Mayor Parker exploring 100% tax abatement for Philly properties in underinvested communities

The proposal may violate state law. It comes as the administration seeks to expand the city’s housing supply amid an ongoing crisis.

Listen 1:07

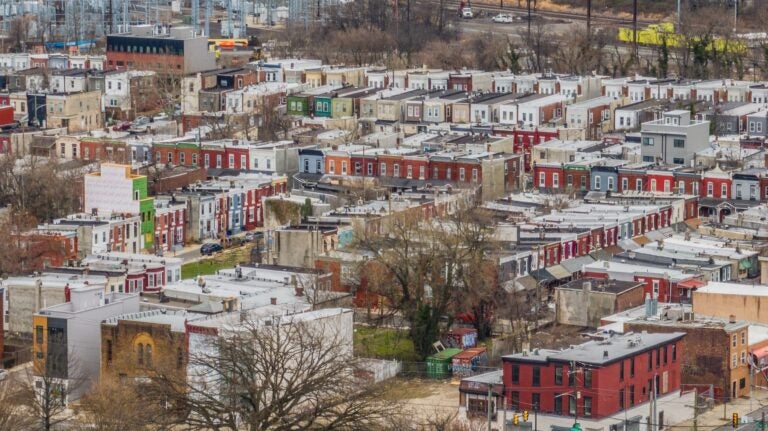

Housing near Fairmount Park in Philadelphia (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Have a question about Philly’s neighborhoods or the systems that shape them? PlanPhilly reporters want to hear from you! Ask us a question or send us a story idea you think we should cover.

Mayor Cherelle Parker’s administration is exploring the possibility of bringing back the city’s original tax abatement program to help spur real estate development in parts of Philadelphia that haven’t been “fully invested in.”

“It’s gonna have to be a discussion, but the idea would be that we do bring it back to 100% in certain parts of the city and not all of the city,” said John Mondlak, deputy director for development services for the city’s Department of Planning and Development.

The news came during a daylong budget hearing dedicated to Parker’s $2 billion housing plan, a multifaceted initiative designed to create or preserve 30,000 housing units over four years.

Mondlak told lawmakers the administration is set to meet with the city’s Law Department next week to discuss the legality of such a program, which he said may run afoul of the state’s uniformity clause. The clause essentially bars municipalities from taxing real estate at different rates.

“We’ve had initial conversations where the Law Department has kind of indicated that if you can establish definitively how you came to this rational reason for coming up with this strategy, that it should work,” Mondlak said.

Starting in 2000, residential property owners could obtain a 100% abatement for 10 years, enabling them to pay no property taxes during that time. The tax break also applied to certain renovation projects.

The goal of the program was to incentivize new development in Philadelphia. And proponents of the program, including many real estate developers, argue it did just that, benefitting the city and neighborhoods that suffered from a lack of investment.

Opponents later sought to dismantle the program, which they said continued to aid property owners in neighborhoods that no longer needed help from the public sector to grow.

The program’s current iteration, launched in 2022 after considerable debate, offers property owners a 100% abatement for the first year. The value then diminishes by 10% each year for the remaining nine years of the program.

Mondlak said Wednesday that the fate of the abatement proposal is essentially in the hands of the Law Department.

“If they look at it and say it doesn’t [work], then so be it,” he said.

Who will benefit?

For now, it’s unclear what role, if any, a new abatement program would play in the Parker administration’s housing plan, called the Housing Opportunities Made Easy or H.O.M.E. initiative. Until Wednesday, the idea had not been discussed publicly, and it’s not referenced in any available literature on the proposal.

And yet, bringing back the abatement would generally align with the goals of the initiative, which must be approved by City Council.

Parker has said she wants to make it easier for real estate developers to build new housing, incentivize housing revitalization projects, prevent housing instability and improve access to mortgage loans, among other priorities.

The H.O.M.E. initiative relies on the city borrowing $800 million in bonds, an unprecedented investment the administration plans to build on by bringing in additional public dollars and trading on the value of city land and assets.

Under the proposal, 13,500 units would be newly constructed and 16,500 would be preserved.

The majority of those units would be affordable to households earning less than $100,000 a year. And more than 20,000 units would serve families earning about half that amount.

