Coronavirus emergency results in major cuts in city spending on affordable housing

Gym said the top issue she is hearing from constituents are concerns about paying rent. The mayor’s budget would slash spending on affordable housing.

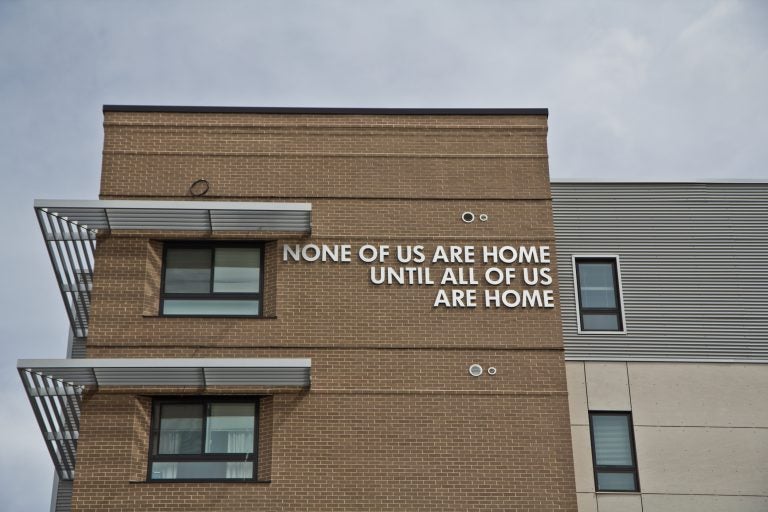

The Ruth Williams House at Broad and Boston Streets in Philadelphia has 88 units for those in need of affordable housing. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Mayor Jim Kenney is taking flack over cuts to city affordable housing programs that critics say could hurt families and communities already hit hard by the coronavirus pandemic.

Among the many reductions included in Kenney’s post-pandemic budget is one that will cost the city’s Housing Trust Fund some $14 million. The money previously earmarked for the city’s dedicated affordable housing fund, under the current plan, would go into the city’s general operating coffers.

The Philadelphia Eviction Prevention Project — which provides lawyers for renters in landlord-tenant disputes — and a recently unveiled rental assistance program would also succumb to cuts.

Some $16 million from a now-exhausted bond that paid for low-income home repairs will not be replaced, while millions more set for the creation of new affordable housing will be reallocated for rental assistance.

At-large City Councilmember Helen Gym blasted the plans to effectively eliminate PEPP with a 75% cut to its $2.1 million budget. Gym, who has challenged the Kenney administration’s budget plans during ongoing hearings, said in an interview that she has concerns about what appeared to be a broader divestment in the city’s housing programs.

“I’m definitely concerned about any proposal that would move funding away from housing,” Gym said. “People being able to make their rental payment is the top issue coming into our office today.”

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

The city budget was revised in April to account for a $649 million COVID-19 related revenue shortfall. While the administration acknowledged upwards of $40 million local housing revenues were being eliminated, early budget briefings indicated that emergency funds from the Department of Housing and Urban Development CARES block grant would largely “backfill” losses to a planned $134 million housing budget.

But some on City Council, like at-large Councilmember Kendra Brooks, grew skeptical that federal funds would or even could replace all of the eliminated programs.

“I worry that the restrictions that come with federal funding might limit the city’s ability to protect affordable and accessible housing,” Brooks said.

The city was set to reap some $14 million in new revenue from expiring 10-year tax abatements to bolster the Housing Trust Fund, which pays for a variety of programs. But, under the proposed budget, those excess funds will instead flow into the city’s general operating budget, effectively eliminating $5.57 million set for the maintenance of affordable rental housing and another $5.7 million in downpayment assistance for the Philly First Home Buyer program.

It was Kenney’s administration that, in 2018, committed the new funds in exchange for City Council agreeing to withdraw a proposed 1% tax on construction. Council pitched the construction tax as a dedicated source of revenue for the trust fund. Kenney said then that the abatement revenue would provide a “reliable” source of cash for affordable housing.

Beth McConnell, policy director of the Philadelphia Association of Community Development Corporations, said it was unfair of Kenney to effectively back out of a deal his own administration had brokered.

“Mayor Kenney committed to a schedule of funding that included at least $14 million this year,” she said. “Backing out of that agreement will result in fewer Philadelphians having a safe place to call home at a time when having a home is how we stop the spread of COVID.”

Millions less for affordable housing creation

An array of planned programs aimed at vulnerable renters, known as PHLRentalAssist, will also evaporate through $6 million in proposed cuts to the Department of Planning and Development. The program attracted attention for providing no-strings-attached cash assistance to 1,000 low-income families for up to a year.

The city will instead channel federal funds to 4,000 families this year using federal emergency funds. But because these dollars will be drawn from HUD, federal guidelines will limit rental assistance to just three months, with far stricter eligibility requirements than what the city had proposed.

What happens when these funds are depleted is also unclear. Paul Chrystie, a spokesperson for the city, did not provide specifics about how emergency federal funding would be replenished in future years.

Other programs will be effectively defunded with no alternative in place.

The Housing Trust Fund also receives dedicated revenue from mortgage and deed recording fees, but the city has revised down these expected collections –– due to a likely economic recession –– to about $8 to $10 million from $12 to $14 million generated in 2020.

Under the current budget proposal, this reduction will lead to about $3.8 million less spent on the creation of new affordable rental housing, with most remaining funds earmarked for rental assistance and weatherization programs.

Separately, a $100 million bond, funded through an increase to the city’s real estate transfer tax, has been exhausted. About $60 million of this had been allocated to clear out a backlog to the city’s Basic Systems Repair program, which provided emergency maintenance funds to low-income homeowners.

Although the city will still allocate about $10 million in federal emergency funds for BSR, the failure to replace existing bond funding means that program will shrink significantly from the $24 million seen last year.

City spokesperson Chrystie said some programmatic cuts were reflective of the city refocusing resources away from new development and toward rental assistance.

“The City’s housing priority right now is to keep people in their homes and so some funding has been shifted from housing production to meet this immediate need,” he said.

But Chrystie acknowledged that some of the budgetary pain was real and reflective of the deep fiscal crisis facing the city.

“None of this is to say that the City will come close to meeting the increased housing need. It won’t. It is what is doable given the enormous hole in the City’s budget caused by COVID,” he said. “It is why the federal government needs to step up and support states and cities across the country that are facing budget crises not of their own making.”

To some council members, like Brooks, these cuts were short-sighted. She predicted that the city would only face more severe long-term costs as evictions and foreclosure moratoriums expire.

“There is an eviction and homelessness crisis at our doorstep and housing is the last place that we want to be making cuts, at a time when Philadelphians need housing protections more than ever,” Brooks said. “Housing is not only a basic human necessity but the cornerstone of protecting public health. Our city budget must reflect that.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)