To die for: The Science History Institute shows us how we dye

A new exhibition at the Science History Institute, BOLD, tracks the cultural and environmental impacts of synthetic dyes.

Listen 2:57

Synthetic dyes made fashion more vivid, like this hot pink miniskirt suit, designed by Ben Zuckerman in 1964. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

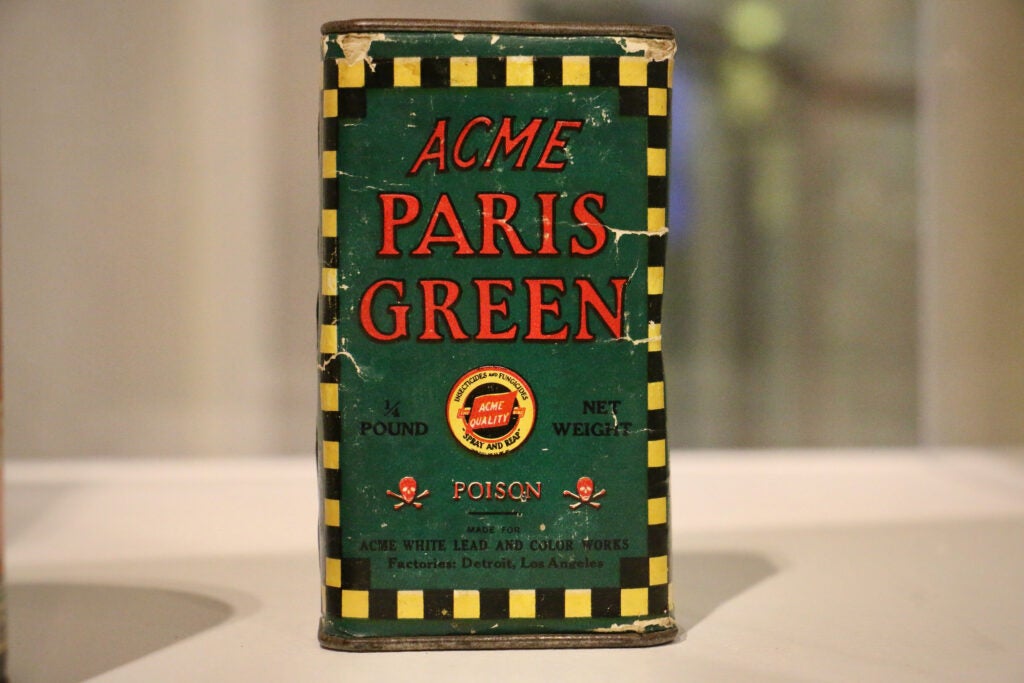

In 1864 Princess Eugenie of France attended the Paris Opera wearing a dress of such vibrant green that it made the newspapers the next day. It was a color that had not been possible through natural dyes, only by a new synthetic dye that would later be called Paris Green. It became a fashion rage.

