Rise in residential development in Germantown sparks optimism — and caution

For decades, Germantown was not the kind of place developers held ribbon-cutting ceremonies. But that’s changing.

Have a question about Philly’s neighborhoods or the systems that shape them? PlanPhilly reporters want to hear from you! Ask us a question or send us a story idea you think we should cover.

On a brisk December morning, Philip Balderston wore a black overcoat and a wide smile as he stood inside an unfinished commercial space in Germantown.

Balderston, founder and CEO of Odin Properties, came to the neighborhood to cut the ribbon on a pair of modern apartment buildings on Germantown Avenue. They have high ceilings, granite countertops, and stainless steel appliances. One of the properties has a rooftop lounge.

“It’s a great neighborhood for us because of its history, because of its people, because of its thriving small business, and of course because of the location. We’re just a stone’s throw from Center City,” Balderston told the bundled group before him.

He said residential density is key to driving positive change in Germantown.

“The more apartments you have in Germantown, especially kind of high quality and affordable, the more retail activity you’re gonna have on Germantown Avenue. That’s going to increase opportunities for small business and that’s going to kind of enrich the community,” said Balderson.

The weekday ceremony was brief but significant.

For decades, few private developers wanted to invest in Germantown — a predominantly Black, family-friendly community with a high poverty rate and its fair share of blight. Until recently, a single company was behind most of the major developments in the neighborhood.

That’s no longer the case.

Over the last few years, Germantown has experienced a wave of residential construction that’s seen at least a dozen developers enter the market, a multimillion-dollar shift that’s become a hot topic of conversation among residents. While some think the influx has the potential to improve Germantown, others find the rate of new development alarming and fear swift gentrification is well on its way.

“It’s rapid,” said neighborhood activist Rosalind McKelvey. “You drive around and go ‘Oh my gosh. When did that go up?’”

Cautious optimism

Odin’s new apartment buildings sit near the commercial heart of Germantown, about a 20-minute drive from City Hall. Each building has 47 units. Most are one- and two-bedrooms with monthly rents Balderston calls “value-oriented” — attainable for residents earning 80% of the area median income. In 2022, that translated to $75,900 for a family of three.

One-bedroom apartments range between $1,300 and $1,400 a month, while tenants are paying $1,600 to $1,900 for a two-bedroom place, depending on the size. Vernon Lofts is an adaptive reuse project that fills the former C.A. Rowell Department Store, the country’s first Black-owned department store. Kenyon Lofts is a brand new development built on top of an old parking lot.

For Larry and Stacey Henry, Kenyon Lofts was a perfect fit.

For nearly 20 years, the couple lived in a three-bedroom house in nearby Roxborough. They loved their time there, but were ready to downsize once they became empty nesters.

“Our age had a big thing to do with it. Got tired of cutting grass and things like that. So we just wanted to try to move where we didn’t have to keep up with the upkeep of the property and could just try to enjoy the last few years of our golden years,” said Larry Henry, 62.

“It was time for a new chapter,” added Stacey Henry.

The couple also has ties to Germantown. Stacey is a longtime member of a church in the neighborhood. Larry grew up close by, making the move a “full circle” moment for him.

And while the neighborhood of 47,000-plus is changing, Larry said he doesn’t find the development “overwhelming” the way it did in Roxborough, which also has seen a surge in development.

Most of the projects built or planned for Germantown are by-right apartment buildings offering studios, one-bedrooms and two-bedrooms, meaning they don’t require any zoning approvals for construction to start. Since 2019, at least 400 units have come online, according to commercial real estate giant CoStar. That total is expected to more than double in 2025.

The majority of the new developments are ground-up construction, but the list does include some renovations of existing properties, including Vernon Lofts. Developers are also transforming Germantown High School into a 240-unit apartment building with ground floor commercial space. The vacant property is one of three neighborhood landmarks residents have desperately wanted developers to revive.

“It just makes us look blighted and failed,” said community activist Yvonne Haskins in May.

The developments are largely clustered around Germantown Avenue or located in West Germantown, where there is generally more wealth and less crime compared to other parts of the neighborhood.

Most of the projects are going up on what was underutilized or vacant land.

Ken Weinstein, who leads Philly Office Retail, largely welcomes the company after years of being one of the only private developers investing in the neighborhood. Most recently, his company bought an old factory building as part of a $56 million revitalization plan launched more than a decade ago to breathe new life into the blocks in and around SEPTA’s Wayne Junction Station.

“We’re seeing property values increase slowly. We’re seeing rents increase slowly. And that is resulting in less blight in Germantown, which is what we’re after,” said Weinstein, who started investing in the neighborhood nearly 40 years ago.

He’s cautiously optimistic that Germantown can avoid the kind of rapid gentrification other neighborhoods like Northern Liberties and University City have experienced.

