A Philly family shares its huge collection of art by Dox Thrash

The renowned printmaker had befriended a blind boy from the neighborhood in North Philly. Now his descendants keep Thrash’s legacy alive.

Mark Rollins leads the McIntosh Rollins Foundation, which manages the collection of his great aunt, Esther Rollins McIntosh, who died in 2014. Her living room, including the Dox Thrash painting, ''Driftwood,'' is recreated in the Fleisher Art Memorial exhibit, ''Dox to Light: The Life and Works of Dox Thrash.''(Emma Lee/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Sometime in the 1940s in Philadelphia, the artist Dox Thrash met a boy who was blind named David McIntosh. Despite being 32 years apart, the two became lifelong friends.

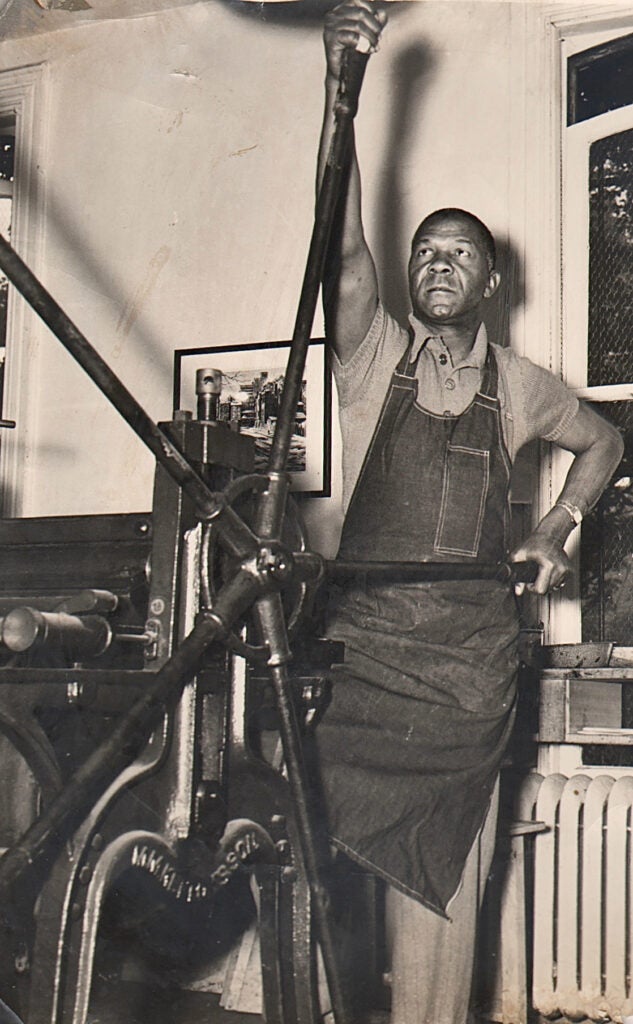

Thrash was a celebrated printmaker who developed an innovative printing process and was one of the few Black artists to join the Depression-era Works Progress Administration. His work tended to focus on the Black communities he was part of.

McIntosh, blind since childhood, grew up to earn a master’s degree from the University of Pennsylvania, and would rent studio space to Thrash. Although he was never able to see the artwork that has made Thrash renowned, the two hit it off.

“One of the amazing things is how he had this relationship with this fantastic visual artist who sort of mentored him, and gave him sight,” Rollins said. “We think Thrash thrived on that, also.”

That decades-long friendship is at the heart of “Dox to Light: The Life and Work of Dox Thrash,” now on view at Fleisher Art Memorial in South Philadelphia.

The relationship expanded when McIntosh married Dr. Esther Rollins. They shared a building at 2313 Ridge Avenue, a building that no longer exists. McIntosh ran a barber and beauty supply shop on the ground floor, Rollins ran her psychology practice on the second floor, and Thrash shared a studio on the third floor with fellow artist Samuel Joseph Brown.

That building was not Thrash’s home, which was at 2340 Cecil B. Moore, where a group of preservationists and a community development organization are currently attempting to renovate the space as a neighborhood cultural center. The Thrash house is in the vicinity of other historic houses of important Black artists, John Coltrane and Henry Ossawa Tanner, which are also the focus of efforts to preserve and maintain them as historic sites.