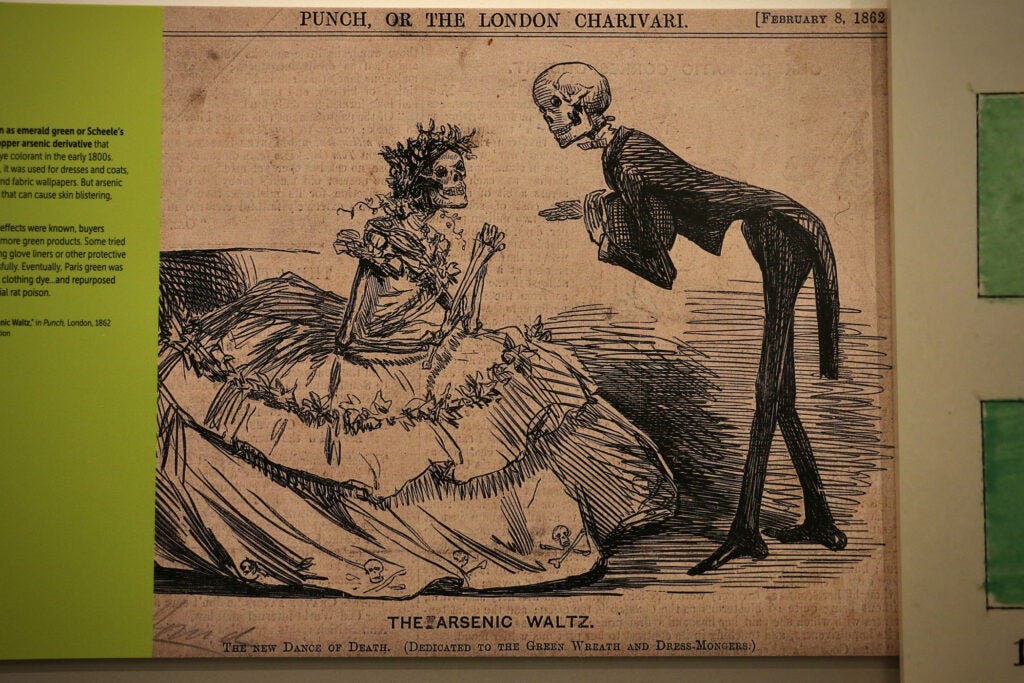

Unfortunately, Paris Green contained arsenic, which poisoned laborers in textile factories and even wearers of green clothes. It was also used to color wallpaper and bookbindings.

When it became understood that green clothes were causing sickness and skin lesions, and even death, some fashionistas decided they were OK with that: the color was so compelling they found ways to mitigate the risk.

“If I sweat in the green dress, I’ll vomit. So I’ll only wear it when it’s cold out and I won’t sweat,” said Elizabeth Berry Drago, a curator at the Science History Institute in Philadelphia, describing justifications for wearing clothes dyed with arsenic. “We found out that it gives me rashes on my fingers: I’ll wear glove liners.”

“Talk about an illustration of how powerful color is culturally,” she said. “This color is fashionable so people don’t immediately get rid of it.”

Ultimately, Paris Green would be discontinued as a pigment, and re-branded as an insecticide. It got its name not for its royal debut at the Paris Opera, but because it was used to kill rats in the Paris sewer.

Drago curated “BOLD: Color from Test Tube to Textile” at the Science History Institute, an exhibition tracking the scientific and cultural revolution created by synthetic dyes, including their impact on Philadelphia, once a major hub of the textile industry.

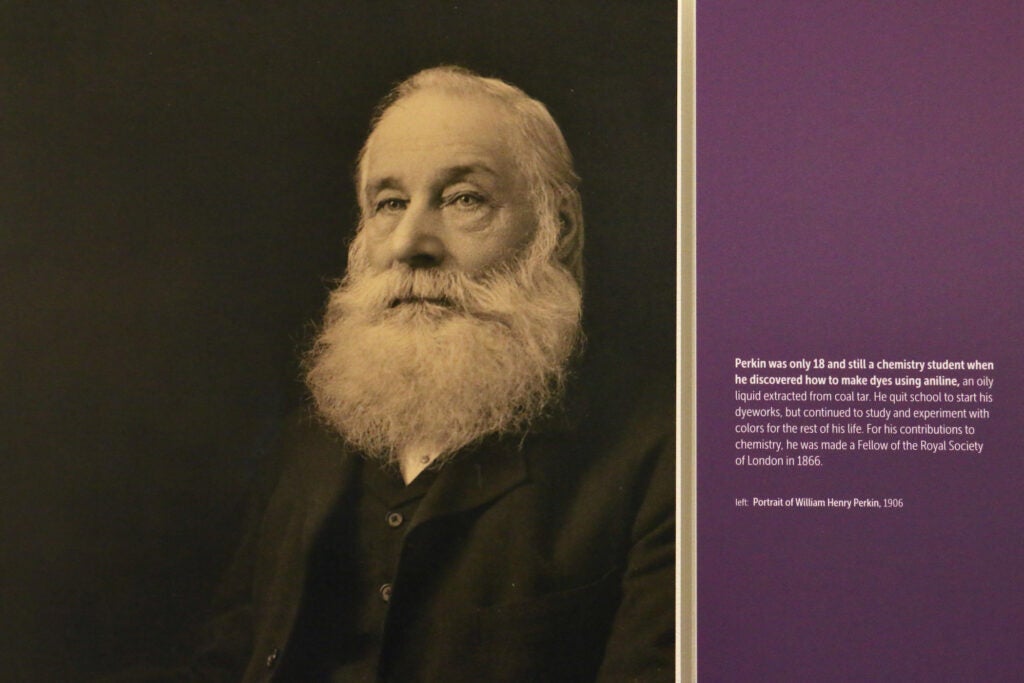

The first synthetic dye was discovered accidentally. In 1864 an 18-year-old chemist was trying to tease quinine out of coal tar, a black sludge byproduct of coal production. William Perkin discovered his test tubes had turned mauve, a color that had never before been possible in textiles.

Perkin abandoned his quest for quinine and introduced mauve as a commercial dye, which caused a sensation. As more synthetic dyes were developed they offered seemingly unlimited color variations.

