New friends, missing students, and lingering tests: Inside a reopened North Philly school

A North Philadelphia school tries to welcome students back, sort through confusion, and steady itself for an unprecedented year.

Listen 4:43

E.W. Rhodes 6th grade students London Wesley (left) and Saminh Wheeler (right) are new friends who bonded over their love of cats. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

It was the kind of small interaction only a hawk-eyed educator could see and diagnose.

In the back corner of an eighth-grade math class at E.W. Rhodes School in North Philadelphia, two boys whispered back and forth.

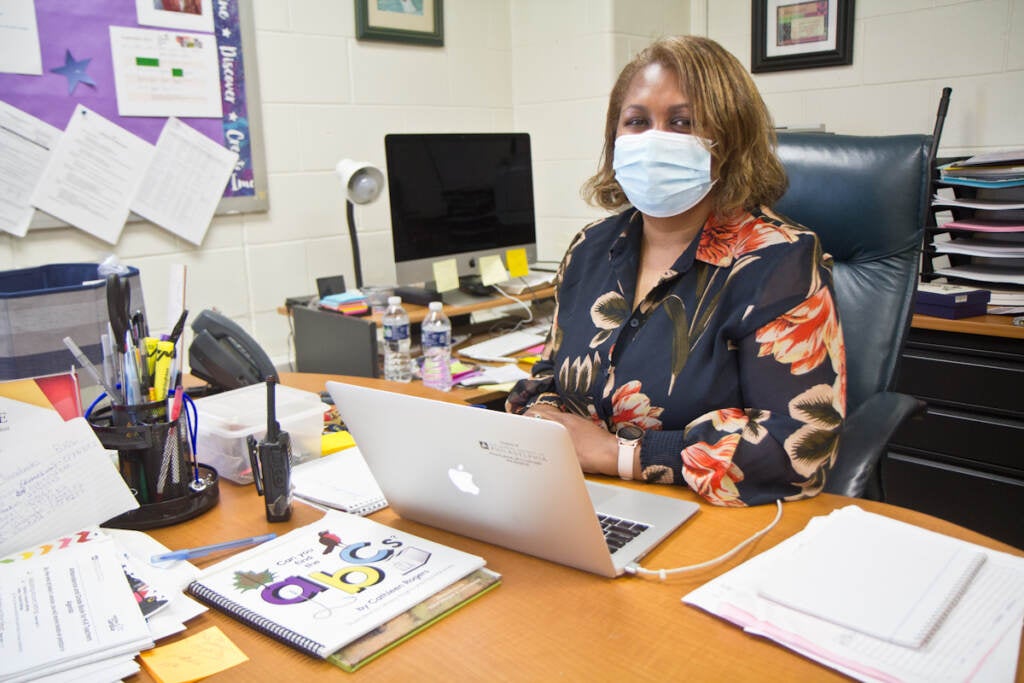

It looked like a playful exchange. But Principal Andrea Surratt — standing in the opposite corner — sensed a joke was being made at one of the boys’ expense.

“Leave his hair alone,” Surratt said in a firm voice, just loud enough to reach the other side of the room.

One of the boys was waiting to get cornrows, but his hair, for the moment, hadn’t been styled. It was hard to miss on the second day of school, among the rows of crisp outfits and haircuts.

“He looks like Einstein,” exclaimed his classmate.

Surratt raised her voice louder, as if to end the conversation.

“I like it.”

Surratt had her eye on the boy. He’d barely logged on last school year, when his seventh-grade classes were completely virtual. His mom worked long hours, Surratt later explained. She was tough to reach.

One day earlier, on the first day of school, the boy and his younger sibling showed up — uniforms on and eager to learn. She couldn’t explain this sudden reversal, but she wanted to keep it that way.

“They’re here,” said Surratt. “That’s the blessing. They’re here.”

Last year, there were about 20 children in this school of 500 that Surratt and her staff could never quite track down. Now some are trickling back as the School District of Philadelphia offers full-day, full-week classes for the first time in 18 months. Students who logged on faithfully during that time are re-acclimating, too.

As this unusual school year begins, the Rhodes staff spent the first week of school affirming and reaffirming a simple message:

“We’re family,” said Surratt.

Surratt is working amid a moment of urgency in American classrooms, with needs extending in so many directions it can feel overwhelming.

Studies show students fell behind academically during the pandemic — especially students at high-poverty schools like Rhodes. Students suffered emotional distress brought on by isolation. Students missed opportunities to build social skills.

Amid all that upheaval — and with the specter of COVID disruptions still looming — where should schools start? What do they tackle first?

WHYY spent time at Rhodes to capture scenes from the first days of an unusual, and unusually important, school year.

Who’s here?

Every morning it seemed a carousel of parents cycled through the front office — each one with a child or two in tow.

Surratt, ever the diplomat, greeted them as she shuffled between her office and the next appointment.

How are you?!

You ready to start?

And he’s in uniform. Excellent!

A new school year always brings a bit of confusion. Some families show up unexpectedly. Some enrolled students never appear.

