What does it mean to create a new park in a changing, sometimes contested neighborhood? Next in our series about Philly’s changing public spaces, Ashley Hahn takes a deep dive into the Rail Park’s growing pains and lessons learned. The Rail Park’s first section will open June 14.

—

In a one-block span in Callowhill, you can find high-end condos in a rehabbed industrial building, an EDM nightclub with bottle service, a 25-year-old social-practice arts organization, and a 250-bed men’s shelter. It’s a neighborhood where tofu, awnings, restaurant kitchen equipment, paintings, software, and craft beer are made. Sometimes on the same block. Which is to say Callowhill – the neighborhood nestled between Spring Garden and Vine streets, Broad and Eighth streets – is complex, layered, and shape-shifting.

Cutting through it all is the former Reading Railroad’s disused rail viaduct. Its drippy stone tunnels frame views across the neighborhood like dank portals. Its surface sprouts weed trees and reedy grasses where trains once ran. Just as Callowhill’s industrial buildings are being reused, part of the historic viaduct is being repurposed into the neighborhood’s only park.

The Rail Park’s first quarter-mile section, which officially opens on June 14, follows the gentle curve of a former rail spur, rising from Noble Street just east of Broad to the middle of the 1100 block of Callowhill Street. Ultimately, the Rail Park is envisioned as a three-mile linear park that might someday connect 10 neighborhoods, from Poplar to Brewerytown. The first phase has cost about $11 million, and reuse of the rest of the elevated viaduct as a park easily could exceed $50 million.

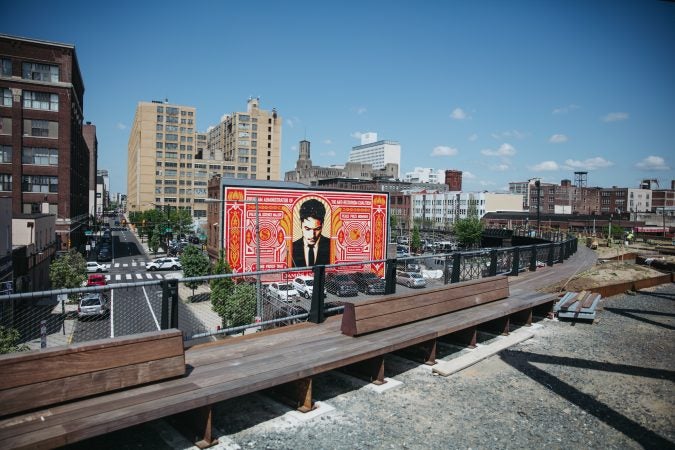

From on high, the Rail Park offers sweeping views with a rare perspective on a neighborhood in transition and the city beyond. Meanwhile, the rest of the viaduct remains a feral landscape that is, depending on your outlook, a romantic ruin providing a connection to history or a blight better torn down.

The stone structure supporting the new park has been spruced up and stabilized. Yet walking next to the rest of the viaduct means passing mounds of trash, waist-high weeds, homeless encampments in cave-like underpasses, and wedge-shaped lots used for surface parking. The park feels a world away, but squint and you can imagine it someday transecting the neighborhood. What you picture likely depends on your perspective on Callowhill’s change.

If public spaces are like a mirror, the Rail Park reflects a neighborhood with many faces. So many aspirations and fears around change in Callowhill are seen in the Rail Park, fairly or not. To some, it’s a clear sign that Callowhill is on the development map. To others, it’s a long-awaited public amenity in a neighborhood with none. Its potential as a public space, where neighbors connect, quickly runs up against concerns about “green gentrification,” where park investments can result in higher property values, or cause physical or psychological displacement.

“We want this to be a park for all, but we are very, very aware that parks like this can separate communities more than bring them together,” said Friends of the Rail Park board member Tiffany Newmuis.

Questions about who the Rail Park is “for” are wrapped up in neighborhood dynamics, touching on the complexities of identity and inclusion, who is driving change and who can keep up.

