An Iranian arts festival was condemned by a fatwa 45 years ago. Its impact is now on view at Asian Arts Initiative

A groundbreaking Iranian cultural event fell to the Islamic Revolution. Now, the Philly arts center is remembering the Shiraz International Arts Fest.

Listen 1:13

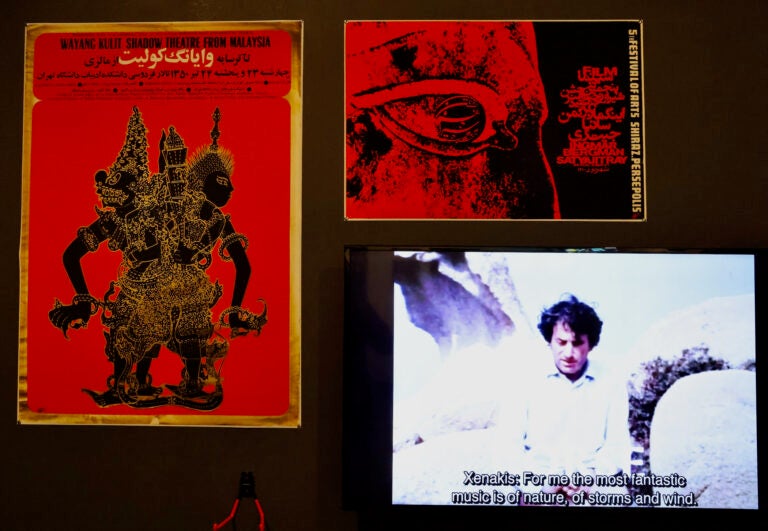

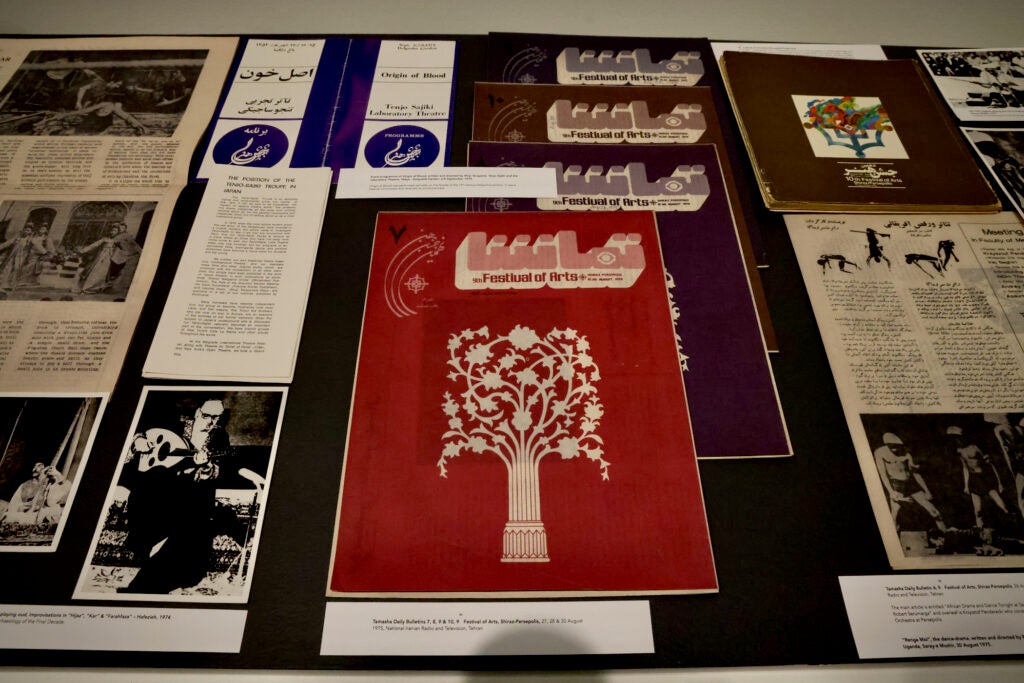

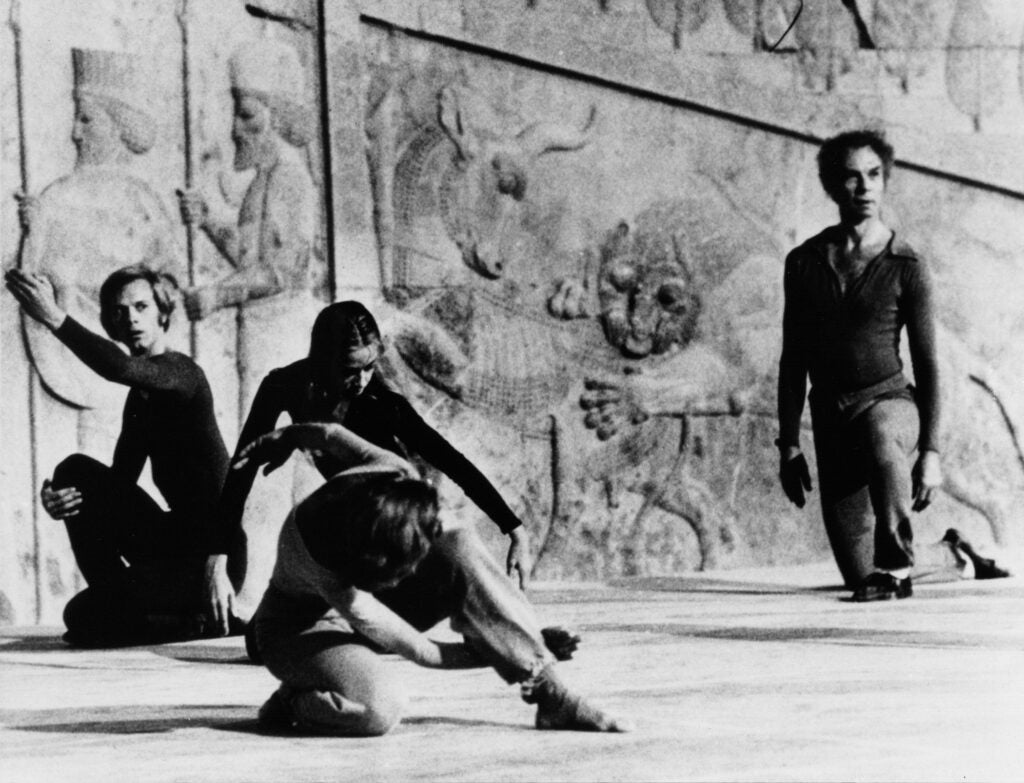

The exhibition features documents, programs, photos, films and posters from the annual Shiraz Arts Festival in Iran that occurred 11 times between 1967 and 1977. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

When the Islamic Revolution rose up against the Iranian monarch Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi in 1978, an important international arts festival in the ancient city of Shiraz was not just canceled: All of its official records going back a decade were sealed or destroyed. The ruling religious leader, Ruhollah Khomeini, issued a fatwa against it.

“It is exactly the kind of fatwa that was declared on Salman Rushdie for his ‘Satanic Verses,’” said Vali Mahlouji, a London-based curator. “The Shiraz-Persepolis Festival of Arts is basically the single most important cultural project that attracted this sort of death sentence.”

Mahlouji pulled together what existing material can be found related to the Festival of Arts to outline its political and aesthetic impact on progressive art movements globally. “The Utopian Stage,” presented by the Philly-based nonprofit Bowerbird, is now on view at the Asian Arts Initiative in Philadelphia.

The exhibition features documents, programs, photos, films and posters from the annual festival that occurred 11 times between 1967 and 1977. The 12th festival, in 1978, was shut down before it started.