But this year felt more unsettled to Surratt. On the first day of school, 77% of the students on her rolls attended classes. Typically, that number would be about 10% higher, Surratt said.

Before the school year could shift into high gear, the Rhodes team needed to know who was actually supposed to be there.

“That means I need to reach out to these parents to find out where these kids are,” she explained. “That’s the goal for this week.”

As Surratt’s staff made those calls, they discovered that many families had moved — often out of Philadelphia.

One mom told WHYY that her family had been living in North Carolina for a year, but while school was virtual she’d kept her daughter at Rhodes. Another mom had moved with her son to a small city near Nashville, Tennessee in June. It was for “personal reasons,” she said.

Surratt noticed a lot of families moving South, where the cost of living was cheaper. Others told her they simply had to get out of Philadelphia — away from the explosion in gun violence.

In April, a recent Rhodes grad was gunned down about five blocks from the school.

“This year it’s like a mass exodus from Philadelphia,” said Surratt. “They’re going all over the place.”

By the second week of the school year, Surratt’s team had essentially reconciled their rolls.

Some students trickled in after Labor Day. A few families were still wary of sending their children to school in-person, but hadn’t enrolled their kids in the district’s separate virtual school.

“We’re basically caught up right now as far as who’s here, who’s not here,” Surratt said.

Would you rather?

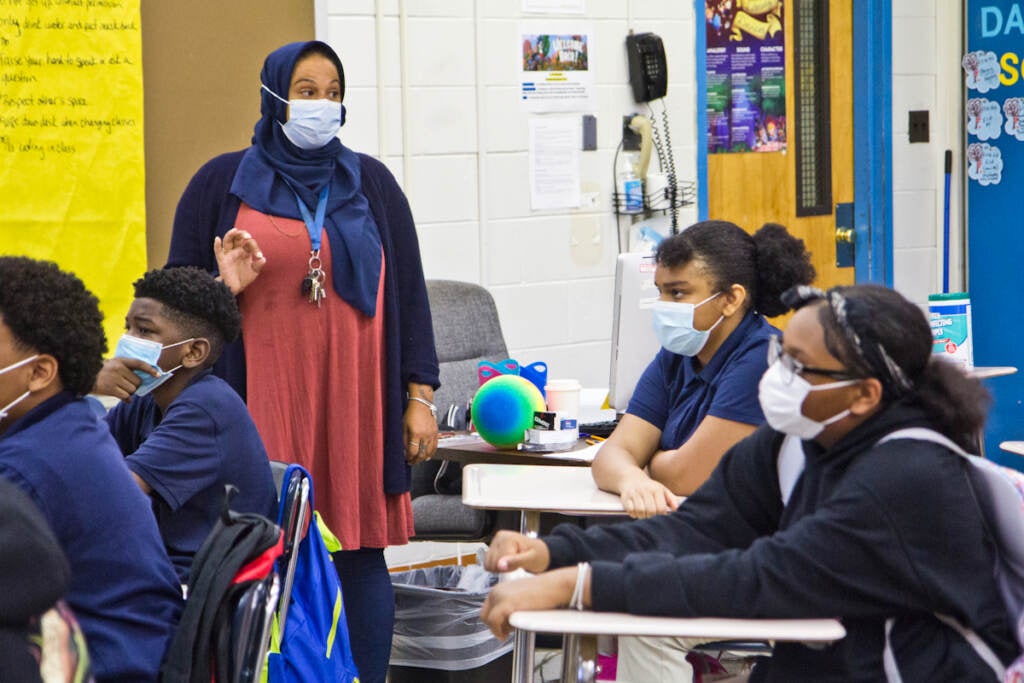

Eighth-grade teacher Nicole Buskey began each day with some music. Just a few minutes to set the mood as students filed in.

By the second week of the school year she’d cycled through Al Green, Dru Hill, and the latest Drake album.

“[To] show them I’m not really old, old,” explained Buskey. “I still get down a bit.”

All of the teachers began each day with a morning meeting, reading from a series of ice-breaker questions provided by the school district.

Would you rather have a pet ant or a pet mouse?

Would you rather never be able to listen to music again or never be able to watch television?

Describe your perfect day…

Buskey began her second day of class with a game where students passed a ball around the room and said the name of the classmate to whom they were passing it. She reminded them several times to speak up as they quickly shuttled the ball around the room.

By the second week, the energy felt higher as the students played a version of “I Spy.”

Buskey had plenty to do as an English Language Arts teacher. Internal assessments showed the school’s reading scores had dipped during the pandemic, according to Surratt. Making up that ground was the school’s primary academic goal.

But for Buskey, Surratt, and much of the staff, there was another goal that came before all of that: establishing relationships with their students.

“My goal is to let students know it’s ok. This is a safe space. You have someone you can trust,” said Buskey.

The ‘honeymoon period’

School days began early.

About an hour before Rhodes officially opened its doors at 8:15 a.m., Surratt noticed a handful of students gathered around the entrance. Each day, she’d let them into the cafeteria where they’d linger under adult supervision.

