‘This constant wheel’: Philly educators fight to bring truant students back into the fold

In a disconnected world, principals find themselves fighting harder to keep their tenuous ties to families on the fringe.

Listen 4:32

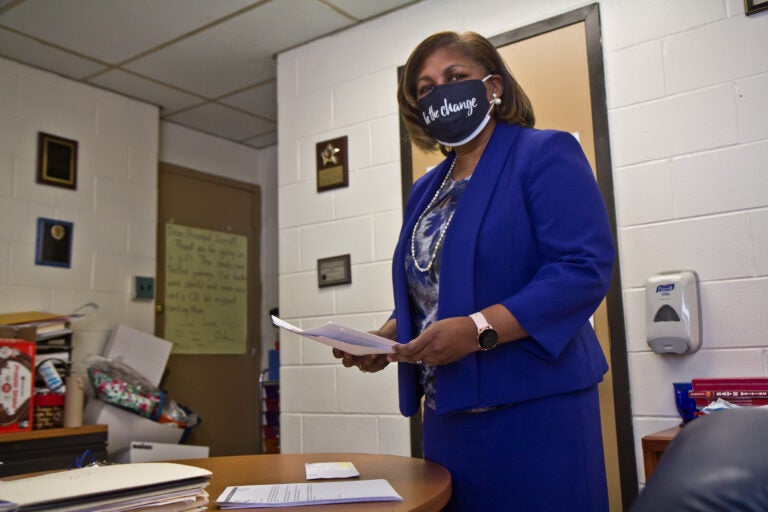

Principal Andrea Surratt at work in her office at E. W. Rhodes Elementary School in Philadelphia. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

About a month ago, a pair of sibling fifth-graders stopped showing up to virtual classes at E.W. Rhodes Elementary in North Philadelphia.

When she got word, principal Andrea Surratt sent the school’s climate manager to the family’s home.

“He said the house was filthy,” Surratt said. “The kids were alone.”

The veteran principal called their mother, but found the phone line disconnected.

Surratt then tracked down an aunt, but she didn’t have a current number for her sister. The aunt thought her nephew might.

So on a recent Friday, Surratt prepared to go down another rabbit hole, her fingers crossed.

Maybe the nephew would have an answer.

“It’s just this constant wheel,” said Surratt, whose school serves students in grades K-8. “You’re constantly battling to get these kids online.”

Surratt told the tale with a tinge of resignation. None of this was surprising to her — just one example of the fight to educate two students in a school of 500.

“We know we’re probably not gonna get the results we want at times,” said Surratt. “But we call every single day.”

Mid-March will mark one year since Philadelphia closed its public school buildings due to the coronavirus outbreak. Since then, none of the district’s 120,000 students have stepped foot in a classroom.

More than 20% of the district’s students have been truant this year, meaning they have more than 10 unexcused absences. That’s roughly 30,000 children.

Truancy is not a new phenomenon in the School District of Philadelphia. But in a disconnected world, principals find themselves fighting harder to keep their tenuous ties to families on the fringe.

It can seem like a Sisyphean task. But at times, it feels like the only task that matters.

“This year everyone has to make a stronger and larger commitment — and be very crafty,” said Laurena Tolson, principal of Add B. Anderson School in West Philadelphia. “That’s one of my new words for the pandemic: crafty.”

‘Boots on the ground’

Tolson’s approach is expansive and exhaustive.

Every school communication goes out three ways: via phone call, via U.S. mail, and through a classroom management app called Class Dojo.

“Every other week I’m ordering about a thousand stamps,” said Tolson.

Each unexcused absence triggers a phone-call home. Not a robo call — an actual call from an educator.