Through their relationship with Thrash, McIntosh and Rollins bought or were gifted over 420 drawings, paintings, and prints by Thrash, from large oil paintings to small portraits quickly sketched on scraps of paper shopping bags. It is the largest known collection of works by Thrash.

McIntosh died in 1972. After his wife Esther died in 2016, their descendants created the McIntosh Rollins foundation, for the purpose of maintaining and making available the Thrash collection.

“Dox to Light” is that foundation’s first exhibition, featuring 41 pieces now on view at the Fleisher Art Memorial in South Philadelphia, where Thrash used to take classes and make prints. The exhibition highlights pieces that were personal favorites of Esther Rollins.

“She had a select group of things that she wanted to live and see all the time when she navigated her house,” Rollins said. “She had her friends on the wall, her identity.”

The exhibition came to Fleisher through Ron Rumford, the director of Dolan/Maxwell gallery in Philadelphia specializing in prints and works on paper. Esther had contacted him years ago to assess the collection and offer professional advice.

“For me, doing what I do, it was wonderful to walk into a house where there was somebody living with art,” Rumford said. “In this case it was one artist, a very good, very important artist.”

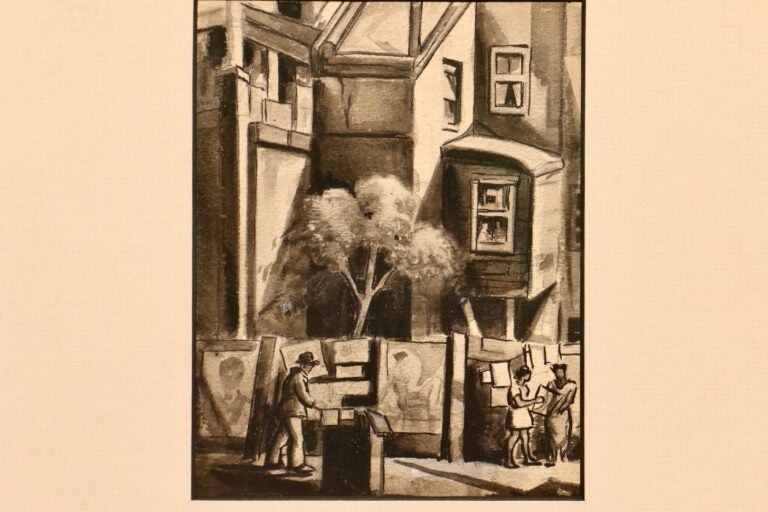

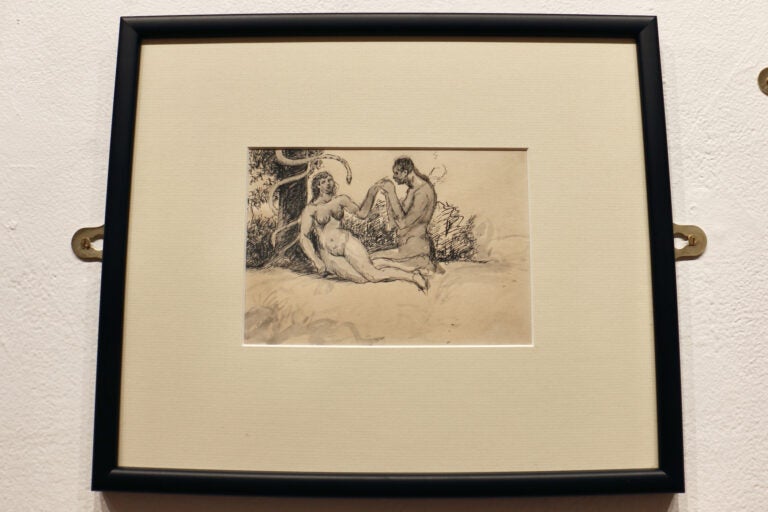

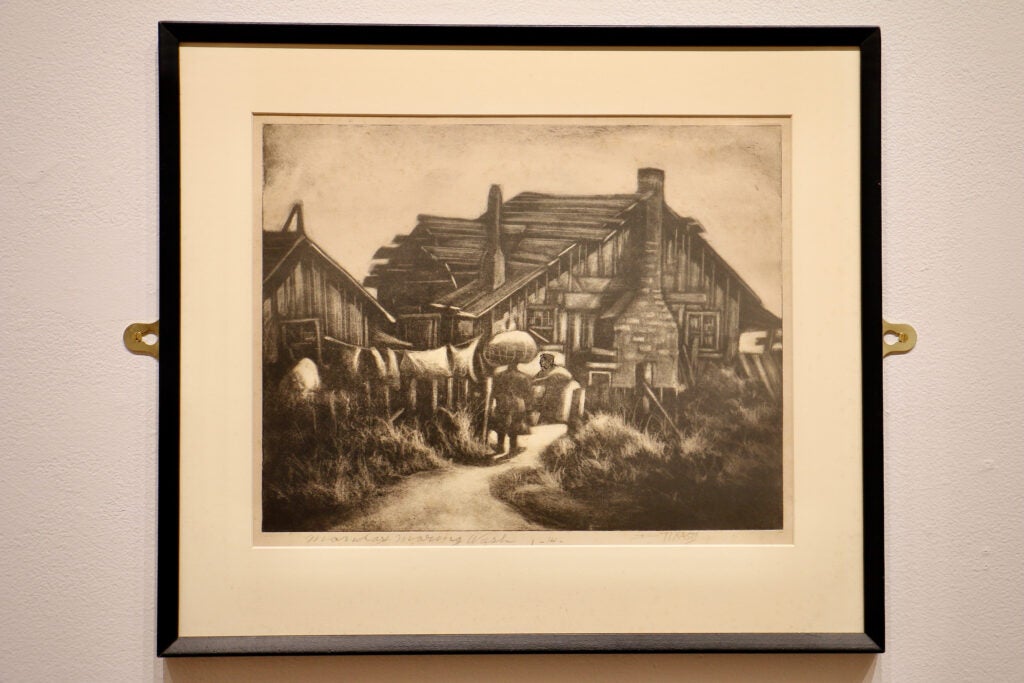

The exhibition features some of Thrash’s largest works using the carborundum mezzotint printing method, which he invented in the 1930s by grinding silica crystals into certain portions of the metal printing plate. When inked, it would create subtleties of tone and softer lines.

