The Library Company looks back at its Imperfect History

“Imperfect Histories” revisits visual, racial, and gender bigotry going back hundreds of years, both intended and unintentional.

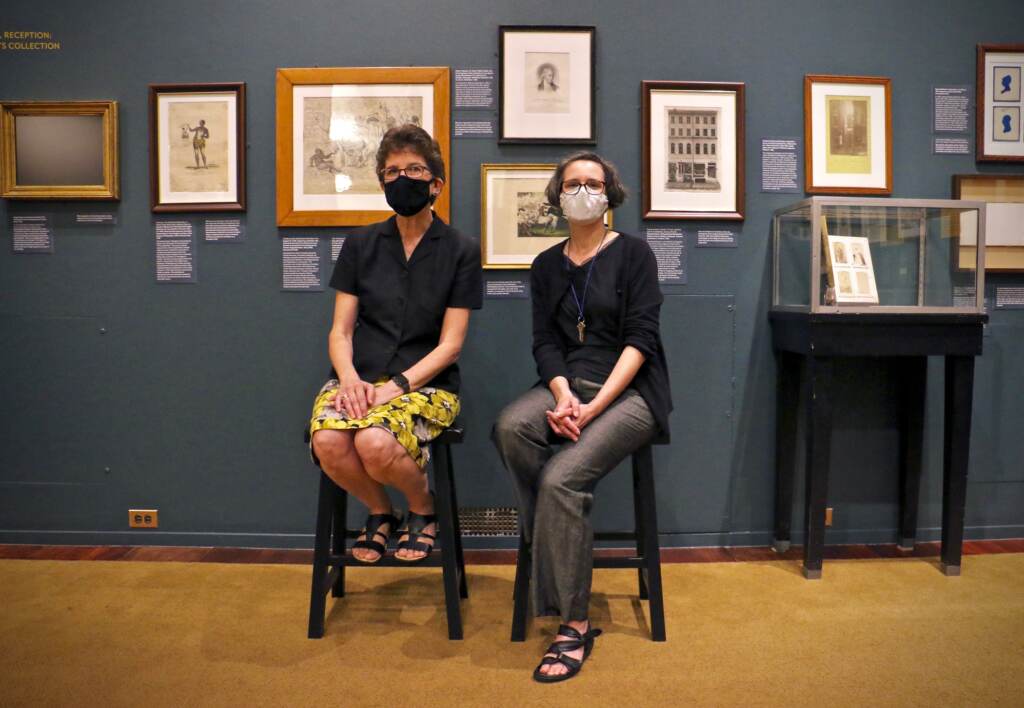

More than 100 objects dating from the early 1700s are displayed in the Library Company of Philadelphia's exhibit, ''Imperfect History,'' which examines the role of graphic arts in preserving and distorting history. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

The Library Company of Philadelphia is the oldest lending library in America, and also its oldest cultural institution, founded in 1731 by Benjamin Franklin, among others in Philadelphia.

Created primarily as a repository of books and manuscripts, it always had graphic art items – illustrations, etchings, and eventually photography – but never took them seriously until relatively recently, in 1971 when the library created a graphic arts department to inventory, catalog, and conserve the paper-based imagery that had been literally piling up on open shelves for 240 years.

The Library is now marking the 50th anniversary of that department by showing off its imperfections.