The festival was conceived by Empress Farah Pahlavi and run by National Iranian Radio and Television — one of the first projects of the newly created NIRT — as part of the monarchy’s effort to modernize Iran. It brought together traditional performance arts from the Middle East, India and Africa with avant-garde artists from the West.

In a 1969 television interview, Empress Farah explained the festival harkens to Iran’s long history as a place where diverse cultures and races crossed.

“We wanted to continue this tradition of being a meeting between Orient and Occident,” she said. “We wanted the Festival of Art Shiraz to be the melting pot of nations.”

That melting pot can be seen in the striking poster art merging traditional Persian and South Asian cultural graphics with mid-century Western design sensibilities: Think Ravi Shankar meets Saul Bass.

Empress Farah does not appear in the exhibition at AAI. Mahlouji describes the festival as a highly contested space, then and now, both aesthetically and politically. When he started displaying the material 10 years ago, four decades after the festival was canceled, people were still hesitant to talk openly about it.

“People were calling me either a monarchist sympathizer or in Islamist sympathizer, for the same exhibition at the same museum,” he said.

Mahjouli’s project is to investigate what actually happened at the festival during its 10-year run, and how it fit into larger cultural resistance movements, such as Pan-Africanism, the U.S. Civil Rights Movement and the French protests of 1968 that brought much of the country’s economy to a standstill.

“The push that drove the festival was very much linked to the historical moment,” Mahjouli said. “Consider 1960: Seventeen African countries declared independence that one year. Just six years after that, in 1966, we had the First World Festival of Negro Arts, as it was called, in Dakar, Senegal.”

What actually happened?

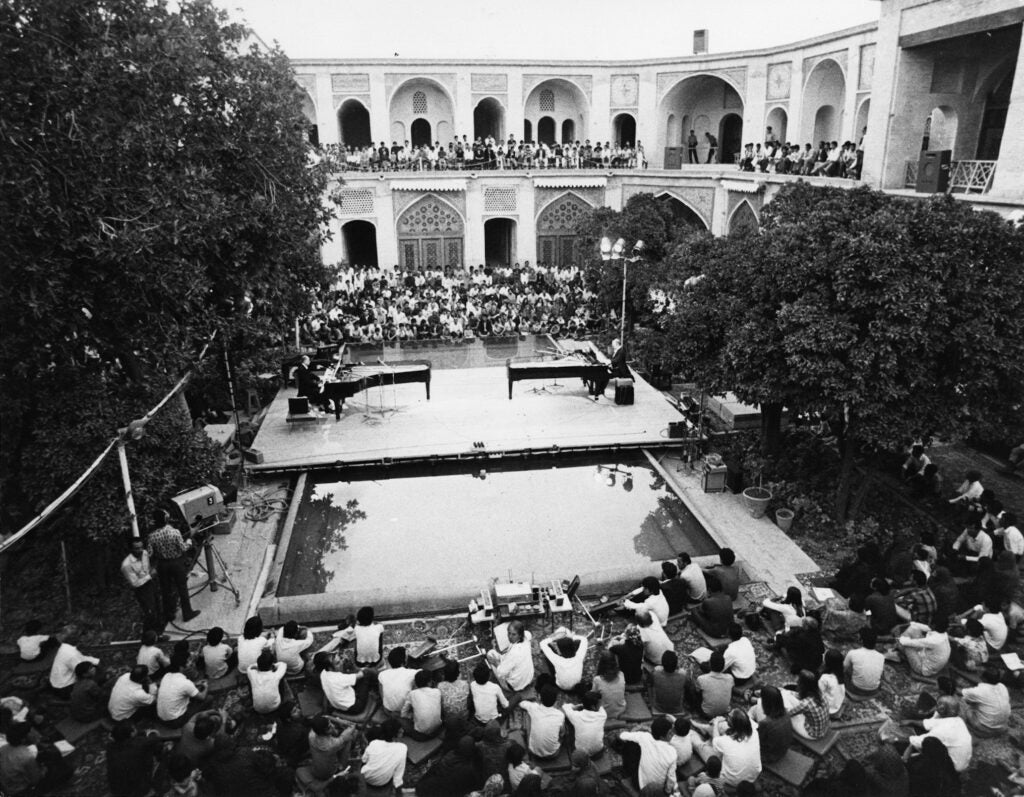

The Shiraz Arts Festival commissioned artists — primarily music and dance, but also some visual artists — to perform in various locations in the Shiraz-Persepolis region, an area known for its traditions of poetry, flowers and wine. Performances were mainly in outdoor public areas.