During Wednesday’s hearing, some lawmakers questioned whether the proposal does enough to help the city’s lowest-income residents — households earning less than $31,000 a year.

The administration’s proposal, guided by creating “economic opportunity for all,” seeks to create or preserve a total of 9,000 units over four years. Councilmember Rue Landau said while she overall supports the administration’s plan, she wants to see more resources go towards helping the city’s poorest residents amid an ongoing affordable housing crisis.

Nearly a third of Philadelphia households — about 200,000 families — earn less than $30,000 a year, according to the Pew Charitable Trusts.

“That’s where I want the largest investment of funding to go — the have-nots and the have-a-littles,” said Landau. “It’s the higher levels that are a little more concern to me.”

Jessie Lawrence, who directs the Department of Planning and Development, told lawmakers the H.O.M.E. initiative is rooted in creating “economic opportunity at all income levels” — not just those at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder.

That includes working class residents struggling to buy their first home and existing homeowners struggling to make needed repairs on their aging properties.

“We’re trying to provide some kind of upward mobility, not just for those at the lower incomes but also at the moderate incomes as well,” said Lawrence. “That’s the administration’s approach — growing the pie.”

Officials also argued that Philadelphia Housing Authority is better equipped to provide housing to the city’s lowest-income residents, and that the agency has already launched an ambitious effort to that end — the “Opening Doors” initiative. Under the $6.3 billion initiative, PHA will preserve, redevelop, build or acquire about 20,000 units, all of which will be heavily subsidized.

‘Hit the ground running’

If the administration’s proposal is approved, a majority of the $800 million would be spent on a handful of initiatives and programs, including ones dedicated to affordable housing preservation and production, workforce housing projects and home repair initiatives.

The plan, for example, seeks to expand the eligibility for the Basic Systems Repair Program, easily one of the city’s most popular initiatives.

The program, which provides free home repairs, is available to households earning up to 60% of the area median income, a regional statistic that translates to $68,820 for a family of four. Parker wants to offer the program to households earning 100% of the area median income, which translates to $114,700.

Under the proposed expansion, the program is projected to serve 7,500 households during the life of the H.O.M.E. initiative. Dave Thomas, president of the Philadelphia Housing Development Corporation, said the current waiting list for the program is about 8,000 strong.

The administration also wants to ramp up the city’s Turn the Key program. The goal is to build another 280 homes on city-owned land and clear the program’s backlog, which contains about 800 projects.

Turn the Key utilizes properties part of the Philadelphia Land Bank, a public agency created more than a decade ago to help put vacant land into productive use. Most parcels in the land bank are transferred to private developers for affordable housing projects.

“The mayor wants to put Turn the Key on steroids,” said Tiffany Thurman, the mayor’s chief of staff, during Wednesday’s hearing.

In service of that goal, the administration’s proposal seeks to improve the land bank’s disposition process, which critics have said has seriously hampered the agency by being too obscure, too complex and too lengthy. That task will start with a third-party consultant conducting an operational assessment of the land bank’s procedures, which could take months to complete.

Council President Kenyatta Johnson raised concerns about the assessment slowing housing production under the initiative, which Parker has repeatedly said is an immediate priority of the plan. He also questioned why the land bank assessment hadn’t been initiated last year, given the critical role the agency is set to play in the administration’s housing plan.

“We probably should have already hit the ground running,” Johnson said. “But yes, we can walk and chew bubble gum.”

Thurman insisted the assessment would take less than a year, and that it is meant to “enhance” and “improve” things, not delay. The administration, she added, was not in a position to conduct the assessment until now.

“The government we walked into last year was not ready to do that,” Thurman said.

The H.O.M.E. proposal includes nearly 40 programs and initiatives, about half of which are brand new.

The administration is calling on Council to approve the H.O.M.E. initiative in tandem with the city’s next budget, which is expected to cost upwards of $7 billion.

The goal is to approve both plans before the next fiscal year starts on July 1.

Finance Director Rob Dubow has said the city would borrow the $800 million in two equal chunks, with the first tranche likely coming sometime this fall and the second slated for 2027.

Dubow said Wednesday that the “overall assumption” is that the first dollars will go toward existing programs, and that the funding for new ones would come next July.

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.