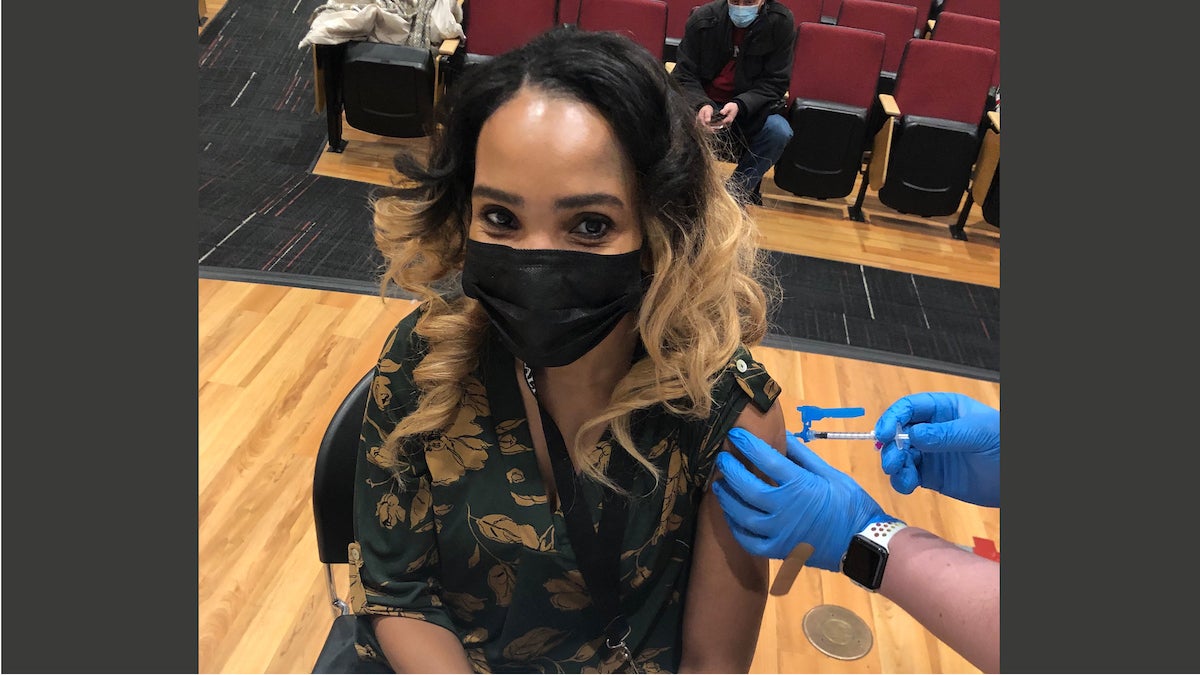

Keta White is a health care worker in Philadelphia’s Mt. Airy neighborhood. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Ask us about COVID-19: What questions do you have about the coronavirus and vaccines?

Keta White is a Black health care worker at Germantown Home, in Philadelphia’s Mount Airy neighborhood. And she’s one of 13,000 members of District 1199C, a majority Black- and brown-led union that represents Black workers in all fields in the major health care institutions in the city — behavioral, mental health, and child care facilities, as well as employees who provide health care services within the city’s prison systems.

At White’s nursing home, she works in the laundry department, sorting and delivering personal clothing to residents. Typically, Germantown Home accommodates 180 beds, but she said that at the height of the pandemic, 60 residents passed away after contracting the virus, one-third of the home’s elderly population.

“We were very close to the residents, very close,” White said. “Some of the workers had to take a leave because it was just so overwhelming seeing the residents pass away daily and their family members not being able to be there for them.”

Chris Woods, president of District 1199C, said experiences like White’s prompted many members of the union to leave health care altogether. Over the course of the last several months, he and other union officials have worked with employers to ensure that members have proper PPE, hazard pay, and equitable hours. But the pandemic’s devastation left a lot of his membership afraid, Woods said, and there’s been a lot of concern about the efficacy of the vaccine as well.

“We did a survey before the vaccine rollout, and many of [our union members] indicated to us that they needed to have more information about the vaccine before taking it,” Woods said.

District 1199C has partnered with health care employers in the city to get union members vaccinated at their places of employment. Woods said the union is hosting a series of virtual information sessions online, to which physicians and other health care professionals are invited to talk about the vaccine’s safety and efficacy.