For boosters like Paul Levy, president and CEO of the Center City District instrumental in realizing this first phase, the Rail Park is part of a growth strategy for an already-diverse neighborhood just north of Center City’s core. “Amenities are key to attracting residents and workers. This is clearly part of that strategy, but we need to think beyond just how do you stimulate real estate to ensure that you have a mixed-income, mixed-use neighborhood.”

But the nature of that growth matters to groups like Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation, which has fought for more than 50 years to defend Chinatown’s right to self-determination as a neighborhood. It lost its fights against the Vine Street Expressway and the Pennsylvania Convention Center, which hardened the neighborhood’s northern and western edges, but it successfully batted away proposals for a stadium and later a casino.

Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation (PCDC) sees Chinatown North, most visible in Callowhill’s eastern half, as the neighborhood’s best hope for economic and housing opportunities. It is staking a new claim there with the construction of a 20-story building, its crane like a flag planted on the north side of 10th and Vine streets. The project, called Eastern Tower, includes commercial spaces and apartments, but also a much-needed gymnasium and community center. A 2017 neighborhood plan emphasizes public space and connections to Chinatown North.

“I think there’s no question that public space is hugely needed in Chinatown,” Sarah Yeung, PCDC’s former director of planning, said. But that’s not to say that the construction of the Rail Park is the right fit. “This is taking place in a land market where the environment around real estate and wealth is changing the neighborhood.”

Developers like Craig Grossman of Arts & Crafts Holdings tend to call Callowhill – or, as his company prefers to call the pocket it largely owns, “Spring Arts” – the “hole in the doughnut,” bypassed by Greater Center City’s growth but an attractive location. Arts & Crafts recently acquired eight buildings directly adjacent to the old viaduct. “You can’t replace what’s here,” said Grossman, best known for his role with Goldman Properties in reinventing once-gritty 13th Street as “Midtown Village.”

In the viaduct’s decrepitude, Grossman sees authenticity and an industrial-chic design element. The park is the kind of lifestyle amenity he says will only add to what the company is already doing in the neighborhood, reusing old industrial buildings for creative business and adding commissioned street art outside. “We saw that we could control these properties in critical mass. With a lot of our relationships and our attraction to the creative class – arts, culture, tech, small business – we thought that this was an opportunity to make a center for that class and we could build and curate a community around these like-minded kindred spirits.”

At the other end of the spectrum is Rosalyn Forbes, director of development at Sunday Breakfast Rescue Mission, a 140-year-old neighborhood institution supporting individuals experiencing hunger and homelessness. She sees in Friends of the Rail Park earnest community partners and welcomes the park as an amenity for the individuals Sunday Breakfast serves.

Welcoming public spaces, Forbes said, “could really impact the morale of the men, women and children that we serve and possibly ignite in them a desire to join a program, get their life back on track, change their perspective.”

“I really do think a lot of it will come down to the perspective of the privileged people who are coming to use [the park] and how welcoming they are.” Everyone deserves to enjoy this new space, she said.

For others, the project brings the neighborhood’s contrasts and potential into high relief. “I think there are a lot of people who just think of the elevated level of the Rail Park and how amazing that’s going to be. And I’m right there with them… But people who walk through the neighborhood under the [viaduct] have a different view,” said Julia Millan Shaw, deputy director of Asian Arts Initiative, which just celebrated 25 years of social-practice art in the neighborhood. “What’s going to happen to the viaduct tunnels that are beautiful, and have the potential for programming and arts, but lately have really become like a home for people?”

Could the park create an upstairs/downstairs version of the neighborhood?

Ellen Somekawa was president of Asian Americans United for 18 years before becoming principal of a charter school in Callowhill in 2014. Over time, she’s heard plenty of concerns about the park contributing to neighborhood change. “At the same time, the message cannot be that if you’re in a poor neighborhood that you can’t have green space, and if you get green space, you lose your neighborhood. There has to be another way.”

