PAFA invites women to take up space in new feminist exhibition

The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts has reopened in a big way, with big art on big walls that take your breath away with their sheer size.

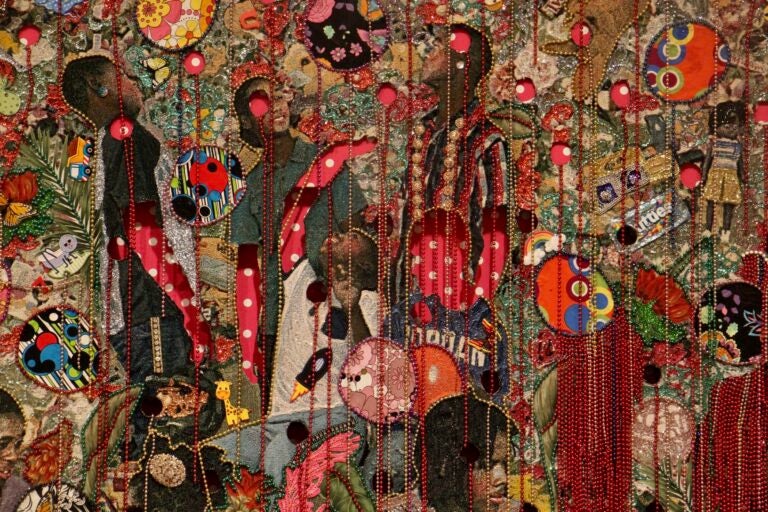

A closer look at Ebony G. Patterson's monumental mixed media work reveals complexity and detail. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

It’s been almost a year since museums and art galleries shut their doors for the coronavirus pandemic, opening sporadically only to be abruptly shut down again as infection rates rise and fall. Many are now reopening, trying to pick up where they left off last March, some adding new exhibitions to welcome back the art-starved who have been forced to make do with glimpses of paintings peeked at through online portals.

The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts has reopened in a big way, with big art on big walls that take your breath away with their sheer size.

“It’s nice to let the work overwhelm you,” said Brittany Webb, curator of 20th-century art at PAFA. “It overwhelmed us, even when working on it. We had to step back and say, ‘Phew, OK!’ It’s one thing to think about an artwork in your head, it’s another thing to stand in a gallery and look up at a piece.”

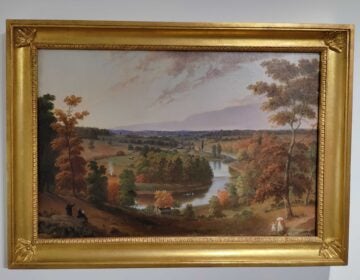

“Taking Space: Contemporary Women Artists and the Politics of Scale” features monumental-sized installation art in the PAFA’s Samuel M.V. Hamilton Building, originally built as an automobile showroom with high ceilings and a floor plan spacious enough for a Hudson to make a U-turn. The huge installation by Ebony G. Patterson “…doing what they always do…(…when they grow up…)” (2016) is floor-to-ceiling pink wallpaper with white polka dots, hung with two large woven tapestries thickly festooned with beads, plastic toys, and candy wrappers.

The whole piece is about 30 feet wide and 20 feet tall. A visitor has to stand against the opposite wall to be able to take it all in, but to investigate the work the viewer must stand close, about three feet away. You have to physically move to understand the piece, something not possible in a virtual art gallery.

Woven into “…doing what they always do…” are images of Black children. The way Patterson clusters the children with toys suggests innocent play, while holes in the tapestry suggest ruptures in that childhood. The artist has said the killings of Black teenagers like Trayvon Martin and Mike Brown influenced her work.

The whole piece is densely packed with material, color, and meaning. Patterson clearly intended for you to lean in.

“I think that gets to the heart of something that Ebony G. Patterson wants us to do with that piece, which is to look past what we know about something, what we see in the media about African American children,” said co-curator Jodi Throckmorton. “You look past all these beads and decorative things to look at images of innocent children.”

“Taking Space” features more than 60 paintings, drawings, sculpture, and installation works, many very large and all by women. Some pieces are self-portraits: Joan Brown sarcastically painted herself dressed in a spotless sundress while working in her paint-splattered studio; Mickalene Thomas’ “Din Avec la Main Dans le Miroir” is a huge mashup of clashing patterns and glittering rhinestones.

Other artists represent themselves without portraying themselves. Sculptor Brie Ruais begins with a pile of clay equal to her own body weight – 130 pounds – and beats, scrapes, and mashes it as far as her arm span can reach. She only stops working when she is physically exhausted. The resulting “Scraped Away From Center, 130 lbs (Night)” is a fired and glazed document of Ruais’ fight with clay, a circle defined by her own body with evidence of her fists molded into the shape.

