2 South African artists converse across the apartheid timeline at the Barnes

The Barnes Foundation hosts work by two artists: one making work since apartheid, the other growing up in post-apartheid South Africa.

Lebohang Kganye looks at her patchwork cloth re-creation of a black and white photo of her great-grandmother. (Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

Johannesburg artist Lebohang Kganye started researching her family history after her mother died in 2010, and discovered her surname has been spelled at least four different ways.

The forces of apartheid had split up her relatives and pushed them into sometimes unwanted migration, scattering to outlying parts of South Africa. Men often left their families to find work, sometimes never returning. It warped the spelling of Kganye.

“We have eleven official languages in the country, so there’s a particular way in which it’s spelt according to that language,” Kganye said. “Sometimes they would have to identify as a certain tribe for safety reasons.”

The alternative spellings made hunting through official records difficult. Kganye relied on her grandmother’s guidance to locate relatives, from whom she gathered stories about her family. Those stories have become photography collages, performative videos, and a life-size immersive diorama made from cardboard cut-outs. They are as playful as they are revealing about family structures in post-apartheid South Africa.

To Kganye, family memory is intertwined with imagination.

“I really started to think about the family photo album as a kind of performance, and also as a children’s storybook – a place where they could get into character,” she said. “A family photo album is almost constructed as a story, but it’s not a documentation of everyday life. It also becomes, to a large degree, a tool of resistance.”

Kganye’s work is one-half of “Tell Me What You Remember,” an exhibition at the Barnes Foundation pairing the work of an older artist who was making work in apartheid South Africa, Sue Williamson, with a younger artist, Kganye, born in 1990, who grew up in post-apartheid.

The Barnes’ temporary exhibition space is bifurcated:

Turn left into a gallery of Williamson’s work, 10 pieces including “A Tale of Two Cradocks” (1994) which alternates pages describing the life of Matthew Goniwe, an anti-apartheid activist who was murdered by state police in 1985, with pages from an official tourist guidebook for the city of Cradock which makes no mention of the neighborhood where Goniwe lived.

One wall is installed with glass etchings of street maps of Cape Town’s District Six, and re-creations of retail signage from that urban neighborhood from which 60,000 people were forcibly removed in the 1970s after the government declared the region a “white district.” Much of the district was completely eradicated through demolition.

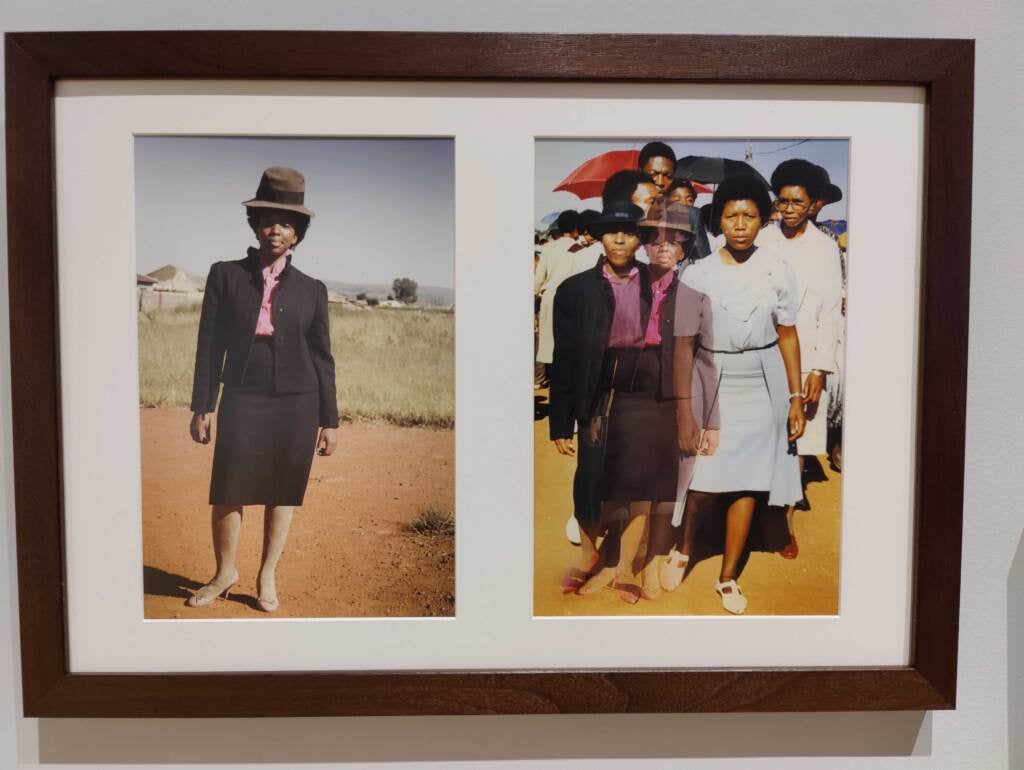

Turn right into a gallery of nine pieces by Kganye, including larger-than-life re-creations of family snapshots of her family matriarchs, rendered in black and white patchwork cloth; and a series of snapshots of her mother in which Kganye, wearing the same clothes as her mother, inserts herself as a ghostly doppelganger.

Together, Williamson’s and Kganye’s work are two perspectives on the disruption of memory due to apartheid.

“So often the older people in the family have been traumatized through something and then they don’t want to share it with the younger generation because they want to protect them,” said Williamson. “They don’t want to talk about it, so it gets forgotten. But it’s so important that young people know their own family history and really understand what the entire family has gone through.”

“Tell Me What You Remember” was curated by Emma Lewis, now a curator at Turner Contemporary in Margate, England. The Barnes exhibition is its premiere. It’s also the first time each artist, Williamson and Kganye, have had large exhibitions of their work in the United States.

Both are recognized artists in South Africa who have had their work shown around the world, but before this show they never knew each other personally.

Born in 1941 in England, Williamson’s family moved to South Africa when she was a child. In the 1960s, she worked as a journalist before moving into fine art, and in the 1980s was part of a movement of South African artists committed to use their work to fight apartheid. Some of her work draws from the 1996 Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the gap between official state memory and personal memory.

As a former journalist, Williamson says much of her work comes out of talking to people.

“The language that people use, the quirky language, I didn’t want to change it,” she said. “I like the actual words people use. I do think that people’s stories and exactly what they say – we need to listen to. Not try to smooth it out, tidy it up.”

Kganye also uses spoken language in her work, as in the video piece “Dipina tsa Kganya,” but the voice is barely audible.

“Dipina tsa Kganya” is a three-channel video projection wherein Kganye dressed in a period dress — what appears to be a 19th century gown — tending to antique machines that metaphorically represent aspects of her family legacy. Heard in the installation’s soundtrack is an excerpt from one of her recordings of her family’s direto, a Sesotho word for a traditional praise poem.

Many surnames in Africa have an associated praise poem, a familial oral tradition. As part of her research into her own family, Kganye recorded relatives singing their family praise poem.

“I became more interested in this praise poem, but also because it only documents the male side of the family,” Kganye said. “The work is about bringing in the voices of my grandmothers who, to a large degree, they’re the people that were telling me about this history of the family.”

For most viewers inside the video installation gallery, the recording is undecipherable: not only is it mixed very quietly into the soundtrack, it’s recited in Sesotho, one of the 11 languages of South Africa. The voice is not meant to be understood, rather to evoke family like a kind of audio talisman..

“Tell Me What You Remember” will be on display at the Barnes Foundation until May 21.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.