In April, Kevin Dow became executive director of Friends of the Rail Park, the latest incarnation of the 15-year-old volunteer advocacy effort to turn the rail right of way into public space. Dow is a Philly native whose career path has included community-affairs work for Wachovia, time as the Commerce Department’s chief operating officer, and running United Way’s impact agenda for the region. Over time, he said, he hopes the Rail Park can grow into a public space that “represents us” as Philadelphians. The most exciting challenge, for him, is how to make this park an engine of inclusion and equitable development. “If we do that successfully, this could be a model park in the nation.”

The Rail Park is freighted with the weight of these expectations, and it’s not even open yet.

No pressure.

Park dreams

It was high noon on a sweltering spring day, and Center City District president Paul Levy and I were walking the Rail Park, careful to avoid the many workers building benches and setting stone pavers. At that hour, there was little shade. His shirt sleeves were rolled up, and I was getting a sunburn.

We slowly traced the new park from its street-level entrance at Noble Street, where it opens to a set of tiered wood platforms, a gathering spot set against the backdrop of a metal map interpreting the neighborhood’s industrial history. The map, designed by the firm Cloud Gehshan, will help orient visitors but also muffle the whirring of the huge industrial fans that cool the server farm next door.

We crossed the former rail bridge above 13th Street, reused and reinforced, which will have a planter garden along its south edge that offers a glimpse of the park from the street below. From here, the park rises gradually, taking a wide curve through clusters of trees, raised gardens, and chunky wood benches. It culminates at heavy-set wood-and-steel swings suspended from a zigzagging industrial frame. Steel gates stand just beyond the swings marking the park’s terminus, for now, at one of the two staircases that currently connect the park to the street.

The idea for this first phase, Levy said, was to “give the neighborhood a backyard” by reusing a piece of its industrial history.

We ran into Bryan Hanes, whose Callowhill-based landscape firm designed the park, as he checked in with a contractor. Hanes explained that the design uses elements of domestic landscapes like planter boxes and porch swings at a civic scale. But its materials play on the color and textures of the old rail line: corten steel that will rust to a color like the old catenaries; and ipe, a tropical hardwood, in chunky dimensions reminiscent of rail ties.

We looked to the wide viaduct beyond the gates, at what could become a future phase of the park. It is still owned by Reading International, a company that primarily owns entertainment properties. We could see where the park spur merges with the old railroad’s main branch in a broad meadow that dead-ends above Vine Street. Looking to the north and east, we could see the viaduct growing wild as it runs into East Poplar.

For now, the very form of the Rail Park’s first phase, following that old rail spur, could influence how it is used. As Ellen Somekawa noted when we spoke, the first phase “is going to orient to the higher-income section of the community, toward Broad, and is not going to be perceived as very accessible to the Chinatown side.” It’s the future phases she feels more excited about – particularly the wide, plaza-scale area where the viaduct abruptly ends at Vine Street. “It offers so much potential to serve the Chinatown community.”

Future phases of the park could also connect different neighborhoods. But for now, this is it. And to Levy, it’s important that this park can stand alone – at least for a bit.

“It’s not that I am skeptical about the broader vision, but this park has to work in its own terms. It is obviously the only green space in this neighborhood, a neighborhood that’s clearly growing fast with both workers and residents,” Levy said as we turned to walk back down through the park.

According to a 2017 emerging-market report, the number of building permits in 2016 doubled from the prior year in Callowhill because of “rapidly increasing development pressure from the neighborhood’s periphery and the promise of the first construction phase of the Rail Park.” The report by FixList and Jones Lang LaSalle also found that property sales nearly tripled between 2010 and 2015, and that the neighborhood’s median income went up 15 percent. Updated zoning now enables denser residential development in Callowhill.

So what does it mean to build a park for a neighborhood that’s changing? What about the park’s own role in driving that change?

