How the first lockdown saw more opioid-related overdoses among Black Philadelphians

Research by the city, Penn, and VA Medical Center found fatal and nonfatal opioid overdoses rose dramatically among Black Philadelphians in spring 2020.

Jennifer Shinefeld, a field epidemiologist in the Division of Substance Use and Harm Reduction at the Department of Public Health. She is at 24th and Oregon as part of an outdoor ‘pop-up’ to distribute naloxone. (Courtesy of the Philadelphia Department of Public Health)

Before the coronavirus, back in 2019, Philadelphia recorded 1,150 opioid-related drug overdose deaths and saw an increase in the rates of overdoses among Black and Hispanic residents, data from the city’s Department of Public Health showed.

Then along came 2020, bringing pandemic-level illness, death, lockdowns, job losses, and a reduction in safety-net services.

To measure the impact of all that on opioid-related deaths in Philadelphia, a team from the University of Pennsylvania, the city, and the Veterans Affairs Medical Center looked specifically at the racial breakdown of overdose deaths during the first lockdown. Their research, published in the medical journal JAMA Network Open earlier this year, found a dramatic increase in both fatal and nonfatal opioid overdoses among Black Philadelphians in spring 2020.

Among Black individuals, fatal overdoses rose from a monthly average of around 30 to an average of about 49 per month in April through June 2020. For white individuals, fatal overdoses dropped from an average of about 46 a month to an average of 35 a month during April to June of 2020. A similar trend was seen in nonfatal overdoses, which increased dramatically for Black individuals during the April-to-June period, while remaining fairly constant for white individuals. The study also took into account overdoses among Hispanic individuals, but rates of fatal and nonfatal overdoses seemed to remain fairly constant across the months studied.

That time frame marked a grim inflection point, said Kendra Viner, the city’s director of the Health Department’s Division of Substance Use Prevention and Harm Reduction, who was a member of the research team. Although opioid usage had been on the rise in Black and other communities of color, the second quarter of 2020 was the first time the overall number of Black people overdosing was higher than the number for white people, from June to April of 2020, 106 white individuals died, while 146 Black individuals died in the same time frame.

“I was certainly shocked by how rapidly that switch occurred,” said Viner. “We’ve been trending in this direction for a couple years, but I absolutely believe that COVID sped that transition up dramatically.”

The pandemic has not been easy on anyone, but it has not affected everyone equally.

“I think the stress has been particularly harmful to certain populations, and those include racial and ethnic minorities, people who have lower incomes … and, of course, people who have underlying addiction,” said Dr. Utsha Khatri, an emergency room physician and researcher at the University of Pennsylvania who was one of the authors of the study.

Andre Reid, a community activist and founder of the Philadelphia chapter of the National Alliance of Medically Assisted Treatment and of Lived Experience LLC, saw the pandemic setting back efforts at treatment. Before the virus, he felt like he was starting to “see a little daylight,” more people were getting into treatment. Then, he said, COVID-19 shut it all down and made things worse.

Medication-assisted treatment services were considered essential, and clinics offering buprenorphine and methadone were allowed to stay open during the lockdown; virtual meetings were organized for people in recovery. But, Reid said, “Now, you start adding new pieces to the fray. People lost their jobs, people lost their loved ones.”

He sees COVID-19 as yet another blow to communities that were already struggling. “You were already dealing with gaps in income, we were already dealing with gaps in health care … gaps in housing [and] with all these other health disparities,” Reid said.

Khatri described it as a “stress test” that highlighted inequity, structural racism, and pervasive problems in access and treatment. “A lot of these stressors brought on by the pandemic … are likely leading to increases in rates of substance use,” she said.

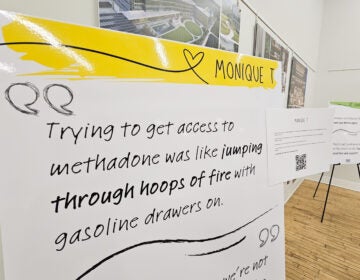

“Even before the pandemic, there were really stark racial disparities in accessing treatment for opioid use disorder,” Khatri said. “And in this time of extreme stress brought on by the pandemic, I think we have seen that those services that were available existed within the structures that were more available to white residents than Black residents.”

One example, she said, is access to Suboxone, also known as buprenorphine, a medication used to reduce dependence on opioids. Research has shown that Suboxone was less accessible to communities of color even before COVID-19. Reid, who is in long-term recovery from opioid use disorder, recalled that when Suboxone was first available in Philadelphia, it came from private clinics that required insurance.

Combining increased stress with fewer resources for help can yield deadly results. “This pre-existing disparity, plus the fact that we know that the pandemic resulted in the closure of a lot of clinics, as well as disruption of a lot of social service delivery, probably made this disparity even worse,” said Khatri.

