On the Day of the Dead, Philly’s oldest Aztec dance troupe turns 20

On the Day of the Dead, Brujo de la Mancha celebrates two decades of advocating for and celebrating his Indigenous culture.

Listen 1:22

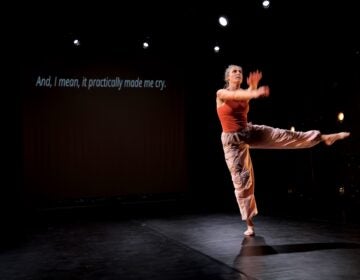

Members of the Aztec dance troop, Ollin Yoliztli Calmecac, rehearse for the troupe's first theater performance, an original play about migrating to the Mexican border. It’s called ''Camine, Camine, Camine Pero Nunca Llege'' (''Walk, Walk, Walk, But Never Arrive''). (Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

On Wednesday, Ollin Yoliztli Calmecac will perform its 20th Day of the Dead celebration.

Philadelphia’s oldest traditional Aztec dance troupe was co-founded by an immigrant from Mexico City in 2003. Brujo de la Mancha said Aztec dancing allows him to connect with his Indigenous heritage.

“We are far away from where we are coming from, and it’s the only thing that allows us to bring who we are,” he said. “It depends, because there is mariachi, there is cumbia, there is norteña, there is ranchera. How you grow up as a Mexican, that’s the thing you think about Mexico.”

The Day of the Dead event at The Rotunda in West Philadelphia will feature dancing, a short documentary made by the Ollin organization, “Y Nosotr@s Que?”, about how Mexican immigrants lived in the city during the COVID-19 pandemic, and an ofrenda — a public Day of the Dead altar.

The event will also launch a new direction for the dance troupe: theater.

A short, original play “Camine, Camine, Camine, Pero Nunca Llege” (“Walk, Walk, Walk, But Never Arrive”), that traces the experience of crossing the border, will be performed. De la Mancha said the story is loosely based on the immigration experiences of the cast members.

Apropos to Day of the Dead, “Camine” is tragic, with a ghost. The performance is mostly physical with some Spanish dialogue and limited phrases in English.

“We do it in Spanish because we want Mexican and other Spanish speakers to come and see it,” he said. “It can be healing to understand the process of letting go and assume that you went through that, but you never have the time to go to the psychiatrist, or something, to let it go.”

De la Mancha crossed the border at Tijuana in 1998 when he was 20 years old. Through chance encounters and the whims of fate, he made his way to Philadelphia, where he had neither friends nor family. While he found a Latino community here, it was largely Puerto Rican.

He said he had a hard time finding Mexican culture, particularly one that resonated with his own Indigenous background: His grandmother grew up in Xico, in the Veracruz mountains, with its mixture of native Maya and Olmec cultures. She did not learn Spanish until later in life when she moved to Mexico City.

Yet another chance encounter changed his life again when he met Daniel Chico Lorenzo, a man from Puebla living in Philadelphia. He asked De la Mancha if he would be interested in Aztec dancing.

“I said: ‘Listen, I’m not Christian. I’m not Catholic, so I’m not going to do the concheros dance, the seashell dance,” De la Mancha said.

The concheros dance is typically associated with the early Spanish colonial period, when the influence of conquistadors altered the traditional Aztec dance.

“I want to do the warrior dance. I want to do my culture,” De la Mancha recalled telling Lorenzo. “He said, ‘I do, too. Let’s talk some more.’”

That was in 2003, when the two launched Ollin Yoliztli Calmecac, in the native Aztec Nahuatl language, which roughly translates to the Institute of Movement in the Blood. De la Mancha discovered he instinctively knew a lot of Aztec dance moves, likely from having watched it performed many times while he was growing up.

But he still had a lot to learn.

Ollin Yoliztli Calmecac became a nonprofit in 2006 and that allowed De la Mancha to raise grant money and bring in master Indigenous folk artists, such as flute player Xavier Quijas Yxayotl and dancer Roberto Franco Totokani.

“For some people it came naturally. Maybe it’s in our blood, in our genes, and by hearing the drum we wake up all the sensory things,” De la Mancha said. “But when the masters came I saw how much more complicated are the steps.”

Since starting the company, he has seen the Mexican population become more visible, and the culture becoming more prominent, even for Mexicans for whom Spanish is not their primary language.

“Twenty years ago it was difficult to tell people to come dance because people were so worried about immigration. People were scared,” he said. “Cultural identity was lost: ‘I don’t know where I am. I don’t know who I am. I come from a small town and I never went to Mexico City to learn Spanish.’ They just come straight here, however they do it.”

De la Mancha knows that fear as an undocumented immigrant himself. He is currently going through the process of obtaining legal status. Despite founding a longstanding cultural nonprofit, his status in the United States had never been secure, particularly during the administration of President Trump.

He had made plans to return to Mexico City, and other plans for Canada, neither of which he could likely return from.

“The reason I was trying to go back to Mexico was because my father died five years ago,” he said. “That’s the only connection I have. I never met my mother.”

He never left Philly.. He said he knows his immigrant audience, because he is one of them.

“For me and the Ollin, we did it all as newcomers, as new Mexicans who came to stay and make new generations of people here,” he said. “We were not sent by the Mexican government. We get no money from the Mexican government. Some of us, we’re still struggling with the immigration process.”

The Ollin Yoliztli Calmecac free community event will be at the Rotunda (4014 Walnut Street) on Wednesday, Nov. 1, from 6 p.m. to 9 p.m. Outside the Rotunda, a traditional ofrenda altar will be set up and accessible at all times until November 8.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.