How Philly area scientists are looking out for the omicron variant

A leading scientist at the Penn lab that detected the first cases of delta says omicron will inevitably arrive here. He says the question is, “how much does it matter?"

A woman wearing a face mask crosses Broad Street, Wednesday, Nov. 18, 2020, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Matt Slocum)

Ask us about COVID-19: What questions do you have about the coronavirus and vaccines?

No cases of the new, omicron variant of the coronavirus have been detected yet in the United States, but health departments and genetic sequencing labs throughout the Philadelphia region are on the lookout.

Genetic sequencing is done through samples from positive test results sent to labs, which state health departments in New Jersey and Delaware run on their own. Pennsylvania doesn’t do any of its own sequencing, but sends roughly 35 samples a week to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The Philadelphia Department of Public Health is working with the Bushman Lab at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, which has been sequencing samples of the coronavirus throughout the pandemic and detected the first cases of the delta variant in the region last spring.

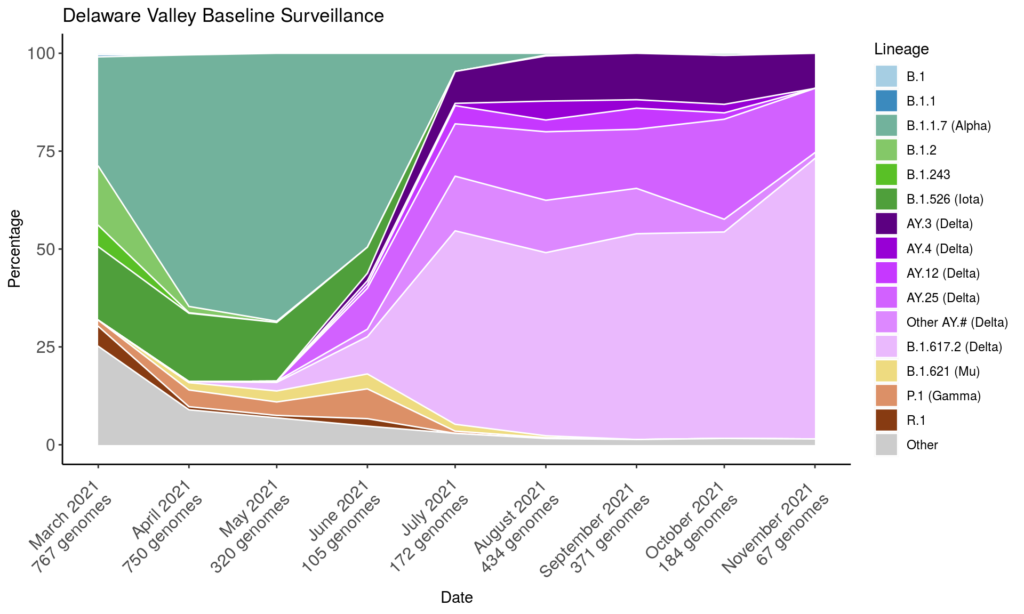

The lab receives most of its samples from a random subset of coronavirus patients at the University of Pennsylvania and has sequenced more than 4,000 samples to date. They aggregate the samples in a dashboard to show what percentage of cases are which variant, and how that has changed over time. As of late November, nearly all the cases sequenced were the delta variant.

As of Monday, the omicron variant had not been detected yet in the region, or in the United States, according to the CDC.

But Frederic Bushman, who chairs Penn’s microbiology department and runs the sequencing lab, said he thought it was likely only a matter of time.

“It seems inevitable, given how global the lineage is already, that we’ll see it here,” he said. “And then the question will be, well, just how much does it matter?”

A certain amount of viral mutation is normal if a virus still has hosts on which to spread, and labs like Bushman’s are tracking the various substitutions in genetic material over time. Many of those changes mean little or nothing for the impact of the virus on humans.

The changes in the omicron variant, however, concerned researchers who first detected it in South Africa because it has so many mutations that scientists had already cataloged as having recognizable and functional impacts, specifically on how infectious the virus is, and how well it may be able to dodge human immunity.

The most concerning mutations in omicron are in the spike protein — that’s the protein on the surface of the virus whose job it is to bind to the receptors on human cells, allowing the viral and human cell membranes to fuse. From there, the genetic material from the virus can enter the cell.

The substitutions in the spike protein in the omicron variant make that binding process easier, meaning it’s easier for the virus to infect human cells.

The spike protein is also a key tool in our ability to fight against infection; since it’s on the surface of the virus, it’s the target for the antibodies humans produce. Those antibodies can inactivate the virus’ ability to enter the cell by essentially getting to the spike protein and binding to it first, before the virus has the chance to fuse to the cells. Scientists are worried because the mutations in the spike protein in the omicron variant appear to make it harder for the antibodies to bind to the virus. That’s what health officials mean when they say it’s possible this variant could evade human immunity.

Bushman said the omicron variant also has changes to an entirely different protein, one found inside the virus called the nucleocapsid protein, that help it encode and store mRNA material more efficiently.

It’s too early to know just how impactful the new variant’s ability to infect human cells and get around human immunity will be. If it does turn out that omicron has outpaced the antibodies produced by the mRNA vaccines, Bushman offered a couple of potential silver linings.

The first is that mRNA vaccine developers can tweak the vaccine formula to target the new mutations just as easily as sequencing labs like his and the one in South Africa that first detected omicron can identify new viral lineages.

“It once was a very complicated process,” said Bushman. “Today, actually, it’s much easier, thanks to the mRNA vaccines. You just need to know the sequence.”

He noted that the greatest obstacle in updating the vaccines would not be the scientific process itself, but the time constraints involved in testing the safety profile of any vaccine adjustments.

Bushman also pointed to a theory, which posits that because pathogens evolve for efficient spread, their mutations may lead them to be more infectious, but also more benign so as not to kill off all their potential hosts. While there is some very early evidence indicating the omicron variant may lead to milder illness — the first infections were reported among younger people who tend to experience less severe symptoms — Bushman cautioned it’s too soon to say yet whether this is the case.

In a statement, the Philadelphia Department of Public Health advised everyone to continue to avoid crowded, indoor spaces, and to consider double masking if it’s necessary to go into one. The department also recommended everyone gets vaccinated or boosted who has not done so.

The Pennsylvania Health Department also promoted getting vaccinated, and stressed that another lockdown would be unlikely to defend against any new wave that the omicron variant might drive.

“While capacity restrictions in businesses and restaurants were part of our mitigation strategy early in the pandemic, Pennsylvania is in a very different situation now and we are more prepared now than all prior variants,” said Deputy Press Secretary Maggi Barton in an email.

During his weekly coronavirus briefing on Monday, New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy said the state’s Department of Health is ready to sequence and detect the variant.

The governor said he “would be stunned” if omicron is not already present in the United States, but cautioned that the delta variant is still the current threat phasing the Garden State. He also urged residents to get vaccinated or boosted.

“Just because a new variant is out there, doesn’t mean delta has lost any of its transmissibility …,” he said. “Our numbers are still being fueled by the delta variant.”

WHYY News’ Laura Benshoff contributed reporting.

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)