Next Philly mayor should ‘believe in the possibility of the arts,’ cultural leaders say

Today, the Greater Philadelphia Cultural Alliance is releasing a paper with five recommendations aimed at the 10 mayoral candidates.

Listen 4:01

File photo: Looking east toward City Hall from Eakins Oval. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

This story is a part of the Every Voice, Every Vote series.

What questions do you have about the 2023 elections? What major issues do you want candidates to address? Let us know.

Leaders of Philadelphia’s arts organizations want the next mayor to create a dedicated fund for the arts, and elevate the Office of Arts, Culture, and the Creative Economy into a cabinet-level department.

Today, the Greater Philadelphia Cultural Alliance is releasing a paper with five recommendations aimed at the 10 mayoral candidates. At the top of the list: a steady funding stream for the arts sector, and a new deputy mayor able to integrate arts across all city departments.

“We want an integrated arts plan,” said GPCA president and CEO Patricia Wilson Aden. “We want to see arts and culture not siloed within an office, but integrated into commerce, integrated into public safety, integrated into families and children’s departments throughout the mayoral administration.”

The GPCA outlines other recommendations, including the development of a plan to leverage arts for economic recovery, prioritize programs that recognize the city’s creative assets, and showcase the artistic and cultural life in Philadelphia, particularly as the nation’s 250th birthday approaches in 2026.

Jane Golden, director of Mural Arts Philadelphia, had a similar list of demands. She was asked to offer her thoughts at a recent gathering of mayoral candidates at the Barnes Foundation. She told them she wants City Hall to adopt a Bill of Rights for artists.

“There are a lot of artists in the city doing really wonderful work who feel disconnected. They have questions. They’re looking for support. They don’t know where to turn. They come to Mural Arts,” Golden said. “I feel in some way we’re like a shadow Office of Arts and Culture, because people come to us with questions ranging from taxes to live-workspace to unemployment to health care.”

Part of the solution

In the 1990s, former Mayor Ed Rendell had a vision for the arts as an economic engine in Center City, a vision that included building the Kimmel Center. Now, 22 years later, its CEO Matías Tarnopolsky wants to see the next mayor prioritize arts education in schools.

“I am blown away by what Philadelphia arts organizations do in the realm of education and community,” he said. “But it’s got to be part of the educational system. That’s where the city can really help.”

Last week, Tarnopolsky hosted a mayoral forum that asked candidates for their vision of the city’s arts sector. Like many arts leaders, Tarnopolsky says funding the arts is not diverting taxpayer money away from urgent public safety and social issues in Philadelphia — such as crime, education, and poverty — but rather supporting those efforts. Arts organizations can be part of the solutions to city problems.

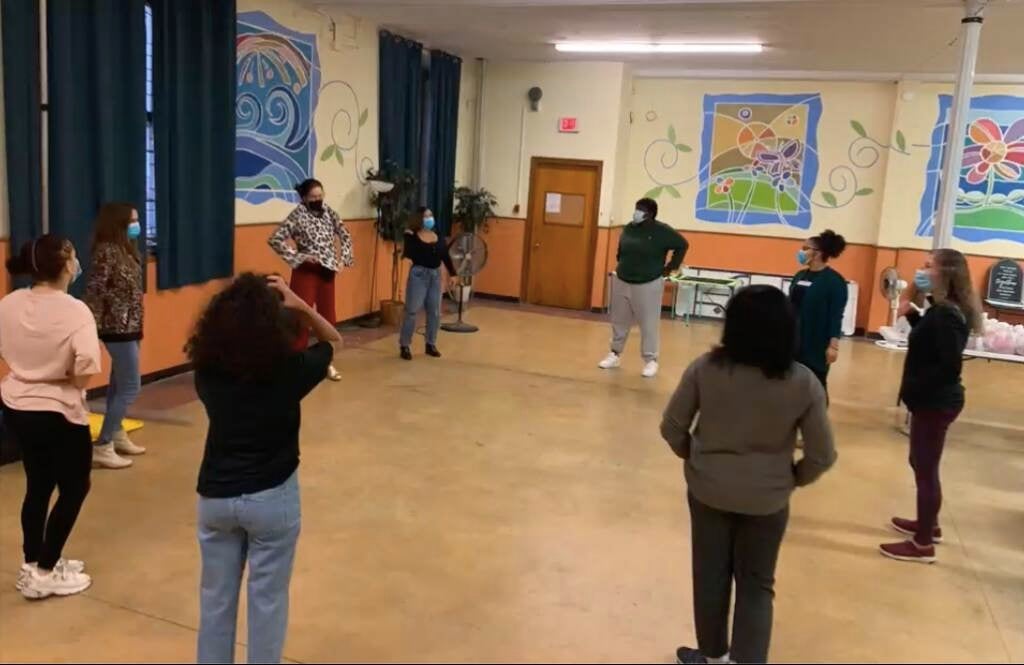

Take for example Power Street Theatre, a small theater company based around the Kensington and Fairhill neighborhoods of North Philadelphia, often making work oriented around the Latino community.