Levy wants us to shelve analogies between the Rail Park stoking interest in Callowhill and the ways Manhattan’s High Line accelerated development in Chelsea into hyperdrive. “I think that’s a substantive issue, but we need to separate lower Manhattan and superheated growth from slow-growth Philadelphia,” he said, pointing to the blocks of surface parking we were overlooking from the park. “Thirty-three percent of the land that surrounds this park is vacant or parking lots… So, there’s a lot of room for development that could be market rate or affordable or a mixture of both.”

It’s thinking about that opportunity, Levy and others argue, that requires a comprehensive strategy – an idea still very much in embryonic form – to recapture a portion of the revenue from future developments here in ways that could support both housing and public-space goals. What tool might be best used is far from set. But is he interested?

“Absolutely. I mean, that’s the only way to do the second phase.”

Growing pains

Levy is a Rail Park evangelist who says he’s “obsessed” with seeing the whole park built. He is also quick to share credit with the early believers – especially the advocates who have spent the last 15 years articulating visions for a park-like public landscape on the viaduct.

Levy’s conversion to the gospel of Rail Park came via a 2009 walk with Sarah McEneaney and John Struble, who founded the Reading Viaduct Project in 2003. In the early years, when McEneaney and Struble were pitching the park concept to anyone who would listen, they took Levy on a tour. It just so happened that the week prior, Levy had visited Manhattan’s High Line for the first time. Up on the viaduct in Callowhill, Levy said, he immediately saw its potential, and by the time they were leaving he was brainstorming.

Around the same time, Liz Maille and the late Paul VanMeter were also inspired by exploring the full three-mile former rail right of way, and founded VIADUCTgreene. Friends of the Rail Park was established in 2013 when the two groups merged. Maille now serves as its board president, and McEneaney and Struble are still involved as board members.

This spring, I joined McEneaney and her dog Mango for a walk to talk about the neighborhood. McEneaney is an artist who has lived in Callowhill for 39 years, and serves as president of its neighborhood association. We took off from her gate, weaving our way around the viaduct at ground level, checking in on the park from Noble Street. While she delights in the park’s progress, McEneaney also spoke frankly as we walked about the advocacy effort’s growing pains – particularly the criticism that the park did not have an inclusive enough community-oriented design process.

“When this was an idea, it was my impression that engagement was something like, ‘Hey guys, there’s this idea. Who’s interested?’,” McEneaney said. That may have been what the park advocates were capable of doing at the time, but it was hardly sufficient. The group was, after all, an all-volunteer organization until hiring Dow in April, maturing even as the park it organized around was being built.

“We admit that we haven’t been perfect. And that’s why we’re so excited about hiring our executive director, and why so much of the discussion is around community and outreach. And [why] the second hire is going to be in community engagement,” McEneaney said as we walked up 11th Street past the Trestle Inn, looking up at a section of the viaduct where weedy paulownia trees bloom purple, like some lost hanging garden. “For further phases of it, we definitely know we have to do better engagement for the design. We know that, we accept it, we’re eager to do it.”

Skilled as Center City District is at cultivating political support and managing park construction, civic engagement has never been its strong suit. As Levy once put it, “I’m in the business of getting things done.”

But that has meant neither of the project’s major boosters prioritized the robust kind of engagement required – if the goal is a shared vision for a public-space project in such a fragmented neighborhood. Compounding the challenge is some enduring confusion about who actually speaks for the Rail Park. As the park opens, that could remain murky as Center City District, Friends of the Rail Park, and Philadelphia Parks & Recreation partner in its programming, fund-raising, and management.

McEneaney acknowledged that there were people invited to participate in early conversations about the Rail Park’s design who either did not respond or chose not to participate. That, she said, even extended at times to key neighborhood stakeholders like Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation.