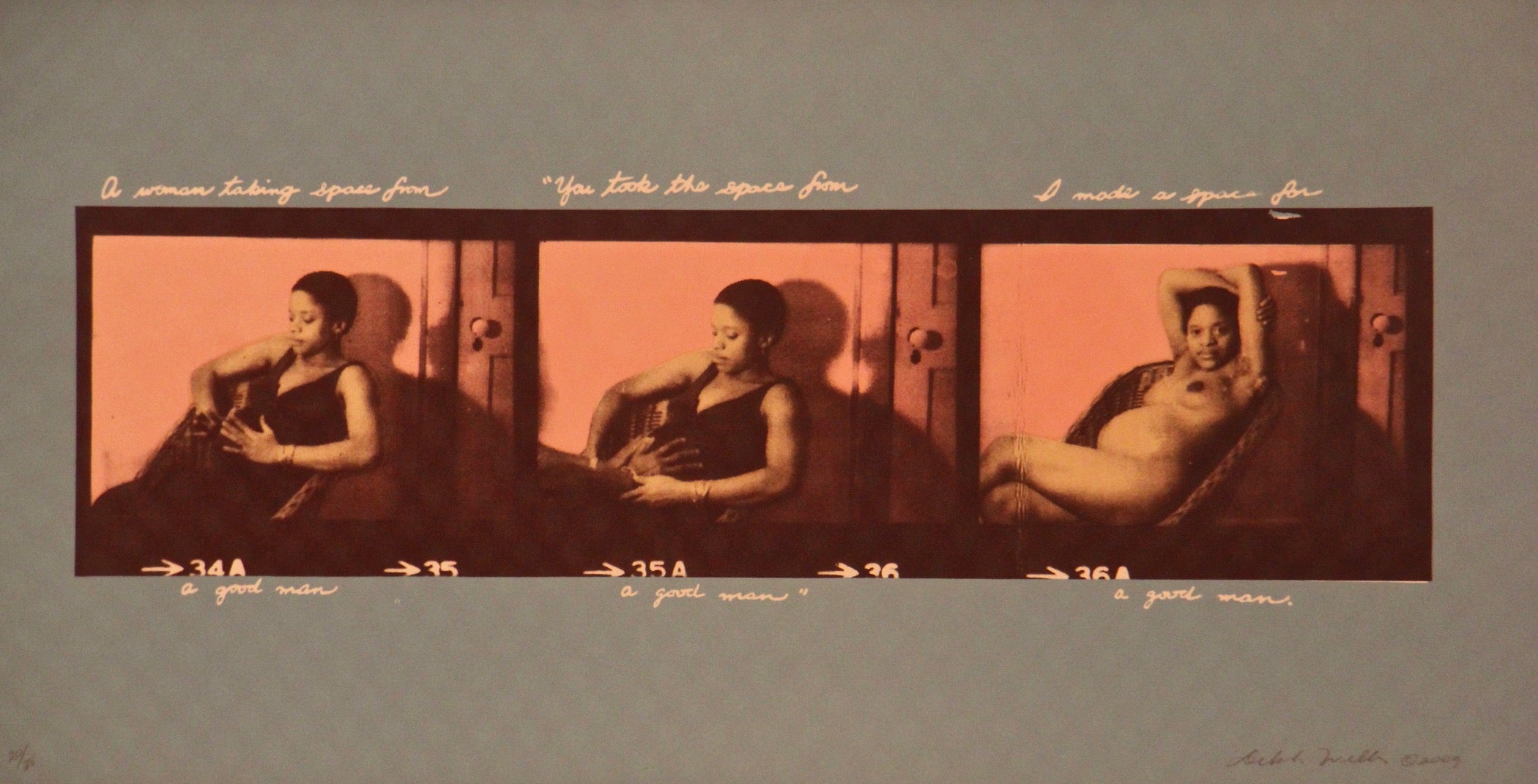

The exhibition’s “Politics of Scale” subtitle is not just about physical size, but space that women – in this case women artists in particular – take in culture. The name of the show comes from Deborah Willis’ self-portrait triptych “I Made Space for a Good Man,” showing herself in three stages of pregnancy with her son.

In terms of square inches, “I Made Space” is one of the smallest pieces in the show, but looms large in the exhibition’s message.

The piece is a response to an insult the Philadelphia-born artist received in the 1970s as an undergraduate at the Philadelphia College of the Arts (now the University of the Arts). A professor said he regretted Willis was in his class taking up the space which could otherwise have been given to a more promising male artist.

“We were really struck by the idea of cutting off a young woman’s ability to dream,” said Webb, adding that the professor at the time did not see Willis having much of a career as an artist. “There are so many ways she went on to have a life that proves that wrong.”

Not only did Willis go on to have a prolific and successful career – she was named a MacArthur “genius” Fellow in 2000 – but also the pregnancy she displayed in “I Made Space for a Good Man” resulted in Hank Willis Thomas, a widely celebrated conceptual artist.

“This show is exactly up my alley. These are the things I think about,” said Clarity Haynes, another artist in the show who studied locally at both Temple University and at PAFA. She now lives and works in upstate New York.

“The body can be the site of a lot of social and political violence – sometimes literally and sometimes it’s more figurative violence in which you are being told how you naturally are is not OK,” she said.

Haynes’ portrait in the show, “Janie” (2014), is the naked torso of a fat woman from her neck to her waist. The model’s face is not shown, rather the picture celebrates her abundant flesh. The portrait is part of Haynes’ decadeslong, ongoing project of painting naked torsos.

“Janie” is Janie Martinez, who sat for Haynes as she painted the portrait from life over the course of a year. Haynes and Martinez become close friends. The artist asked the model to write something during the process:

I was here.

I was alive.

I took up space.

I was somebody.

At the time of the writing, Martinez was not yet sick with cancer. She was later diagnosed and died in 2019.

“Janie was an incredible person with a huge influence,” said Haynes. “She was an actress and activist who was well-known in the New York theater community.”

Haynes painted Martinez larger than life, filling the canvas edge-to-edge, to take up more space. Like all of her recent paintings in the torso series, Martinez’s image is meant to be formidable.

“Janie was a fat activist,” said Haynes. “Embodiment is really important for social empowerment. If you don’t feel comfortable in your body, or like you deserve to walk through the world, you’re not going to feel comfortable doing a whole variety of things in the world.”

All of the 60 artworks in “Taking Space” are from PAFA’s collection. Webb said a majority of them – 35 or 40 – were acquired in just the last five years. The exhibition shows off PAFA’s collecting prowess in collecting and curating art by women.

“I think it’s an amazing example of feminist curating,” said Haynes. “PAFA is just exploding with cutting-edge feminist curating and collecting. I’m really excited about it, especially as a former PAFA student.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.