On view are portraits of people he knew (and some he likely did not), prints of Philadelphia scenes, including City Hall and Ridge Avenue storefronts, and rural scenes he recalled from his childhood growing up in Georgia. “Monday Morning Wash” (1937), one of his largest and most ambitious carborundum mezzotint works, features laundry strung in front of a house he likely would have seen in Griffin, Georgia, his hometown.

“He didn’t forget where he was from,” Rumford said. “He is kind of ahead of the Great Migration. He goes to Chicago in the teens as a very young man. He served in World War I as one of the Buffalo Soldiers in France. He was gassed at the very end of the war. Part of his recovery was going to the Art Institute of Chicago.”

After Chicago, Thrash traveled around, landing in Philadelphia where he worked a variety of jobs, including as a janitor and in a shipbuilding dock. This was where he started working for the Works Progress Administration and joined the Pyramid Club, an elite Black social club of the time.

“I think he stayed here because Fleisher was here,” said Rumford. “He realized printmaking was the best way for him to express who he was as an artist and as a human being. That was here and he had the mentorship of a very highly regarded artist, Earl Horter.”

“Dox to Light” is part of Fleisher Art Memorial’s 125th anniversary events. The center started hosting free art classes in South Philadelphia in 1898, ultimately moving into the current hive of four buildings cobbled together on Catherine Street, including a former church and school for indigent boys. It offers classes, workshops, and exhibitions for children and amateur and professional artists in a wide variety of mediums.

“I think this exhibition is so perfectly Fleisher,” said director Monica Zimmerman. “You see in just Dox’s story the idea of Fleisher as a place people go to when the rest of the world isn’t always safe,” she said. “A place where people are perpetual students.”

“Dox to Light” will be on view at Fleisher Art Memorial until Nov. 17.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.