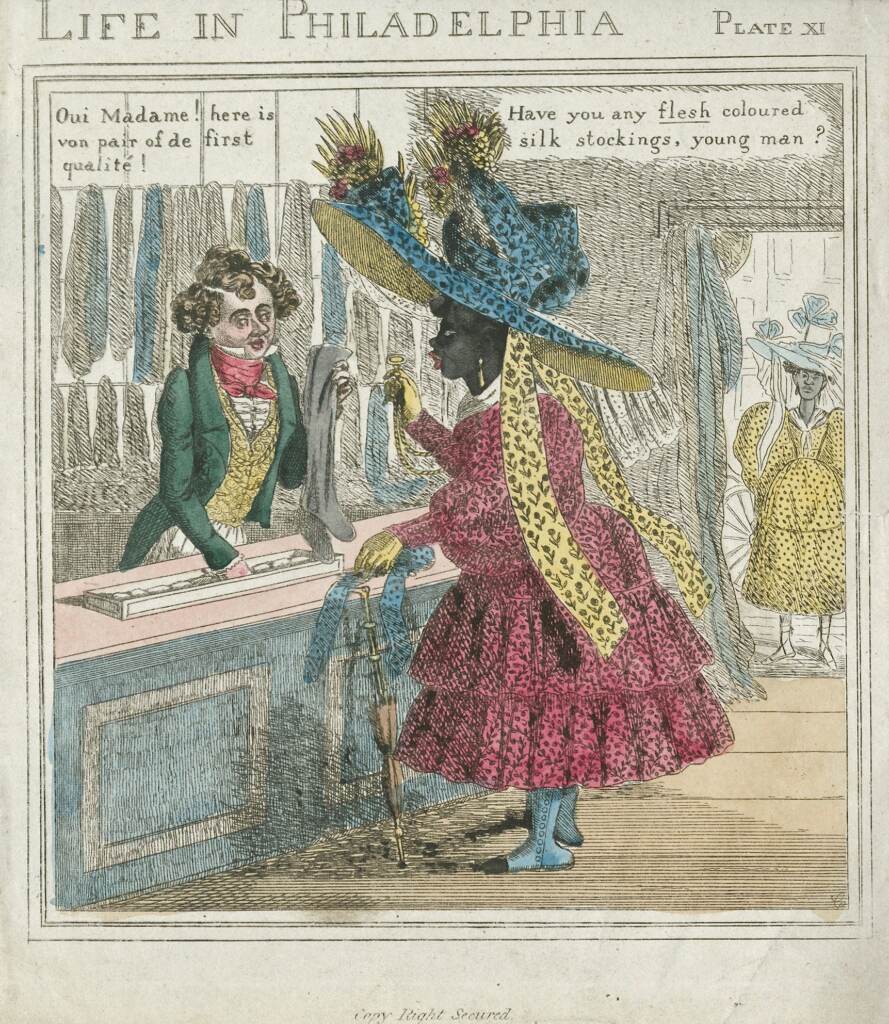

“Imperfect History” does double duty. One thing the exhibition does is show visual, racial, and gender bigotry going back hundreds of years, both intended and unintentional.

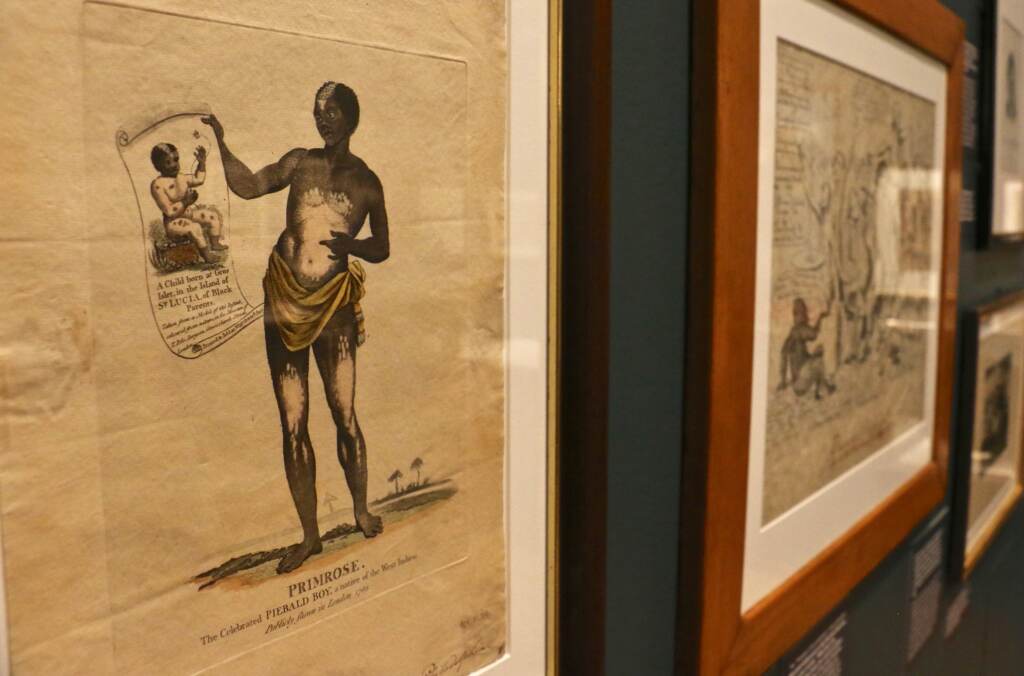

Case in point is a print of “Primrose: The Celebrated Piebald boy” (1790) published by Thomas Pole, a Philadelphia expatriate who had a long and successful career in England as a physician. The image is of a Black teenaged slave from the West Indies named John “Bobby” Primrose, who had piebald, a condition that turned portions of his skin white, similar to vitiligo.

Although based in London, the drawing shows Primrose wearing a primitive loincloth – to best display as much of his skin as possible – set in a landscape with palm trees, evoking his West Indies origin.

“This is not only a portrait of Bobby, but it’s also an advertisement because he was going to be put on display as a medical curiosity at Pole’s anatomical museum,” said Erika Piola, the library’s Director of Visual Culture.