White remembers when seniors in her nursing facility started to get sick with the virus, and the anxiety that came over the workplace as they tried to manage the growing number of infections. Then a coworker and dear friend of 25 years contracted COVID-19 and died. That loss was the toughest, White said. Several months later, the union was offering the vaccine to her and other employees at the nursing home, and her immediate reaction was skepticism.

“I said let me consult my doctor first because I have chronic bronchitis and respiratory problems,” White recalled. “And he said most definitely take it, so Feb. 6 I took my first dose, and Feb. 16 I took my second.”

The weight of all the loss she had to witness on the job this past year ultimately drove her to get the vaccine, White said. And after her first dose, she felt a sense of relief pass over her.

“[I thought] maybe this vaccine will bring us back some kind of normalcy, so I just felt like I had to take it,” White said.

Aside from a sore arm moments after being injected with the vaccine, she had no side effects at all. She feels very confident that the vaccine is safe, that it works, and now she’s encouraging friends and family members in her own circle to take it.

“A lot of people think the vaccine is just made up, like they just invented it,” White said. “But I tried to explain to them that this was being prepared when Obama was in office, when we were going through other [epidemics] like Ebola.”

White was referring to the Obama administration’s investments in mRNA vaccine research, which contributed to the record speed at which doctors and researchers developed COVID-19 vaccines. Last July, at a hearing of the House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis, U.S. Rep. Bill Foster, an Illinois Democrat, highlighted this contribution.

“Heeding the advice of his scientific panel, in 2013 the Obama administration invested $25 million through DARPA for research into the mRNA platform for pandemic response … so that by the end of the Obama administration, mRNA vaccines and therapeutics were being tested in both animals and humans,” Foster said.

“Without those kinds of investments, ‘Project Warp Speed’ and current efforts to produce an effective COVID-19 vaccine as quickly as possible would not be finding success.”

‘We need Black physicians at the forefront…’

Woods, of District 1199C, said a lot of vaccine hesitancy among the union’s membership was fueled primarily by the lack of adequate protection and pay employers were willing to give at the outset of the pandemic.

“[They] didn’t have proper PPE, folks weren’t paid hazardous pay, and some of these COVID units that our folks were assigned to just weren’t safe,” he said.

In the beginning, Woods said, he had a large segment of health care workers who were not eager to return to the job because proper safety precautions weren’t in place. Then, when the vaccine rollout started, they were being asked to opt into taking the vaccine without proper focus on vaccine education. By that point, many union members had lost trust in the health care institutions that would eventually be responsible for vaccinating them. Woods noted that two major employers tried to mandate vaccination for work eligibility, a policy they eventually retracted.

Fatima Cody Stanford is a physician at Harvard Medical School. In February, she co-wrote an article in the New England Journal of Medicine entitled “Beyond Tuskegee — Vaccine Distrust and Everyday Racism.” Stanford said that on top of the everyday racism Black Americans face in health care, Black people across industries typically are not receiving vaccine education from other trusted, Black health care professionals — and that’s really significant.

“We need Black physicians and investigators at the forefront of vaccine-rollout efforts,” Stanford wrote. “Black scientists sharing their stories is paramount because they can more directly relate and speak to their communities’ needs.”

An NAACP study found that Black Americans were twice as likely to trust a messenger of their own racial/ethnic group than one from outside it.

“When trust is in short supply everywhere, we need all hands on deck to begin rebuilding trust in health care. We believe the best way to learn from the atrocities of the past is to change our present.”

‘My daughter got it, then I can get it too’