“It sounds kind of weird for a developer to say that, but I am not in favor of fast explosive growth because that’s what results in displacement,” said Weinstein. “We’re looking for continued slow steady growth and I believe that’s possible here in Germantown.”

Cause for concern

Between 2012 and 2022, the median sale price for a home in Germantown jumped 142% to $184,000, in part because people were seeking larger homes with work space during the pandemic.

And while today there are some outliers, many of the homes currently listed for sale in Germantown are still priced below the city median of $235,000. At the same time, census data shows the neighborhood’s racial demographics have remained largely unchanged despite a rise in population between 2015 and 2022. Black residents still make up more than 70% of Germantown’s population.

“What we’re seeing in Germantown is that there’s reinvestment in the housing stock and some stabilizing home values, but without a major shift in the types of people who are able to access the neighborhood,” said Emily Dowdall, president of policy solutions at the Reinvestment Fund.

Neighbors like Rosalind McKelvey still see cause for concern. The multifamily buildings she sees popping up around the neighborhood are a big reason why. To her, they signal a troubling shift away from the core of Germantown’s population: families.

McKelvey, who has lived in Germantown for 40 years, said adding smaller apartments won’t spur the kind of neighborhood improvement longtime residents want to see. It also bothers her that existing homeowners aren’t getting the help they need to fix up and maintain their properties, at the same time private developers are putting up brand new apartment buildings seemingly geared towards students and young professionals.

“It doesn’t encourage growth. It doesn’t encourage unity,” said McKelvey.

Douglas Rucker, executive director of the Chew and Chelten CDC, agreed. In an effort to keep homeowners in the neighborhood, he’s taking pains to encourage neighbors in his section not to sell, especially when they receive offers, something he said is happening a lot more these days.

“To avoid some of the displacement and whatever else comes with gentrification, it calls for community involvement. If you sit there dormant, they’ll walk right over you, and then who’s to blame?” said Rucker. “We have to put some type of limit to it where we too can coexist in our own community.”

That spirit of preservation is part of what drove a successful campaign to create a new historic district. Awarded in February, the designation protects from demolition dozens of properties spanning more than 250 years of Germantown history — from its colonial roots through its days as an industrial epicenter.

The Philadelphia Historical Commission will also have to review the designs for any new developments proposed for the district, a partial check on the rise of residential projects.

“That’s how most places get protected is when they become threatened,” said historic preservationist Oscar Beisert, who wrote the nomination for the district.

Back in business

If there’s a potential silver lining for concerned residents, it’s that the increased development activity could help improve the neighborhood’s struggling commercial corridors — by delivering more disposable income and foot traffic.

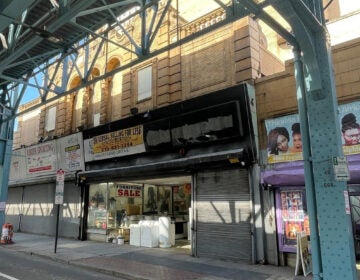

During the early part of the 20th century, Germantown’s central business district was the second-largest shopping district in Philadelphia outside of Center City. But by the 1970s, the district was a shell of its former self as Germantown lost population to the suburbs. Malls soon made matters worse.

As of last summer, the district’s vacancy rate sat at 18%, according to data provided to the city’s Commerce Department. That translates to 50 out of 282 storefronts. A 5% vacancy rate is generally considered to be “healthy” for a busy retail corridor.

Emaleigh Doley, executive director of Germantown United CDC, said an influx of residential development, particularly around the business district, could potentially change those fortunes if the additional density motivates new businesses to open up shop.

The district, for example, has a dearth of sit-down restaurants, particularly ones serving dinner.

“We have a lot of financial loss where people living in Germantown are spending all or the majority of their money outside of the neighborhood. So we can potentially see a better and healthier, more local economy with growth in the business corridor,” said Doley, who has called Germantown home for much of her life.

That reality is a big reason why longtime resident Villia Abdul-Lateef is thrilled that Weavers Way Co-op is opening one of its markets on Chelten Avenue. Abdul-Lateef, an education specialist in Delaware County, typically drives to Chinatown or the Reading Terminal on her way home from work to get groceries. While she’s down there, she sometimes hits retail shops in Center City before returning to Germantown.

“And I just keep saying, ‘I just want to do this in my own community,’” said Abdul-Lateef.

When she looks at all the new apartment buildings in her neighborhood, she sees the potential for positive change — even as she continues to get offers for her home, even after she watched three neighbors on her block move out because their landlord raised the rent beyond what they could afford.

And she thinks the neighborhood has room to grow, especially when it comes to its commercial corridors.

“I’m trying to just hopefully see where this goes. I would love to see this keep going forward,” said Abdul-Lateef. “I’m hoping not at the expense of people leaving.”

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.