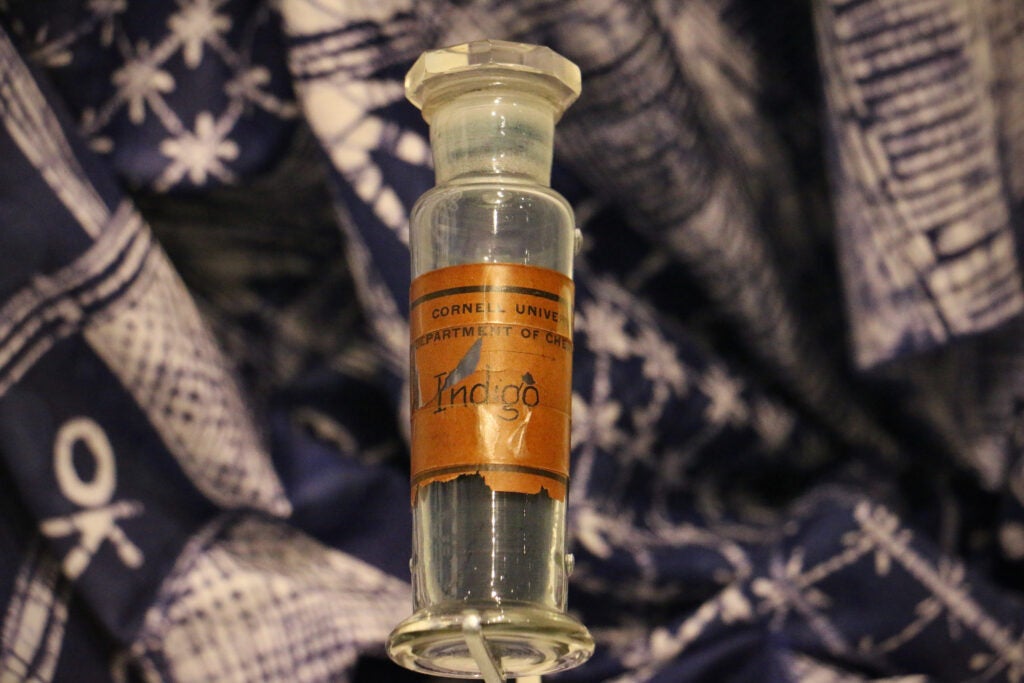

“We don’t have every color of the rainbow when it comes to natural dying. There’s saffron for yellow. There’s indigo for blue. There’s a madder for soft reds,” said Drago. “One of my favorite obscure pieces of colonialism trivia: Brazil is named for Brazilwood dye.”

Brazilwood, a native tree to what is now Brazil, was highly prized for its ability to produce a vibrant red pigment. It is named after the Portuguese word for a red glowing ember, “brasa,” and in the 16th century they exported so much of it they named the region after that color.

In the United States the indigo flower became an important commodity crop to make blue dye; it was mostly grown on Southern plantations and often by enslaved people. The petals must be collected by the tens of thousands, fermented for a long period of time to make a dyeing vat, and the dyed fabric will only become blue after a period of oxidation. The process of turning something blue could take months.

Synthetics changed all that.

“Dyeing was always a technology, and then synthetics accelerated that. It becomes this highly technological process that builds the whole chemical industry,” said Drago. “All the firms that we think of as powerhouses in chemistry, medicine, and pharmaceuticals, they often start as dye companies. Bayer starts as a dye company. Novartis starts as a dye company.”

Much of that dyeing happened in Philadelphia. At the turn of the century, when the city called itself The Workshop of the World, Philadelphia was the world’s leader in textile production, with about 700 companies related to the industry, employing about 60,000 people.

Most of those companies are no longer active. One of the last remaining dye works from that era is Caledonian Dye Works in Kensington, founded in 1911 and now a fourth-generation family business that dyes material mostly used in the home furnishing and the hospitality industries.

“Hair nets,” said Kimberly Livingston, the current owner of the company and the great-granddaughter of its founder. “You still need to dye hair nets.”

The local textile industry was once so entrenched in Philadelphia cultural life it hosted an annual “Wool Week” for companies to show off their work to the public. There was even a textile parade, with floats.

Livingston said it was easier to do business when the competition was across the street.

“You have generations of families that know each other and went to meetings together, like the Master Dyers Association,” she said. “You could call up and say, ‘Hey, I’ve run out of Glauber’s salt and we’re not due to get our truck shipment in until, you know, Tuesday. Could you run a couple bags over?’ We had all realized many years ago that in order to keep the textile industry alive and well, we needed to help each other out.”

Most dye factories were located along Philadelphia’s rivers because the process requires a tremendous amount of water. The Globe Dye Works compound was near Frankford Creek feeding into the Delaware River. The building, now a mixed-use residential and artisan development, still has the original sign on the roof like a neighborhood beacon.