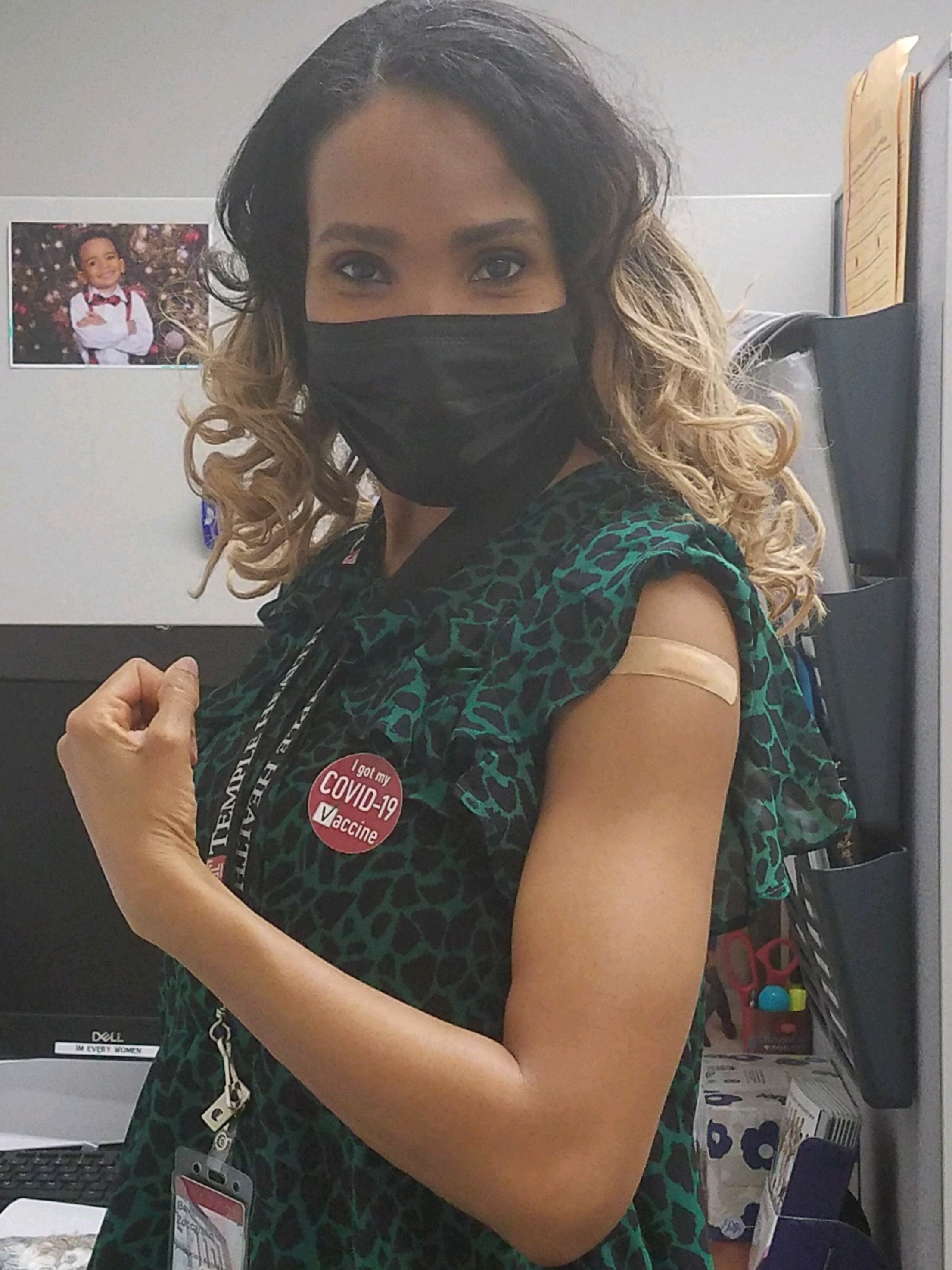

Beverley Zuccarello is a Black physician assistant at Temple University Hospital in the GI department. She was vaccinated on Feb. 17 and says that though her job gave her adequate knowledge about how the vaccine works, that’s not always the case for everyone who works in health care. That’s particularly true for employees like White, and for much of the general population who work in non-medical capacities. Zuccarello recalled several conversations she had with her parents over the dinner table about their COVID-19 anxieties.

“Between my husband and I, we’re both very scientific people, and we go by data and not by what people are saying,” Zuccarello said. “So it was just [my parents and us] talking over the dinner table saying, ‘You know, it’s not a live vaccine, everything in there is synthetic.’”

After much back-and-forth with her parents, they took an interest in learning more about the vaccine. And Zuccarello said the ultimate game-changer was getting the vaccine for herself and proving to them that it left her with very few side effects. Her parents were one of the many Philadelphians who wrapped around Temple University’s Liacouras Center during the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium’s first 24-hour vaccine clinic on Feb. 20.

“I think that that showed them that, you know, it’s something that’s safe because ‘my daughter got it, then, you know, I can get it to,’” Zuccarello said.

For White, the best part of her job is putting a smile on her client’s faces. She’s been a health care worker for over 15 years and said the pandemic has really affected her ability to connect with patients in-person. Now, there’s a floor at her nursing home just for patients who have COVID-19. When she goes to that floor, she has to be covered head to toe in PPE, she said.

Now, she’s just telling anyone who will listen to get the vaccine: “I’m literally begging, please get it.”

—

Support for WHYY’s coverage on health equity issues comes from the Commonwealth Fund.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)