She wanted to somehow turn these early drop offs into an opportunity. Within the month she expected to christen a “before-school program” where students would get some sort of academic “touch” while they waited for breakfast to begin.

“We have to get books in their hands,” said Surratt. “We have to get them acclimated to reading again.”

The early arrivals personified one of the school year’s pleasant surprises. A healthy chunk of the students seemed energized. They were happy just to be there.

“I can’t explain it,” said one eighth-grade boy. “It’s just been a good couple days,”

“I get to see some of my friends and learn new stuff,” explained a sixth-grade girl.

Khalil Shepherd, the school’s social worker, expected the first week of school to bring friction.

“I thought we’d see a few fights — a lot of non-compliance, a lot of kids eloping from the classroom,” he said.

Instead, he’d seen none of that. He works with about two dozen kids through a behavioral health program called STEP. So far, he hadn’t gotten any “phone calls” about any of them — meaning no major outbursts or disruptions of note.

Shepherd also oversees a program where school safety officers meet for an hour each week with a group of middle school boys. Most land there because a teacher or parent feels they need some extra male guidance.

Last year, done virtually, the program withered to about nine or ten regular students.

This year, about 25 had already signed up, and the first session wasn’t until October.

“Maybe this is just a honeymoon period,” Shepherd said with a laugh.

Waiting for the tests

From an academic perspective, the honeymoon ended quickly.

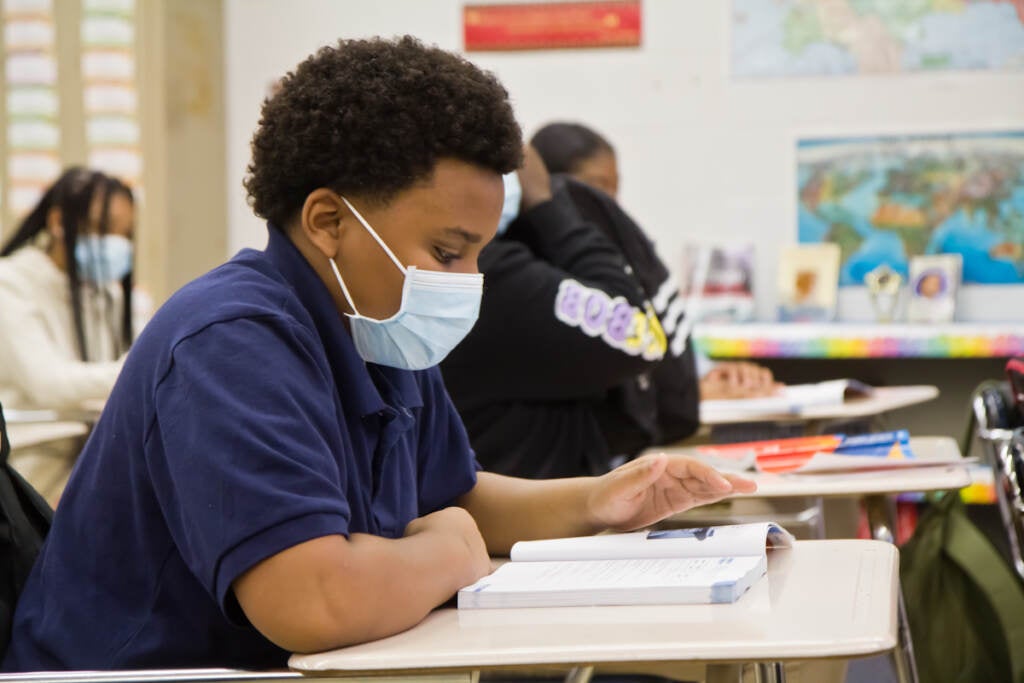

By the fourth day of classes, the school began to administer standardized tests to judge how much the students knew and where they were struggling most.

As they waited for those results, teachers pressed forward with their lessons. And observers monitored.

Two teacher coaches — one from the school and another from the district — circulated through a morning math class. The central office coach mentioned to Surratt that the teacher’s lesson plan felt incomplete.

She said afterward that she wasn’t too concerned right now, as long as the teacher was developing a good rapport with her class. And she was, if the enthusiastic response to the morning meeting was any indication.

“Sometimes our priorities don’t match,” Surratt said with a shrug.

In a first-grade class, students reviewed the letters and their sounds, belting out the vowels in unison. A group of sixth graders read a passage about childhood fears and explained what they learned.

They broke off into groups.

In the far corner of the room, a pair of smiling girls worked together. Both had attended different schools in North Philadelphia last year, but recently moved to the neighborhood near Rhodes.

Despite knowing each other for only a week, they’d bonded quickly over a shared love of cats and the color blue.

“She introduced herself. I introduced myself. And we became best friends,” explained one of the girls.

For new kids at a new school, the semester was off to a perfect start. Asked what they hoped for the rest of the year, one of the sixth-graders put it succinctly:

“No drama.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.