Along with staging new plays, Power Street also offers adult theater classes, such as Land and Body, a series of classes helping people write monologues which are ultimately performed by professional actors.

Playwright and director Erlina Ortiz said the classes are designed to welcome adults with no previous experience in theater.

“There are more opportunities for young people to get access to the arts. We encourage a lot of young people, like: ‘You can be whatever you want! Try this!’ ” said Ortiz, the incoming general manager of Power Street. “But once we hit 19 or 20, it’s, like, ‘OK, you chose what your dream is. If you haven’t done it yet, you’re done.’”

For the most recent Land and Body class, participating adults were asked to select a current news article related to their neighborhood. Using the article as a prompt, they invented fictional characters grappling with topical issues.

The writers chose heavy topics — such as last year’s fatal shooting of high school football players in Roxborough — as well as lighter fare, like a meditation on immigration written from the perspective of a raccoon relaxing in someone’s backyard. They then shared their character monologues with the group, which offered feedback.

The writers invented characters outside of themselves, empathized with them, and figured out what they might say. Ortiz recalled encouraging one of the writers to use the news story about the Roxborough shooting to create a character starting to recognize her own racial bias.

“Why don’t you write from the perspective of somebody you don’t agree with, or someone that you’re trying to understand?’ That kind of scared her,” Ortiz said. “She’, like, ‘I don’t know how to get into the head of someone who feels and thinks this way.’”

Another participant in the class, Anthony Webb, said he stuck out among his classmates as a somewhat older, Black man from Germantown in a room full of relatively young, mostly Latino people from North Philly. Webb said it did not take long to find common ground with his classmates.

“We’re all suffering from the same thing. We’re trying to escape, or develop something new, and there are forces that are waging against that,” he said. “You come to class with a set thought of how people are and how the world is. But you come out of the class with a different appreciation for the world.”

Ortiz says the main takeaway from the class is not a finished script, but the experience of building community through creative work, something adults are often lacking.

“I think that’s a really big part of what leaves people in these very dark, low places,” Ortiz said. “Seeing where we are as a society right now, where people have lost their sense of empathy or their sense of being able to connect with people. That’s one thing theater does especially well.”

Golden said arts programs, like Power Street and her own Mural Arts with its community programs such Restorative Justice, can make people into better citizens.

“We need leadership to believe in the possibility of the arts,” she said. “It’s not just a possibility: It happens. We could pull names out of a hat of 20 organizations in the city and look at what they’re doing up close, and be deeply moved by the power of what they’re doing.”

Inconsistent arts policy

Support for the arts sector from City Hall has traditionally been subjected to the will of the mayor, and different administrations have treated the arts sector inconsistently. The Office of Arts and Culture was established in 1986 by then Mayor Wilson Goode. The subsequent mayor, Rendell, established the Culture Fund, an independent nonprofit funded by the city budget that distributes money as arts grants.

The next mayor, John Street, closed the Office of Arts and Culture. Then Mayor Michael Nutter reopened and renamed it as the Office of Arts, Culture, and the Creative Economy. Under the next mayor, Jim Kenney, the office was shrunk and moved inside the office of the city’s Managing Director.

Money in the annual city budget for the Cultural Fund can fluctuate wildly from year to year. In the pandemic budget of 2020, Kenney proposed to zero out the Cultural Fund entirely, but through negotiations it was somewhat restored. Then, last December the arts sector got an unexpected $21.3 million windfall during the city’s mid-year budget transfer.

“The Office of Arts, Culture, and the Creative Economy is empowered only to the extent of the vision or the will of the mayor,” explained Aden. “It’s been moved around. The budget has fluctuated. We believe that a department will stabilize investment in the arts.”

Golden, who founded Mural Arts 37 years ago and led it through five mayoral administrations, said she is wary of politicians giving lip service to the arts by praising the city’s cultural life without backing it up with investment. She and other arts leaders are demanding that the arts become a permanent department of City Hall, which may involve a change in the city’s charter.

“City government is very hierarchical. If you’re lower on the food chain, you’re lower on the food chain. The closer you are to power, the closer you are to power,” Golden said. “In order to be successful, you have to have access to the mayor. You need the mayor to use their bully pulpit on behalf of the arts.”

The city’s arts sector is looking ahead to the next administration’s term, which will include the year 2026, a potentially pivotal year in the life of the city when both the World Cup soccer games will come to Philadelphia, as well as the 250th anniversary celebration of the United States.

The world will be watching.

“As we look towards 2026, being that champion that says, ‘Philadelphia is a world-class destination because of our very distinctive arts and cultural offering,’ having a mayor out front saying that is powerful,” said Aden. “We would love to have that sort of champion, that bold leadership in the next mayor, as well as someone who backs that up by making investments.”

This story is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Lead support is provided by the William Penn Foundation with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute, Peter and Judy Leone, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Harriet and Larry Weiss, and the Wyncote Foundation, among others. Learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters here.

This story is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Lead support is provided by the William Penn Foundation with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute, Peter and Judy Leone, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Harriet and Larry Weiss, and the Wyncote Foundation, among others. Learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters here.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.