PCDC’s executive director, John Chin, recalled wanting to see plans for the park dovetail with affordable-housing development in the neighborhood. Center City District even engaged architect Cecil Baker to study the potential for affordable housing in Callowhill. But as conversations with park advocates and neighborhood leaders got deeper, Chin said, there was a split in the road: Park advocates said they didn’t know how do to affordable housing and, rather than find ways to learn or partner, suggested that PCDC tackle housing while they focused on the park.

And during the same period when park partners and designers were asking for community input about conceptual designs, the project was also wrapped up in a pitched battle over a proposed Neighborhood Improvement District in Callowhill. The NID, introduced in 2011 and backed by Center City District, would have provided dedicated funding for public improvements – initially including the viaduct park – through an additional 7 percent property tax. Residents and businesses balked. PCDC called out the proposal for its lack of transparency and questioned who would control and benefit from the NID. The proposal tanked, failing to find enough property-owner support to pass. Say its name and people still sigh heavily.

Now, just as the Rail Park is set to open, a similar proposal has surfaced to establish a Callowhill Business Improvement District. As PlanPhilly reported last week, if approved the BID would similarly use an additional property assessment to deliver neighborhood services or public-realm projects. BID boosters, like Arts & Crafts Holdings, see it as a way to clean up trash or add lighting. Others I spoke with have reservations, echoing concerns that came up during the NID debacle years ago, mostly over whose interests would be reflected on its board, which at this point is light on Chinatown North voices.

It remains to be seen if the neighborhood has evolved enough to support a special services district or if old battle lines will be redrawn. The rift over the NID ran as deep as the Vine Street Expressway, and led to a frosty stalemate between PCDC and the Rail Park project. Still, people who landed on different sides of that debate have found ways to work together.

Breaking bread, breaking ice

On a cold day last November, I tucked into the front table at Ray’s Café and Tea House in Chinatown, sitting in the cozy glow of its pink neon sign in the fogged window with Rail Park board member Melissa Kim and PCDC’s then-planning director Sarah Yeung. Kim is a program officer at LISC, a nonprofit focused on community economic development, and previously has worked in Chinatown North with Asian Arts Initiative. Their work as planners has overlapped in Chinatown over the years. Sitting across the table from one another, talking over coffee, there’s an ease between Kim and Yeung and it’s clear that they share a level of trust that’s rare in contested neighborhoods.

“I think the relationship between the Rail Park project, PCDC, and the community at large has been one that’s had a lot of tensions, and at times we’ve been directly in opposition. Right now, I think that there is still a standstill, in terms of where the PCDC board sees the project impacting the community,” Yeung said. But the impact of the Rail Park is already being felt “with the increasing trend of residential development north of Vine.” Yeung said PCDC is particularly concerned about the Rail Park’s effect on Chinatown North’s economy and affordable-housing supply because of “property-value increases that are going to be caused by the park and the impacts of displacement in a neighborhood that’s changing.” A secondary but important concern is that the park “include the local neighborhood, and really be for the local neighborhood, the people that live and work there.”

Chinatown has virtually no public space and its nearest park, Franklin Square, requires crossing the speedway that is Race Street. Getting to the Rail Park will require crossing the Vine Street Expressway.

“Those priorities were not the project’s priorities. But they are more open to talking about these matters now,” Yeung said as Kim nodded.

Something that has helped open the conversation, Kim said, is that a source of Rail Park funding encouraged project partners to think more expansively about inclusion. The Rail Park is one of the initial cohort of five Reimagining the Civic Commons sites, a now-national project that started in Philly in 2015, jointly funded by the William Penn Foundation and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. [Disclosure: Both foundations provide grant support to WHYY. This series is supported by a grant from the Knight Foundation.]

Kim said the Civic Commons Initiative got Friends of the Rail Park thinking beyond the physical aspects of the project to explore ideas about community identity, particularly through work facilitated by PennPraxis to convene partners and develop new programs. That led to more conversations with groups in Chinatown and Chinatown North.