Dexter Mill and Dye Works was built in the late 19th century in Manayunk so its factory could pull water directly from the canal and send wastewater back out again. The synthetic dyeing process uses a huge amount of salt and various corrosive chemicals, and turns wastewater dark. That likely contributed to the degradation of Philadelphia’s watershed in the early 20th century.

“When a water source is colored, it impedes the ability of light to penetrate,” said Becky Flax, a professor of textile design at Thomas Jefferson University. “All of the plants that are underwater are not able to photosynthesize properly. The plants die and the animals die and it just shuts everything down.”

The exhibition BOLD shows the darker side of dyeing: in the early 1930s so many textile workers at DuPont in Wilmington, Del., were diagnosed with bladder cancer that doctors held a symposium on the subject in 1934, determining that the dyeing industry was a “cancer cluster.”

Nevertheless synthetics, both dyes and fabrics, came to dominate the textile industry. At the 1940 New York World’s Fair, the DuPont company introduced the Test Tube Girl, aka the Chemical Girl, a campaign featuring a young lady outfitted entirely in synthetic fibers, from her cellulose hat down to her rayon dress, nylon pantyhose, and Lucite shoes.

The BOLD exhibition features artifacts from the color revolution: a woman’s Barbie-pink suit, a 1968 advertisement for Maidenform underwear in “super blue, super pink, and super citrus green,” an aggressively patterned 1960s underwear set by the Italian designer Emilio Pucci, known as the Prince of Prints. All were possible because of synthetic fabrics and dyes.

“I did not know about the Barbie movie when we were conceiving this,” Drago promised. “I did not know Margot Robbie was gonna wear Pucci on the runway promoting the Barbie movie, but she did.”

Synthetic dyes changed how people could participate in fashion. Home-dying products introduced during World War One, like Rit and Tintex, gave average people the chance to refresh their old clothes with modern color tastes.

Color, the exhibition argues, is fun. On the walls are lyrics from a song by the 1970s punk band X-Ray Specs, “The Day the World Turned Day-Glo.”

“Part of the problem that we experienced in the ‘40s and ‘50s when all of these new things came on to the market, was that they just ramped up production without really knowing the full impact of everything,” said Flax. “We now see different impacts, thinking through the entire life cycle of what you intend to make.”

Flax said many of her students at Thomas Jefferson University are returning to natural dyeing processes in their textile design work. That trend is reflected in the BOLD exhibition, which spotlights the Lancaster, Pa., company Green Matters Natural Dye Company, which uses natural dyeing techniques for clients such as Chipotle and Stitch Fix. The company also offers a community indigo vat, where people can mail their individual articles of clothing to be dyed blue together in one big batch.

Drago believes the color blue could become a tipping point for the textile industry. Along with t-shirts and sneakers, blue jeans are the single most consumed article of clothing in the world. They are dyed indigo, which is a tricky color: in order to fix indigo into fibers it needs a reductive agent, typically sodium hydrosulfite, a corrosive chemical that burns skin and is potentially combustible. The New Jersey Department of Health lists sodium hydrosulfite as a Special Health Hazardous Substance.

“When you think about trying to make an impact on sustainability, jeans are a great method in. If you could change the way that one garment is dyed, it would have to be synthetic indigo,” Drago said. “If you could change the denim industry, you can change the whole global textile industry.”

Livingston, at Caledonian, has been experimenting with using natural dyes on an industrial level, and learned to proceed with caution. A recent trial using dyes derived from black walnut in her factory equipment was a failure.

“It’s very difficult to clean it off stainless steel and gaskets, to the point where we had to pull apart a machine and change every seal and every gasket,” she said. “It’s just not meant for industrial uses like that. It’s more meant for very small batches.”

Industry regulations are much more stringent now than in the early days of dyeing. Dye manufacturers are required to comply with certain environmental rules, and the Philadelphia Water Department maintains higher standards of industrial wastewater, testing factories monthly. Caledonian, for example, has been recognized by the Water Department for consistently passing inspections year-over-year.

In other places, the textile industry continues to cause significant environmental damage: Indonesia’s Citarum River, near Jakarta, is considered one of the most polluted in the world. There are an estimated 2,000 industrial sites dumping wastewater into the river, including about 200 textile factories.

Flax, at Thomas Jefferson University, has her eye not just on dyes but fabric finishers. She points out that the methods used to achieve permanent press clothes, or durable press (DP), often incorporate formaldehyde.

“I’d like my shirt to be worn day to day and not wrinkle, not have to iron it, but those DP finishes are not good,” she said. “But I think we’re willing to suffer for fashion.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.