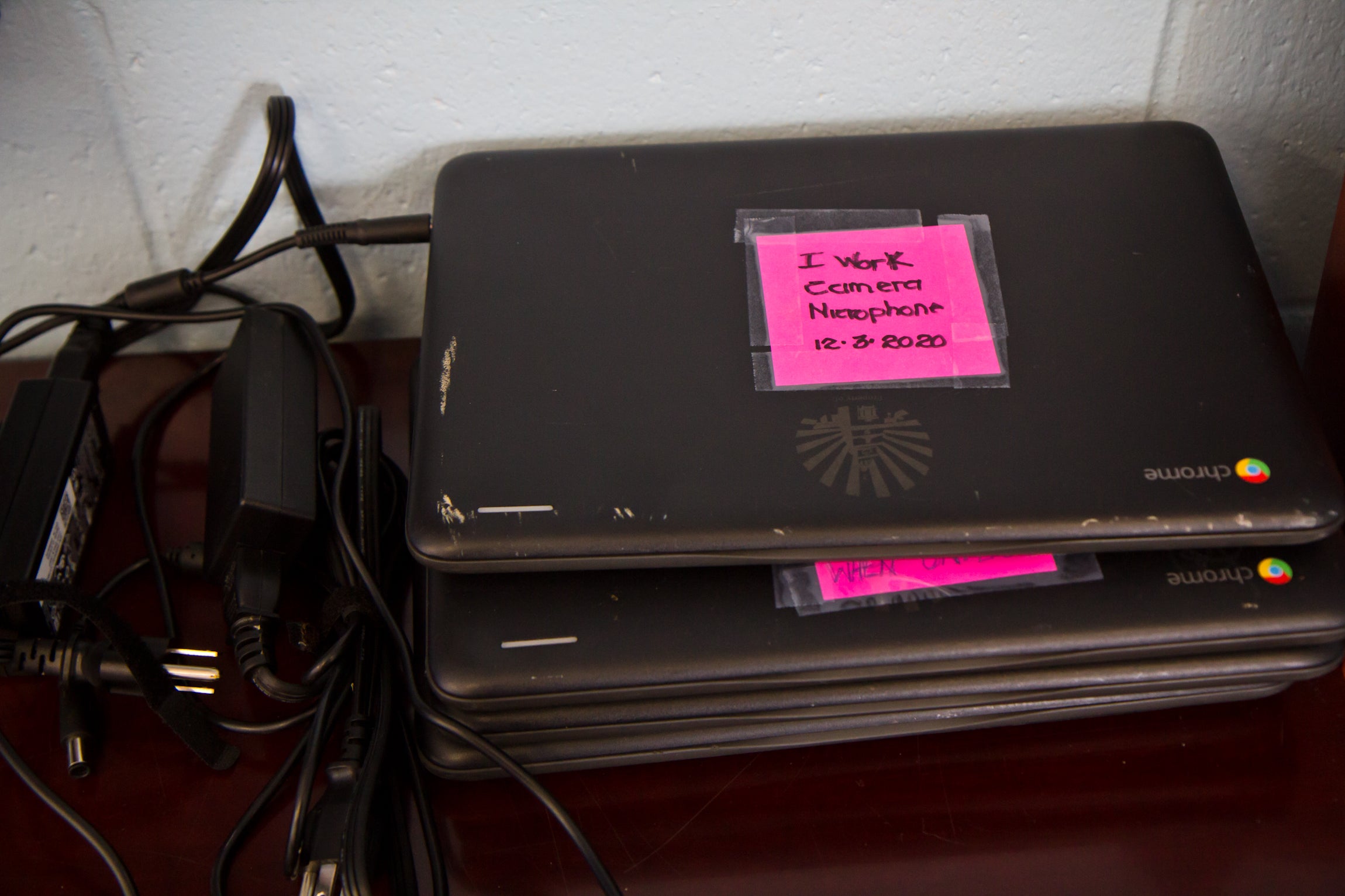

“We’re asking why aren’t you here? Why can’t we love on you today?” said Tolson. “If it’s because your internet’s not working, come to school. We have hotspots.”

The theme, Tolson says, is consistency. Families should know what to expect from their school — even more so now.

“Whatever we do, do it so people expect it,” said Tolson. “If they know they’re going to get a call by 2:15 every day if their child is absent, that’s consistency.”

When other strategies fail, Tolson assembles what she calls the “boots-on-the-ground dream team.”

About once a week, she and a few other staffers drive into their surrounding Cobbs Creek neighborhood and start knocking on doors. Often, the knocks echo into empty homes. Does the child live here? They can’t know for sure, so they keep coming back — to the point where the neighbors know their faces.

Even success stories are full of false starts.

Tolson says she made six visits to one house, each time receiving an apathetic response from the guardian that answered. Finally, on the seventh visit, a breakthrough.