Organizers intentionally programmed avant-garde performances alongside traditional ones. Audiences could see performances by artists like Ravi Shankar, John Cage, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Merce Cunningham and Jerzy Grotowski.

In 1969, the festival was organized around a theme of percussion, featuring American jazz drummer Max Roach and singer Abbey Lincoln performing alongside Indian percussionists, as well as a gamelan orchestra from Bali, Indonesia.

In 1968, the radical Iranian theater artist Bijan Mofid produced his quasi-musical play “Shahr-e-Ghesseh (City of Tales),” about a community of animals played by actors wearing animal heads, each telling an archetypical fable about power dynamics. “City of Tales” is now considered a seminal play of modern Iranian theater.

After the Islamic Revolution, Mofid went into hiding, eventually fleeing Iran for the United States, where he died shortly after. The exhibition features a short film excerpt from “City of Tales.”

In 1972, the festival invited the American experimental theater artist Robert Wilson to stage his impossibly epic play “KA MOUNTAIN AND GUARDenia TERRACE,” which lasted 168 hours: an entire week of continuous performance on the top of a mountain in Persepolis.

Anticipating the politically fraught conditions the festival operated under, Wilson addressed a press conference in Shiraz wearing a black blindfold, as though expecting a firing squad. According to festival records Mahjouli uncovered, Wilson initially wanted to conclude his marathon performance of “KA MOUNTAIN” by blowing up the top of the mountain, a request that was denied.

Mahjouli said many of the performances leaned into improvisation and devised theater, in part to evade censors who insisted on reviewing scripts beforehand.

“Inherent in the kind of performances that came to this festival was this notion of an emancipatory free will,” he said. “They moved away from text-based theater drama, towards what they called the true, emotional resonating core of drama itself.”

“That sort of stuff is quite transcendental and transcultural,” he said. “It’s not the sort of thing that happens every day.”