Yeung led a tour of the neighborhood for the Civic Commons cohort, which Kim said likely would not have happened without the structure of that initiative. It helped break the ice a bit between Chinatown and the Rail Park – and created a chance for Yeung and Kim to collaborate.

“Sarah and I had been talking about what the Rail Park should mean for the neighborhood, but up until then it was just talk,” Kim said. “The board was an all-volunteer board. To do real community engagement takes staff… people think it’s going to be easy, but it’s really, really hard and takes a lot of planning and thought that we just weren’t doing.”

At the end of 2017, the two organized three community dinners, supported by a Civic Commons micro-grant. They invited a variety of people with different relationships to the neighborhood – including seniors living at On Lok House, residents of Francis House of Peace, young community advocates, Rail Park board members, and representatives from community institutions – to share a family-style meal and meet neighbors they might not otherwise know. They chose people who they thought would come with opinions, but wouldn’t just bring an agenda.

“We got to know one another around the table and talk about what we all desire around our community. We got to hear each other over a shared experience of food and create a positive memory,” said Rail Park board member Tiffany Newmuis. “What I loved was, walking away, it’s hard to ignore people who now you’re in relationship with because you shared a meal.”

PCDC’s involvement, Kim said, gave the conversations weight and meaning. And that’s not something Yeung took lightly.

“I don’t want PCDC’s participation to be misconstrued as in any way sweeping under the rug past mistakes,” Yeung said. “I think the NID was a disaster. It was incredibly acrimonious in the community, and I think that the impact of this huge project has deserved much greater attention than a few months before groundbreaking…. It’s late in the game to be talking about this, but from where I stand, we want to move forward to have positive impact on the community in some way, and this is the way forward because I think there’s trust between just me and Melissa, that we can start this conversation.”

Fast forward several months and things have changed again. Yeung left her post at PCDC for a new job at The Food Trust, though she says she hopes to stay involved in the project as a voice for Chinatown. Melissa Kim stepped back from outreach work during Friends of the Rail Park’s executive-director hiring process, but is back on the board’s community-engagement committee.

As to how Chinatown could be involved in shaping the Rail Park’s future, PCDC is circumspect. Any future process would have to be responsive to Chinatown’s needs and its input must be taken seriously.

“Engagement is only meaningful if there is a real opportunity for change on both sides, right? Otherwise, you’re just presenting something and checking off a box,” Yeung said.

For his part, Dow, Friends of the Rail Park’s new director, said he is willing to invest the time to bring more communities into conversations about what the park should be – as it exists today and in any future phases.

“Community development can’t be transactional,” Dow told me. “This is a project that will take 10 to 20 years. How do we, over that time, build credibility and confidence within different communities, Chinatown in particular, so we can have a successful project?” He said he intends to begin with a “listening tour to engage diverse communities, so they can be owners of the park and help determine what it feels like, looks like.”

Street views

Time was, McEneaney might have the viaduct all to herself. But the neighborhood is busier now, with more residents and businesses, and the new park is bound to bring even more people. On our walk, I asked McEneaney whether she missed those quieter days.

“I’m not the least bit nostalgic,” she said. “I lived here when it was scary and dangerous at night. It’s not like that anymore because there are people around.”

The luster of new investments, like the park or rehabbed buildings, brings the rest of the neighborhood’s condition into clearer focus.

As we walked through the viaduct’s moody underpasses, we talked about one thing everyone in the neighborhood seems to agree on: the need to improve street-level conditions, like lighting.

She didn’t blink as we passed a stray car bumper blocking what remains of a crumbling sidewalk at Ridge and Noble under the viaduct. Around another corner, we saw children playing in Folk Arts-Cultural Treasures (FACTS) Charter School’s only outdoor space, an asphalt yard.

The school overlooks the still-abandoned section of the viaduct, along what could be a future phase of the park. FACTS’ principal, Somekawa, told me she imagines her students will use the park, but thinks that will mean overcoming several physical barriers.

