‘Ugly sounds we can play with’: Sound Museum Collective offers liberation through electromagnetism

An exhibition pulls electromagnetic signals out of the air and into the hands of visitors as a form of social liberation.

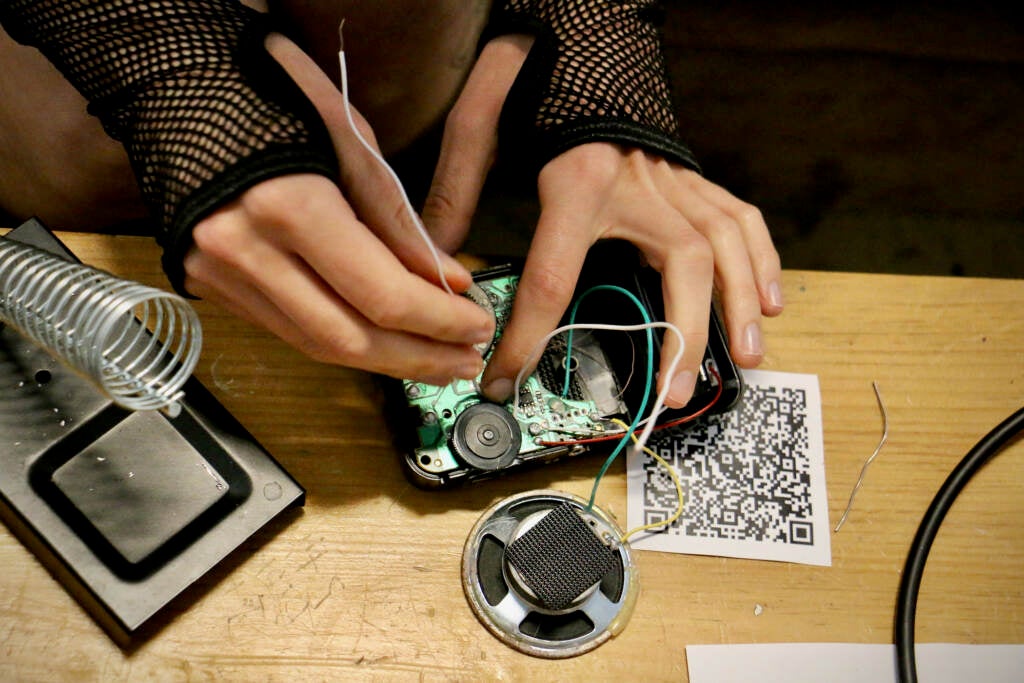

Elissa Anderson (left) and Jackie Milestone of the Sound Museum Collective work on the broadcast lounge that is part of thier exhibit at the Asian Arts Initiative. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Magic wands are now available in the 1223 Storefront Gallery of the Asian Arts Initiative, in Philadelphia’s Chinatown. They don’t make things disappear, but rather make invisible things appear.

The wands are wired to an amplifier and tipped with a copper coil making it receptive to electromagnetic waves, not unlike a pickup on a guitar. Wave the wand against a tower built of electrical transformers, it creates a drone. Wave it against a wall of television screens, and the drone changes.

If two people use two wands on two TVs, it could trigger a phase shift, turning the drone into a rhythmic pulse.

Visitors can pull electromagnetic waves out of the air, reveal them as audio signals, and manipulate them in real time. The exhibition, Body Conduit by the Sound Museum Collective, turns the world into a playground of sound.

“Personally, it kind of blew my mind when I found out that all waves are part of the same spectrum of waves. They’re just existing at different frequencies,” said audio engineer Elissa Anderson. “So a radio wave is the same, in essence, as color. Which is kind of nuts.”

Anderson is a member of the Sound Museum Collective, a group of audio engineers and electronic tinkerers who want to teach and inspire women and LGBTQ people to embrace sound technology.

“It’s been historically a cis boy’s club for a long time,” said Collective member Jackie Milestone. “In our professional experience, and in our experience, before we were professionals just learning about gear, we ran into a lot of unwelcoming spaces. I’ll speak for myself: I didn’t feel like I could ask a question.”

The Collective seeks to create safe spaces for historically marginalized people to learn about audio technology and circuitry, and facilitate new relationships with sound.

They are inspired by avant-garde composer Pauline Oliveros, a pioneer of experimental electronic music who championed “deep listening,” or becoming acutely aware of all the sounds around you.

“How can we really tune into our sonic environment?” said Milestone. “It’s a physical experience as well as an emotional experience. With our selective attention spans that exist for survival, we have to tune so much out. What happens when we’re being mindful of all the sounds around us?”

On one wall of the Asian Arts Institute is a diagram explaining what happens when radio waves go out into the world: they are deflected, scrambled, and diffused by myriad objects and interferences.

The world causes glitches. The Collective leans into them.

Opposite the diagram is a wall of battery-operated, portable transistor radios. Each is opened to its circuit board, which has been modified by two wires soldered into random connection points. These are bent circuits: the radios will play stations normally until you touch the wires together, which causes a short-circuit and collapses the radio signal into a shrill tone. Dialing the tuning knob modifies the electronic squeal.

The bent circuit radios were made recently during a workshop at Fleisher Art Memorial, where the Collective taught the basics of circuitry and soldering, and how anyone with simple tools can manipulate electronics to make them do things they were not designed to do.

“We found that doing stuff with the capacitors in particular was really interesting. But some of the resistors also were wacky,” said Anderson. “We just messed with that for a while until we found some really ugly sounds we could play with.”

One of the Sound Museum Collective’s current research projects investigates the history of radio and radio engineering as a technology for social liberation. As an analog form of information technology, radio waves are free of internet algorithms and digital tracking.

Called “The Emotion of Real Time,” the collective’s research project explores the historic and potential ways radio signals could help build queer community.

“So much of our communication is going towards the internet, but I feel more removed from that technology. I don’t have as much say if somebody, somewhere decides to take down a post of mine,” said Milestone.

“But when you’re talking about local radio stations, it’s literally an analog technology that’s happening in the air, in real time,” Milestone added. “It feels like a really valuable source of communication to be acquainted with and not forget about.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.