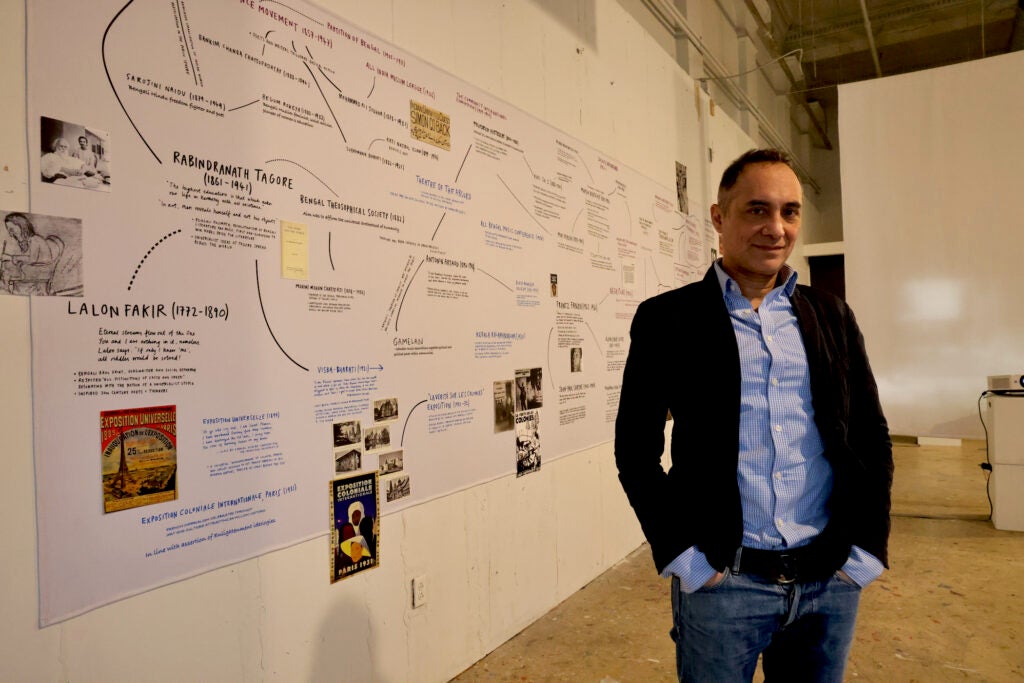

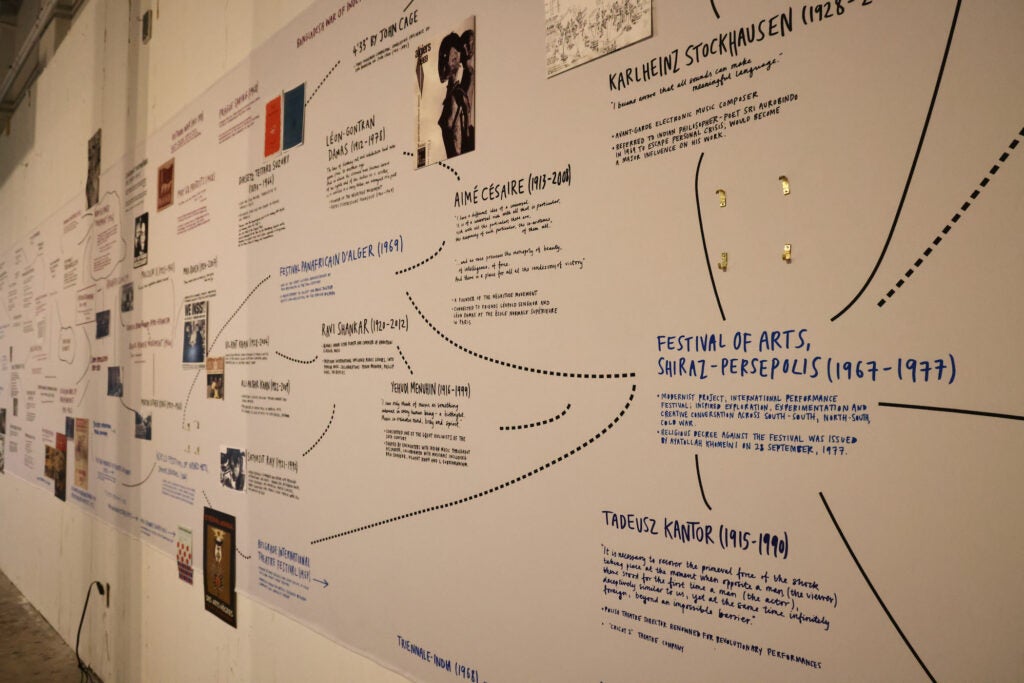

The exhibition at AAI features an enormous flowchart created by Mahjoouli, about 36 feet long, mapping out the philosophical and political interconnections of radical global movements. Using circles and arrows, Mahjouli offers a timeline from the 19th century to the 1980s featuring, for example, Antonin Artaud, Frantz Fanon, Malcolm X, Black Mountain College, Alain Locke, the Situationists, Ramana Maharshi and Shūji Terayama.

Mahjouli arranged his “Histories of Solidarities: A Cultural Atlas” chronologically, left to right, but said the influences of radical art are not linear. He had wanted to draw more arrows showing connections that skipped across time, but that would make the chart graphically incoherent.

“A Utopian Stage“ will be on view at Asian Arts Initiative until March 30.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.