Exactly what drove the switch in the numbers Khatri and Viner documented is still unknown. Among the Black Philadelphians in the study, the research team noticed a dramatic increase in the proportion of uninsured people, a trend that wasn’t seen in the overdoses among white individuals. Viner said she wasn’t sure what this data meant — whether job loss contributed to drug use, or if the economic situation brought on by the pandemic prompted people to seek out cheaper but less familiar narcotics. The pandemic, which brought stress and isolation, also cut out many of the safety net and social services that were already not distributed equitably. Viner and her team are currently working to understand how access to services like drug treatment, physical health care, housing support, meals, or insurance support changed during the pandemic and how that affected drug use. She does have anecdotal accounts from the families of people who have overdosed citing social isolation, job loss, stimulus money, release from prison, and an instance of an inability to connect access outpatient treatment as contributing factors.

Viner puts the start of the opioid crisis in Philadelphia somewhere around 2016 with the arrival of fentanyl, an incredibly strong synthetic opioid. With fentanyl came a dramatic increase in fatal overdoses, she said, adding that it “… really changed the game, because it just put people at much higher risk for dying of an overdose.”

Viner and Khatri cite fentanyl as a significant contributing factor to the increase they saw in overdose deaths.

“We think that during the pandemic, there have been changes in the drug supply networks,” said Khatri, who theorized that more drugs — opioids and non-opioids alike — are now contaminated with fentanyl.

Reid likened the situation to driving a car and briefly being distracted. “In the annals of time, they took their eye off the road for one minute to look at COVID, and before you know it, there’s a dent in the front of the car. And that dent was fentanyl and heroin,” he said.

Fentanyl can be found in opioids, but also in stimulants, cocaine, and methamphetamine, contamination that poses a serious risk. “We’re talking about populations of individuals who have basically no tolerance at all to opioids,” said Viner, “no awareness of the presence of fentanyl potentially, in the drugs that they may have been taking for years without a problem.”

Preliminary 2020 figures for opioid-related deaths show an increase over 2019, to roughly 1,210 to 1,220 from 1,150, Viner said. With more fatal overdoses, what are the solutions?

Reid said a partial answer may come through incorporating the experience and expertise of people from affected communities in the research, which he noted doesn’t always happen.

“If somebody comes in [there] with lived experience, [academic researchers] sometimes want to be critical of their information,” he said. “They feel as though the information didn’t walk the great halls of education.”

He thinks education, especially education coming from members of the community, is incredibly important — not only is to get the word out about fentanyl, but also to lay out the long-term consequences of habit-forming drugs. Reid said young people who are starting to use drugs like Percocet may not know they are taking a highly addictive opioid.

Although Viner said she had not seen this firsthand, she has heard stories of instances when researchers assumed they knew what was best for people who use drugs or were in recovery.

Stigma is still a barrier to treatment. “Science proves that addiction is a chronic disease, but we continue to treat it like a crime or a moral failing,” said Khatri, adding she believes that is especially true in communities of color.

“There’s so many patients that I’ve treated who have substance use disorders that hide it from their families, from their friends, sometimes even from the very doctors that are trying to help them, because of this fear of being judged,” she said.

Khatri is studying the experiences of Black individuals in accessing Suboxone.

“I think … as individuals who live in Philadelphia … we really have to embrace the principles of harm reduction,” she said. “For me, it means meeting people where they are, and showing respect and compassion for the lives of people who use drugs.” That’s best done, she believes by mitigating the risks to people who use drugs even if they are not ready to stop or go into treatment.

Viner said she and her department are working to better understand how and where people are encountering fentanyl in Philadelphia. Once they have a better picture of the situation, she said, she plans to launch a public information campaign. A new partnership with bars is something she is especially excited about.

“We’ve had a lot of interest from bars across the city, and what they’re doing is similar to how you see some bars with bowls of condoms on the bar, they’re actually going to be now bowls of fentanyl test strips,” she said.

The Health Department is also reaching out to communities of color. “We’re just now hiring a racial equity consultant for our division, and have formed a work group around developing a work plan specifically aimed at addressing the rise in overdose and drug use among the African American population,” Viner said. The department is also supporting six community organizations developing their own harm-reduction capacity, she noted, adding, “We’ll help provide technical assistance and resources, fentanyl test strips, and lots of things like that, but fully leaving it up to them to kind of build out the messaging that they know will speak to the populations that they serve.”

Reid is adamant that community organizations should be at the forefront.

“It’s not about age, it’s not about color, it’s about somebody who has enough empathy and wants to see change, and enough guts to make it happen.” he said, adding that more support is needed for grassroots organizations, education, and job training.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)