Philly Rail Park’s first public art festival highlights its locomotive history

The three-week “Site/Sound” festival spotlights parts of the old track bed that have not yet been developed into Philadelphia’s new Rail Park.

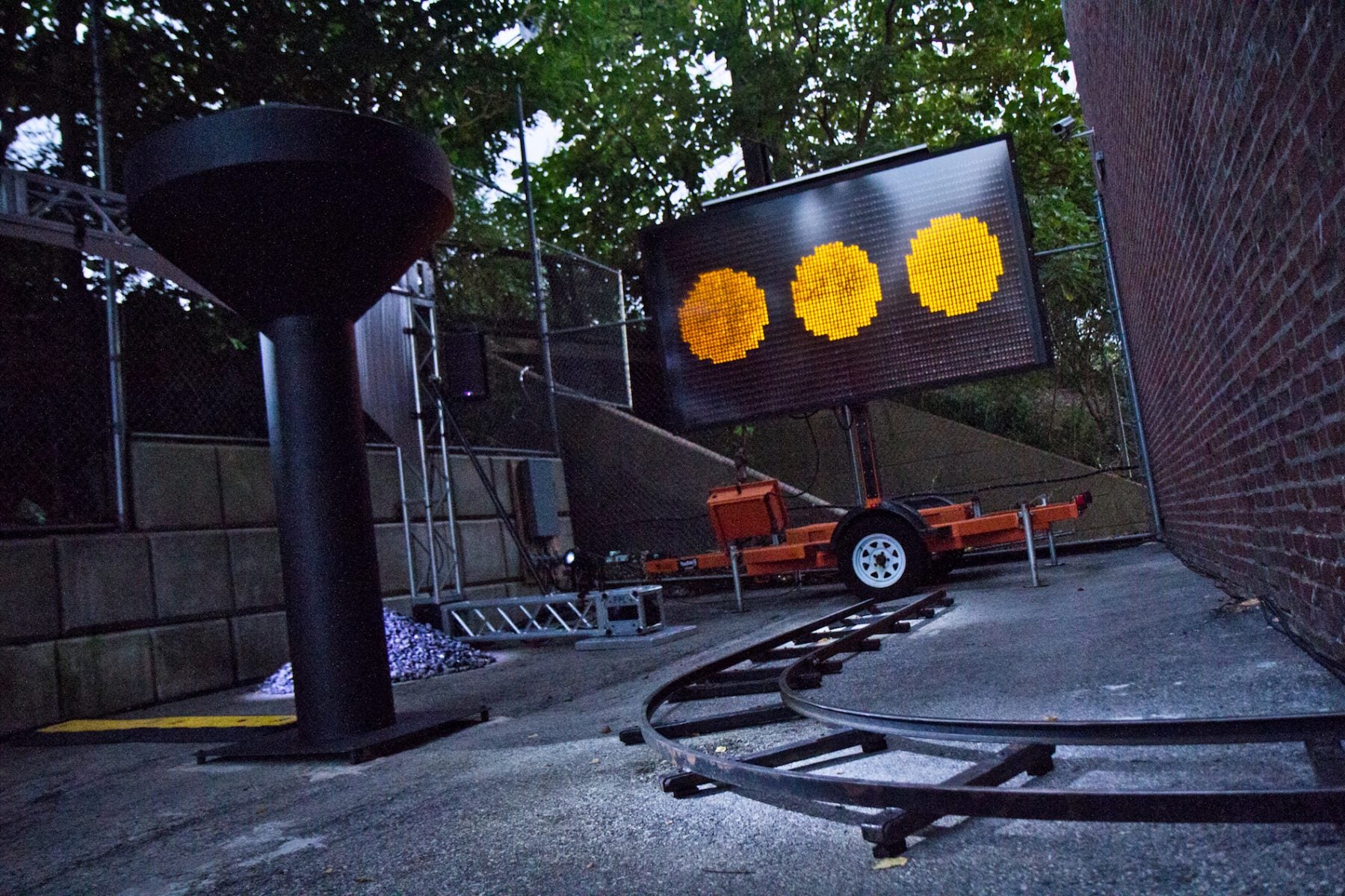

Aspect 281 at 990 Spring Garden Street is part of Site/Sound: Revealing the Rail Park, a public art festival. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

The largely abandoned parking lot near 10th and Spring Garden streets in Philadelphia, sandwiched between a four-story building and a railroad overpass, was not the first choice for installation art team Carolyn Healy and John Phillips.