Although Pole was not a member of the Library Company, he donated this print in 1799.

“He was thinking of the library as an archive of scientific and medical information at that time,” said Piola. “It’s a print that’s very much influenced by the scientific and racial biases of the late 18th century. That plays into the role of the Library Company as an agent of those racial and scientific biases of that period.”

The second thematic pillar of “Imperfect History” is showing the Library Company’s institutional imperfections throughout its nearly 300-year history, and how it evolved its own visual literacy over the years.

As an organization founded with its focus on books and written material, it accumulated visual material haphazardly, most of it donated by wealthy white men. Once the Library Company created a graphic arts department to scrutinize what it had, librarians and curators could see the inherent bias in the collection.

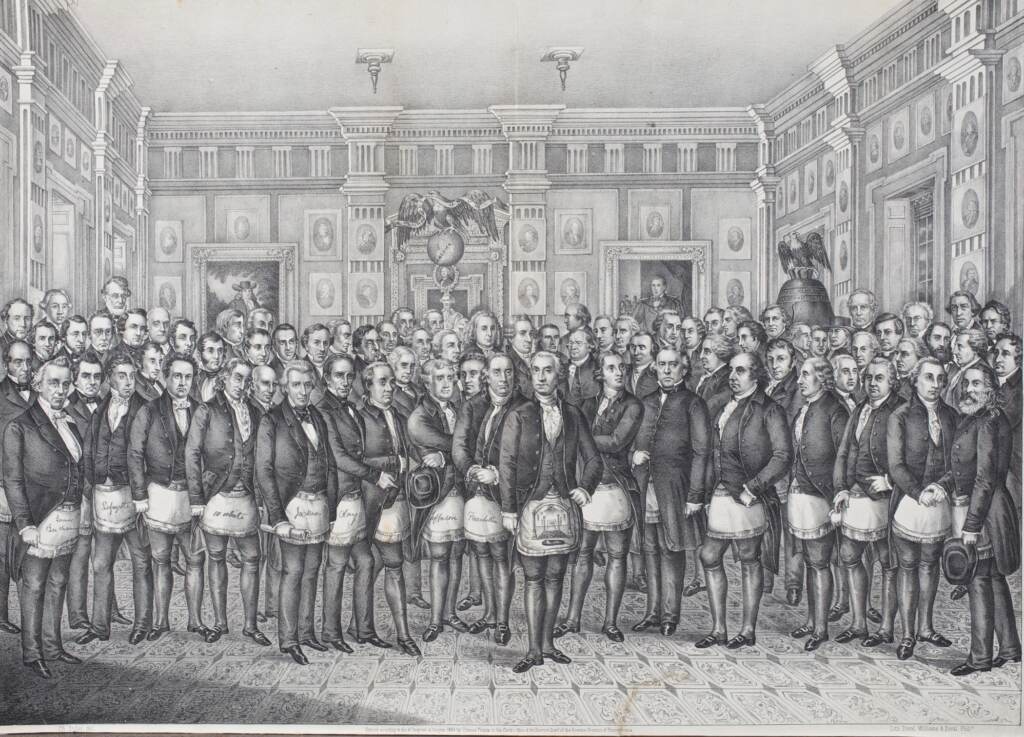

One of Piola’s favorite images in the exhibition is an etching of the members of a Masonic society circa 1860, featuring several dozen members of the society at the time, but also George Washington and Andrew Jackson.

“I just sort of fell in love with this print,” said Piola. “George Washington is not alive, but he’s being shown in Independence Hall, in the Assembly Room.”

The print was commissioned by Thomas Phenix, a fellow Mason, and was likely meant to honor the esteemed individuals in the society at the time. To today’s viewers, however, it reads as a sea of white faces.

All of them are wearing small white aprons, a ceremonial accoutrement of the Masons evoking their roots in bricklaying. To a more modern sensibility, the dignified older men appear to be wearing miniskirts.

“I find it funny. I don’t think it was meant by Thomas Phenix to be a funny print,” said Piola. “Yes, they’re wearing aprons and they are both living and dead people. Yes, it’s a sea of white men. I hate to love this, but I do. I do love this print.”

The graphic arts collection at the Library Company took a big turn in 1991 when the Stevens-Cogdell/Sanders-Venning Portrait Collection was donated by an African American family which can trace its roots to slaves on an 18th century plantation in South Carolina. The collection includes photos, scrapbooks, and visual material of Black Philadelphia from the mid-19th century. The Library is now known widely as an important repository of historic Black visual material.

