N.J. leaders agree affordability is a top priority, but limited consensus on how to get there

While there’s some consensus among Democrats and Republicans on what can be done to lower taxes in N.J., leaders have yet to offer a clear plan to do so.

New Jersey State Assembly in Trenton, N.J. (AP Photo/Julio Cortez)

Elected officials on both sides of the aisle in New Jersey say affordability is their biggest priority as the new legislative session gets underway and new lawmakers are sworn in.

Political leaders and some advocacy groups have different plans for dealing with the issue.

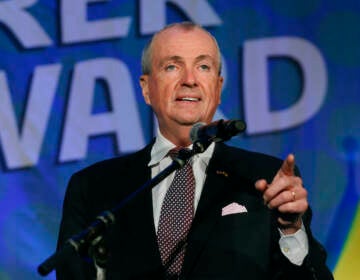

On Tuesday, as he took the oath for a second term after narrowly winning reelection in November, Gov. Phil Murphy promised to lower property taxes, though he did not specify how he would achieve that.

“Though property taxes are not set by the state, either by me or the Legislature, the decisions and investments we make directly impact their trajectory,” Murphy said. “Every dollar of new state funding for our schools and communities, for local roads and libraries, and for countless other areas is a dollar that stays in your pocket as a property taxpayer.”

In a poll released last November, the Eagleton Center at Rutgers University found property taxes was the number one concern for New Jersey residents. It, along with the close general election results, reaffirmed that this perennial issue and questions of affordability are still top of mind for residents, even amid the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

“Each of our administration’s first four years has ranked among four of the lowest year over year increases in property taxes, on record,” Murphy said. “But I’m not going to be satisfied with just slowing property tax growth. I want to get us to a place where we can begin to see them go down.”

New Senate minority leader Steven Oroho (R-24) said there are several ways to implement tax relief in the state: updating the state’s school funding formula to help districts in need (a point of consensus amongst Democratic and Republican leaders); creating a state-level deduction for charitable donations; using pandemic relief funds to restore the state’s unemployment fund instead of a planned tax hike on businesses; enacting pension and job benefit reform to shore up municipal budgets; and fighting a rule that allows New York employers to levy income taxes on employees who live in New Jersey and have worked from home since the beginning of the pandemic.

“We need to have the intestinal fortitude to say, ‘Hey, listen, things have to change,’” Oroho said. “So that’s what we’re going to be focusing on.”

General Assembly Speaker Craig Coughlin (D-19) said his caucus plans to tackle the issue by doing more of what he said has already worked:

“Things like the college affordability program that we passed last year. Things like renewing and fully funding the middle-class rebate or the senior tax freeze,” Coughlin said. “A middle class tax cut, which resulted in people getting some funding. We’ve increased child care, tax credits, and school meal programs.”

While state lawmakers and the governor don’t have the power to set property tax rates (only municipal leaders have that authority, using property taxes to pay for local schools, public works, emergency personnel, and county services), Coughlin suggested that state lawmakers can passively impact tax rates by imposing tax increase caps, such as a 2% cap passed in 2010.

Peter Chen, a senior policy analyst with the New Jersey Policy Perspective, said conversations around affordability should include all state residents, especially people on the “lower end of the income spectrum” — many of whom may not be homeowners.

“One thing that I’ve seen consistently that concerns me is that if property taxes are reduced on the landlord in landlord-tenant situations, it’s not necessarily clear that they’re going to say ‘Great, now I’m going to lower the rent,’” Chen said. “So I think that an important sort of thing to consider is how this ‘affordability mindset’ should also be reflected in housing policy.”

While state leaders said managing the ongoing coronavirus pandemic continues to be a priority for state leaders, especially following the recent surge in cases, they don’t see the threat of another shutdown.

“We’ve learned a lot during this past two years, and it’s time to get back to some sense of normalcy, and get the kids back in school and keep them in school and enable workers to get back … to work,” Oroho said.

Coughlin said the virus may stick around for years to come, but the prognosis seems “hopeful.”

“It seems to me that we’re headed in the right direction. While the number of cases is going up, the impact is less profound,” Coughlin said. “And so at some point, I guess we’ll have to live side-by-side with people getting it, and how we go about managing that well remains to be seen.”

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.