She hopes to see more attention paid to neglected streets and sidewalks around the viaduct. “Who knows what’s dripping from the water. It’s unpleasant, dark, unlit, unkempt. It creates a lot of bad pedestrian-level conditions,” Somekawa said. “My hope for future phases of the project would be that at least as much attention is paid to ground-level amenities that serve the people that live and work in the neighborhood as what goes on above it.”

That’s a frequent refrain heard in the neighborhood, and one that surfaced in Asian Arts Initiative’s recent cultural-planning process, called People:Power:Place. One of its outcomes was identifying shared spaces – both indoor and outdoor, like the park – to support community gatherings and cultural expression. But it was just as much about forging new partnerships among diverse community stakeholders, from Sunday Breakfast Rescue Mission to Arts & Crafts Holdings, around what it means to share Callowhill. And that could have lasting consequences as the neighborhood continues to work together to address how it evolves.

Most businesses I tried speaking with in Chinatown North about the neighborhood’s changing face didn’t want to talk. My speaking English was one barrier, but most people had work to do, customers to serve, deliveries to make. Some said they didn’t feel comfortable, while others simply were not interested. Among the exceptions was Ken Liang of Ken’s Automotive, the garage he’s run at 10th Street and Ridge Avenue for nine years.

“We get more business now because the population is increasing,” Liang said while working on a van. “But I know eventually we will get kicked out.” He doesn’t own the garage, and Liang thinks that the owner is unlikely to renew his lease when it’s up in a couple of years. “They’re going to develop it. I know it. Unless they sell it to us and let us develop it.”

He’d cash out too.

Liang lives with his young family in the Northeast but says he grew up in Chinatown. He’s well aware of the Rail Park project, and we could see it from his corner. But he said he’s not ”the kind of person to use the park,” calling it a luxury.

“I expect the more there’s residential here, they’ll probably start complaining about us,” he said, gesturing to new residential buildings next door and the recently cleared lot across Ridge, less than two blocks from a park entrance. The neighborhood is “in the phase where everything is changing and we’re in the middle of it. At one point, we’ll have to deal with the end result. I’ve been here my whole life. I’ve seen the change coming.”

To the extent that the Rail Park is shaping the way the neighborhood changes, there is also real interest in leveraging that energy to reinvest there. The fear is that those conversations may be coming too late for Callowhill.

Leaders like Paul Levy and Kevin Dow are beginning conversations about equitable-development strategies related to the park. The Rail Park is part of the High Line Network, which partly aims to help similar projects learn from the High Line’s example in Manhattan and think more deliberately about equity.

In some ways, discussions about using policy tools, such as a transfer of development rights program or tax-increment financing structure, around the Rail Park might be premature. The city does not control the rest of the former rail right of way at this point. But by the time it does, it could be too late to harness the development happening in Callowhill. Investors aren’t going to wait around for the city to get its act together.

Still, John Chin is hopeful. “The reality is that real estate prices only continue to rise. Was there a better time? Yes. But it’s not too late.”

To Yeung, it boils down to hard questions.

“It’s really about the land market that the Rail Park is driving, and it’s about preserving the neighborhood as a place of opportunity,” she said. “That’s something that we really need to think bigger about. It can’t just be about engagement and about planning for future impact, given where we are now with the timing of the project. I think we’re at a crucial juncture where we either need to step up and provide concrete funds and mechanisms to enable equitable development or not. And I think it’s a question of priorities. What’s more important?”

That the Rail Park provokes this kind of existential neighborhood question is testament to its power. A park like this is so much more than a park. In a physical sense, it will be the neighborhood’s first truly public space, where strangers can become neighbors. It now challenges neighbors to find new ways to make room for one another, to continue redefining what Callowhill is, how it should change, and for whom.

And as the Rail Park grows, its best hope is that these opportunities are met in each neighborhood it touches.

—

In Common is made possible through support from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.