“Imperfect Histories” outlines the essentials of visual literacy – who is attempting to communicate through an image, and who is it intended for – and how the sensibility has been applied over the last 50 years.

“When the graphic arts department was started in 1971, it was a period of social and political upheaval. Individuals were suspicious of our democratic institutions,” said Piloa. “When we started to think about this exhibition, Donald Trump had just been elected. It was a similar climate, being really suspicious of our democratic institutions and a rise in racism and misogyny. [Trump’s] quote that his inauguration was larger than Barack Obama’s, even though you would see these side by side pictures, I was, like, ‘No, Donald, your inauguration doesn’t look as large as Obama’s.”

Despite claims by Trump and his press secretary at the time Sean Spicer that his inaugural ceremony was the best-attended in U.S. history, the turnout in 2017 was about ⅓ of Obama’s in 2009, an estimation backed up by aerial photography.

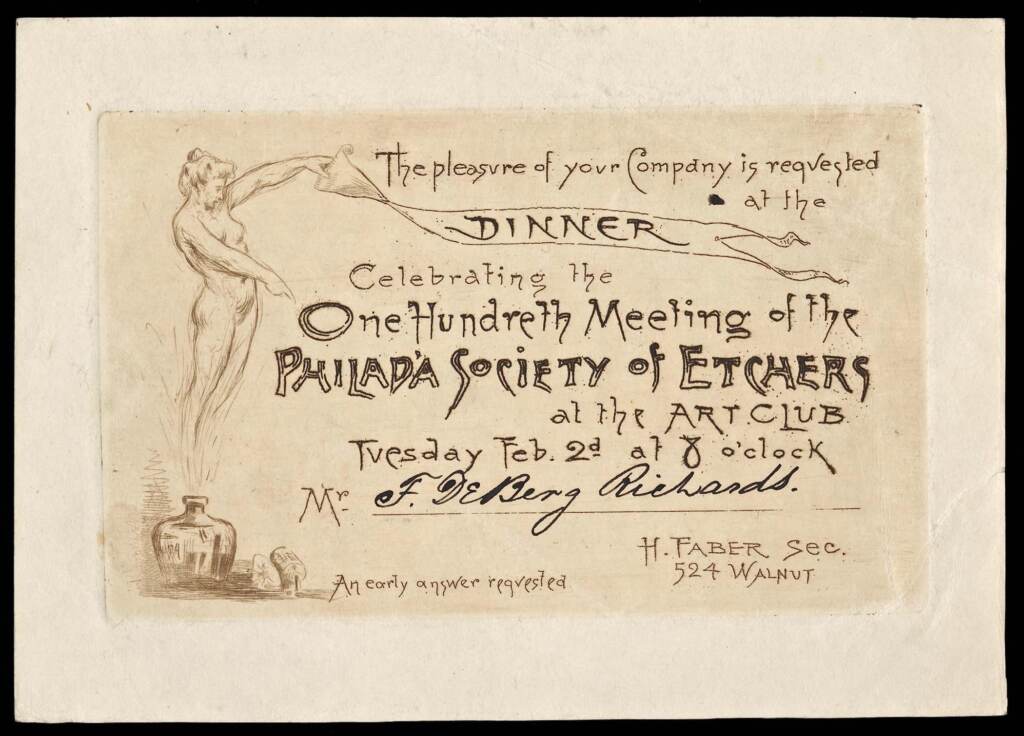

Some images in “Imperfect History” appear innocuous on the surface. There is a printed invitation to a dinner of the Philadelphia Society of Etchers, a professional association of illustrators. The card for the 1892 social event features a drawing of a nude woman who appears to be floating out of a bottle of ink.

What at first appears to simply be an announcement illustrated with an example of the society’s specialty, gets complicated when the viewer learns that the Society of Etchers was a male-only organization, explicitly barring women artists from joining.

“She’s not representing the Greek muse that is inspiring these artists. She is the naked woman that you might be thinking of that lives down the street, the attractive female ideal from the late 19th century,” said curator Sarah Weatherwax. “I just saw that invitation as representing clubbiness, the exclusion of women from a lot of opportunities.”

“Imperfect History” includes prompts in the wall text, guiding visitors to ponder why they think a particular image was made, and who was meant to look at it. The show makes transparent how the Library Company’s own visual literacy has changed over the years.

“I was thrilled that my close-looking skills improved after co-curating and thinking about all of these topics,” said Weatherwax, who has been at the Library Company for over 25 years. “I hope I didn’t write the same labels that I would have written two years ago. That really excited me to think that I haven’t grown too jaded with material that I’ve looked at for years and years and years. I still can find new ways of thinking about it.”

“Imperfect History” will be on view at the Library Company until April 8. A symposium about visual literacy is planned for March.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.