What tipped the scales for them was a feature up above, on the rail bed. Steel trusses straddle the unused tracks, mounted with old railroad signaling equipment.

“We got interested in not this beautiful site — which is not beautiful, there was nothing here but an old couch — but what is it about railroads and signals?” said Phillips.

He and Healy, his longtime collaborative partner, laid down remnants of rail tracks in the parking lot, created replica locomotive smokestacks billowing steam, and installed video projections of abstracted train films. A 30-minute sound piece made of train sounds and electronics plays on a loop on mounted speakers.

“We were enthralled with the whole romance of steam trains,” said Healy, “as many people are.”

Their installation is part of “Site/Sound: Revealing the Rail Park,” the park’s first public art festival since it opened just over a year ago.

The current park stretches over a quarter-mile of unused, elevated railbed cutting across North Philadelphia.

But Friends of the Rail Park are not done. There are three miles of unused rail bed ripe for public space, riding above and below street grade. The Friends of the Rail Park are eyeing all of it.

The “Site/Sound” festival, created by Friends of the Rail Park and Mural Arts Philadelphia, begins Saturday and runs until Oct. 19. It spotlights parts of the old trackbed that are not yet developed into the public park.

“We want to engage diverse audiences, engage the community in a different way,” said Kevin Dow, director of Friends of the Rail Park. “We believe that providing a high-quality artistic experience in public space will bring everybody to us.”

The three-week festival features three commissioned installations. The artistic team of Erik Ruin and Rosie Langabeer used a primitive cinematic device called a zoopraxiscope, a hand-cranked contraption that animates images.

The zoopraxiscope has a tentative historical relationship to railroads, as it was a device favored by Eadweard Muybridge, an early pioneer of moving pictures. The president of the Central Pacific Railroad, Leland Stanford (an industrialist and later California governor), used part of his vast fortune to support Muybridge’s early experiments in motion-picture technology.

In their “Soon, Now, Gone” installation, Ruin and Langabeer used the zoopraxiscope to relate cinema and rail, two things that alter time — in a way.

“The railroad at the time of its founding was a technology that transformed people’s subjective experience of time,” said Ruin.

Film manipulates real-time into cinema time; railroads forced the world to adopt artificially delineated time zones.

The other major installation, “Moon Viewing Platform,” is in the railroad cut at 18th and Callowhill streets, a below-grade rail bed. Standing on the street, viewers peer down into a gulch that artists Nadia Hironaka, Eugene Lew and Matthew Suib have transformed into an illuminated landscape of wild plants and gravel paths.

Typically, the cut is filled with trash and weeds.

“It’s a borrowed landscape, there for just three weeks,” said Lew. “It’s also a collaboration with the environment. The vegetation will eventually take over the space.”

The space is in the shadow of a large building with a vast, mostly windowless wall. The artists created a film evoking gardening, projecting it in a huge display against the building.

The installations are just the start. They will be accompanied by live music performances throughout the festival. Every weekend during its three-week run, musicians and sound artists are scheduled to perform inside each installation.

“The impact will be fullest when you attend the performances on Saturday evenings,” said curator Gene Coleman.

Bringing music performance, sound art, and visual installations together in public spaces is rarely done, Coleman said.

“If we have public art and it includes this new media, these new forms of expression, public art completely changes in terms of what it can do, what it can communicate,” he said.

Editors note: This story has been updated to reflect that artist Matthew Suib was also involved in creating the “Moon Viewing Platform” piece.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.