Corporate investors bought a quarter of Philly’s single-family homes sold over 6 years. Here’s what that means amid a tight housing market

A new study finds investors are snapping up properties in neighborhoods like Germantown and Cobbs Creek — and it could change who can afford to live there.

Listen 1:28

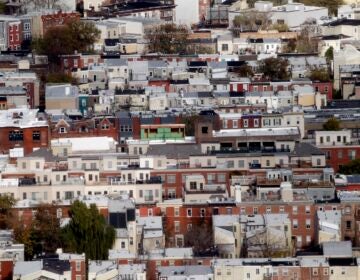

Homes in the Cobbs Creek section of Philadelphia. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Have a question about Philly’s neighborhoods or the systems that shape them? PlanPhilly reporters want to hear from you! Ask us a question or send us a story idea you think we should cover.

Corporate investors in Philadelphia are most active in predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods with cheap real estate, and often operate as landlords instead of house flippers or developers, according to research published by the Reinvestment Fund.

The report, released Monday, focuses on single-family homes sold between 2017 and 2022, the last year for which data is available. Emily Dowdall, president of policy solutions at the nonprofit, said the data highlights the potential pitfalls of these purchases, which accounted for about a quarter of all single-family home sales. This includes the potential for decreased affordability and “crowding out” first-time and lower-income homebuyers.

Philadelphia’s homeownership rate is about 52%, according to The Pew Charitable Trusts.

“Because affordable home ownership has been such an important part of Philadelphia’s identity, it does, in a sense, lead to a bit of an identity crisis of what kind of city are we if we’re not offering that upward mobility or just even generational stability for folks to own a piece of their neighborhood,” Dowdall said.

Previous reports investigated where corporate investors are buying single-family homes, how much they typically spend acquiring those properties, and how active they are in the city’s housing market. But this is the first report to identify these investors and detail what they’re doing with properties they’ve purchased, typically through a limited liability company.

The research, conducted in partnership with Rutgers Law School and the Housing Initiative at Penn, found that large and small investors were more likely to have code violations than homeowners. Large corporate investors were also more likely to file for an eviction compared to smaller investors.

Researchers defined small investors as companies that purchased fewer than 100 properties.

“This is by no means all investors, but there are some investor models that heavily rely on evictions and filing evictions just to collect rent,” Dowdall said. “Once a person has one eviction, it can be really destabilizing for a lot of other reasons — financially and in their life in general.”

Evictions typically make it harder for tenants to secure safe and affordable housing in the future because, at the moment, that record cannot be sealed. And all things being equal, a landlord is more likely to reject someone with a filing on their record, even if it didn’t result in a lockout. In Philadelphia, Black mothers are the most likely to face an eviction.

‘We are struggling to hold the line’

Rodney Willis, a former mortgage banker and landlord, has lived in Cobbs Creek for decades. For most of that time, his neighborhood saw little to no private investment, even as nearby parts of West Philadelphia did.

That’s no longer the case, and it’s instilling panic that his neighborhood, long a bastion of Black homeownership, will change for the worse.

Just in the last 18 months, Willis has watched eight properties on sale on his block. That type of activity, he said, has the power to disrupt the community’s fabric forever.

“When homeowners are not the majority, a lot of things start to go sideways,” Willis said. “We are struggling to hold the line.”

Fellow block captain Vandelyn Waring is worried the corporate investments in her neighborhood will decrease affordability and increase property taxes, potentially displacing longtime residents and creating a barrier for others.

“The interest in Cobbs Creek is a great thing , but it is a problem for residents who have been here for a very long time and even newer working class, middle class individuals who want to live here and can’t afford to live here,” said Waring, a Philadelphia native who moved to Cobbs Creek about six years ago. “It’s extremely heartbreaking to see what is happening.”

Across the city in Brewerytown, renter Claire Newsome is wary that corporate investors are driving discontent among her neighbors. She said these landlords are less likely to be invested in the community’s well-being and more likely to poorly manage the properties.

The combination, she said, sits at the heart of the complaints tenants lodge against their landlord, who are often more difficult to get in touch with than small landlords.

“There’s a level of accountability that’s removed from when you have one person who is managing a couple properties themselves,” said Newsome, equitable housing lead at the Brewerytown Sharswood Neighborhood Coalition.

Corporate investors bring opportunities and pitfalls

The report does highlight some positives.

Most of Philadelphia’s housing stock was built before 1960, and thousands of those properties are in need of significant repairs, which individual property owners may be unable to afford. Researchers found that small and large corporate investors sought permits for repair work at a higher rate than individual homebuyers, indicating that some of these companies renovated and upgraded the properties in order to rent out.

Over the six years of the study, investors were most active in about a dozen neighborhoods across the city, including Brewerytown, Germantown, Parkside and parts of Cobbs Creek.

Larger investors also secured rental licenses at a slightly higher rate than the city average, with high-volume companies generally leasing their properties to lower-income tenants. Unlicensed landlords are more likely not to have a business license, making it very difficult to know if they are providing safe and habitable housing.

Philip Balderston, CEO of Odin Properties, said corporate investors help provide the city with much-needed rental housing, especially for residents who can’t afford to become homeowners. He said those dollars also allow the city to invest in helping homeowners maintain their properties, one of the major planks of Mayor Cherelle Parker’s signature housing plan.

Balderston’s company bought nearly 160 single-family homes between 2017 and 2019. He has since sold all of them to focus on building new affordable units, including a government-backed project in North Philadelphia.

Many of the homes were purchased by other corporate buyers who acquired a package of properties to maintain as rentals.

“Individuals who are looking for homes in those neighborhoods when they’re for sale, those individuals are purchasing those homes,” Balderston said. “Corporate entities generally don’t come in and purchase vacant homes and then rent them. It’s not easily financeable and it doesn’t make investment sense generally.”

The report recommends a series of policy and regulatory interventions aimed at increasing transparency and accountability, as well as leveling the playing field for individual buyers.

For now, it can be very difficult to figure out who owns a corporate property, making it hard for renters and local governments to identify who they should contact when there’s a problem, especially if the outfit isn’t local.

Researchers say local lawmakers should develop legislation requiring companies with corporate rental properties to disclose the details of that ownership.

They are also pushing for enhanced enforcement, particularly around rental licenses, and for nonprofits and individuals to have priority at sheriff sales, where it is common for corporate investors to buy single-family homes. That status, currently afforded only to the Philadelphia Land Bank, would enable these groups to make noncompetitive bids on tax-delinquent properties. Those properties would otherwise go to the highest bidder.

“We do think it’s important that investments are getting made in neighborhoods. But it’s up to officials to try and mitigate any negative consequences of those investments as well as promote some of the positive aspects of development and investment in order to stabilize neighborhoods,” Dowdall said.

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.