Reimagining vacant schools as vibrant community spaces

A vacant school is more than a silent, empty building. It’s a public promise waiting to be renewed. Since closing 27 schools in 2013, Philly is ripe with these promises. As the city works to sell off these closed schools, there is a mix of optimism and nerves. For some, the future looks promising in terms of reuse: South Philly’s Bok could be reborn as a creative hub. University of the Sciences plans to turn West Philly’s Alexander Wilson into student housing. Several others could become schools again.

But what about the schools no one wants? What becomes of schools where no one is expressing interest – even at a cut rate – in taking on a tough reuse project? Just because they may sit in a weaker market doesn’t mean these places aren’t full of potential, ripe for new life that anchors communities anew.

To help dream up new ideas for the challenging subset of closed schools the Community Design Collaborative hosted a reuse charrette with about 100 participants in November in partnership with the city, AIA Philadelphia, and staff from the design firm KieranTimberlake. The focus was two closed schools where there is no clear market-driven future: Old Frances Willard in Kensington and M. Hall Stanton in Lower North Philadelphia.

Beyond their educational functions, schools are also important community hubs, architectural landmarks, and vessels of shared history for generations of neighborhood residents. Neighbors and charrette participants were charged with considering how to capitalize on these attributes, how each site could be activated with new uses that help meet community needs and stimulate reinvestment – in the long and short terms.

Emily Dowdall, an author of the Pew Research Initiative’s recent study on the challenges of reusing schools, told charrette participants that the biggest obstacles to school reuse include scale, age, and location. She also noted that the negative community impact of an empty school building could pack a bigger punch than closing itself. But too little consideration is given to this secondary blow.

Schools left to languish can deteriorate quickly, making them less physically viable for reuse. Their vacancy can be a forlorn or foreboding presence for neighbors. Short-term projects at these sites could combat these risks, set the stage for more permanent investment, while rekindling community ties to school properties. Plus, interim uses can be a stabilizing and smart influence as redevelopment interests align, financing secured, purchase is finalized, design completed, and permits acquired.

After neighborhood meetings to collect community-driven preferences for new uses, four charrette teams brainstormed permanent and interim uses for each school property. The goal was not only to showcase each school’s redevelopment potential but also to offer concepts that could be explored at other, similarly challenged sites too.

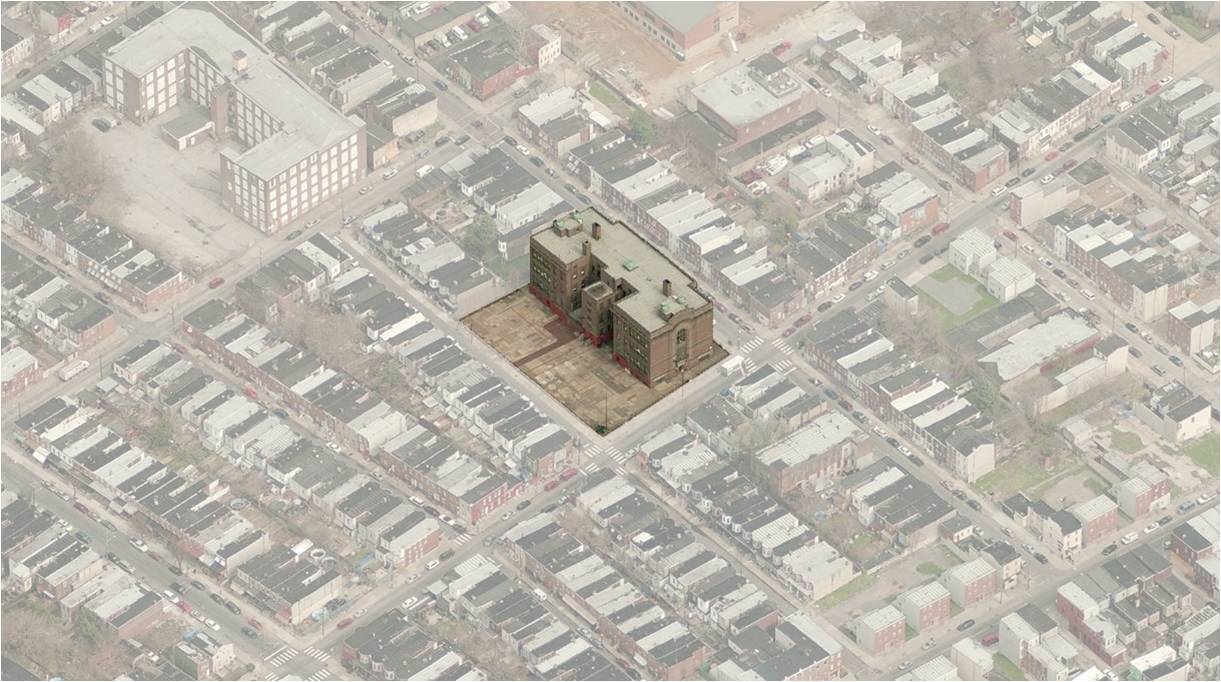

M. Hall Stanton is a large, L-shaped late 1950s school building near Broad and Lehigh with refined mod lines. It occupies a huge site, and its interior boasts generous spaces like an auditorium and gym in addition to a big schoolyard and adaptable classroom spaces.

Community members identified a residential reuse as their ultimate hope for Stanton, and pointed to an unmet demand for “intergenerational housing” that could serve grandparents raising grandkids. Other ideas included spaces to foster entrepreneurship, community gatherings, recreation, and new green spaces.

The Stanton charrette teams recognized the potential for transitional uses, including urban farming on the schoolyard, using first floor areas as “flex spaces” for classes or meetings, and even suggested a café in shipping containers outside. In the long run the team envisioned putting intergenerational housing on the school’s upper floors, a market farm and performance space outside, arts programming in the auditorium, and sports in the gym.

SEE M. HALL STANTON:

Kensington’s Old Willard was built in 1907 and is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Its classic stone construction, huge windows in every room, wide halls and original millwork give it an architectural pedigree and an edge from a sustainability perspective, but it is not handicap accessible and its masonry bearing walls limit adaptations. Neighbors of Old Willard said they would like to see affordable senior housing, youth and health related uses, and greening of the site to create a new, safe community space.

Willard’s charrette teams envisioned interim use as a new shared open space along with a “community flex-space” to help bring neighbors together by helping neighbors craft the space together through greening, art, and events. The long-term hope is affordable rental housing, with a schoolyard transformed to accommodate urban farming, play areas, and green stormwater management tools. To take advantage of the wide hallways, design solutions could help create “front porch” environments for residents to carry over social aspects of stoop life.

A full exploration of these community-connected concepts for Stanton and Willard are being compiled in a report by KieranTimberlake and the Community Design Collaborative.

See Old Frances WIllard:

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.