“The parent said, ‘Well, you’re not gonna let this go?,’” Tolson recalled. “And I was like, ‘No, I’m not. I’m not gonna let it go. I’m fixated on your child coming to school.’”

It turned out the family needed a new laptop, which Tolson helped arrange.

Attendance is down slightly in Philadelphia’s public schools this year. But thanks in part to the tireless efforts of staffers, it hasn’t been a cataclysmic drop.

Through the school year, Philadelphia tracks attendance by publishing the number of students who attend school 95% of the time or more. In the first three months of the school year, those numbers were down. But as the chart below shows, December 2020 attendance was actually better than December 2019 attendance.

Still, there are notable racial disparities.

The percentage of Black and Latino students attending school 95% of the time dropped sharply at the beginning of this school year. While the gap narrowed in December, the overall picture remains troubling. Attendance for white students, meanwhile, is up over this time last year.

Persistence and partnership

For Tolson and other principals, fixing these trends requires a careful balance of persistence and partnership.

Everything can’t feel punitive. That’s why Tolson also makes home visits to deliver pizzas to children with exemplary attendance.

Principals know that many families feel overwhelmed. As much as they want children in school, they don’t want to feel like they’re strong-arming parents.

“When you speak to people you gotta realize they got more on their plate than their child just coming to school,” said Torrence Rothmiller, principal of West Philadelphia’s Andew Hamilton school.

Rothmiller gives the example of a mother whose child wasn’t coming to virtual school and felt out of options. After the school earned her trust, the mother revealed that her child has poor eyesight that made screen-learning difficult. Staffers found special glasses to ease the burden.

“It’s those small things that help you maintain that human touch,” said James Logan Elementary principal Chuanika Sanders-Thomas. “Yes, this is virtual. But we’re still here for you.”

Colette Butler is the community schools coordinator at Logan — acting as a sort of link between the school and the surrounding community in North Philadelphia. Her job involves a lot of text messages, push notifications, and routine check-ins.

Recently Butler chatted with a mother who had to make an extraordinary commute every day to drop her child off at a city-run program where virtual learning is supervised. Making that drop-off and then getting to work on time built into a knot of daily stress.

“She just broke down. She just said, ‘I’m tired. I can’t do this anymore. I’m overwhelmed,’” Butler recalled. “I think sometimes people forget that this is virtual school and we’re also in a pandemic.”

Bearing the load

For Andrea Surratt, principal at E.W. Rhodes, the reminders are everywhere.

One of her students logs on to school from Alabama, where the child now lives temporarily. Her staff is constantly dealing with dead phone numbers and letters marked “return to sender.”

The school is open daily from 9 a.m. to 2 p.m., and Surratt has filled a spare room in the front office with giveaways. There are goody bags, winter coats, books — anything that might convince a family to swing by the school and say hello.

Whenever a family picks anything up, Surratt has them fill out a contact sheet so she can get updated information.

“We have to stay connected to our families,” she said.

So far there are about 20 children the school has simply never seen. They’re on the roster. But they’ve never logged on. Despite phone calls and home visits, they’ve never made contact with the families.

Surratt knows some of those kids are out there. She hears about it from their friends.

These unseen children tend to be older — seventh and eighth graders who are mostly unsupervised during the day.

For those who skip school, it’s not necessarily because students want freedom or disconnection. Surratt knows some of them simply have too much responsibility to bear.

“A lot of the older kids are babysitting younger siblings,” said Surratt. “They’re so distracted.”

On a recent Friday, Surratt logged into a middle-school class to check in on some students. Sure enough, as soon as she entered, the students bombarded her with requests to leave school early.

“I gotta go with my aunt to her ultrasound,” said one.

“I have to go help my grandmother go shopping because she’s almost 70,” exclaimed another child.

Surratt listened patiently to the list of family obligations. Then she gave the students her blessing to duck out early.

“Just make sure your teacher knows,” Surratt reminded them.

Amid the commotion, she noticed one student not communicating at all. And she refused to let it drop.

“You need to respond,” she bellowed. “You know I’m gonna call your house.”

The boy knows that call is coming. Surratt can’t control much right now. But she can control that.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.