The Frankford El celebrates its centennial: 100 years of connecting neighborhoods to Center City

Residents have simultaneously appreciated and disdained the Frankford El since it debuted in Philadelphia 100 years ago.

Listen 5:14

The Market Frankford train approaches Somerset Station. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

When the Frankford Elevated Railway debuted on Nov. 4, 1922, the Evening Public Ledger published a whole special section dedicated to the new extension of Philadelphia’s subway system. “All Aboard! ‘L’ Brings Frankford Joy,” crowed the main headline.

“Frankford ‘L’ a Triumph of Modern Engineering Skill and Ingenuity,” another headline read. “Anti-Noise, Anti-Accident, Anti-Delay Devices Make It Most Up-to-Date of Transportation Structures. Means a Vast Expansion of Northeastern Section.”

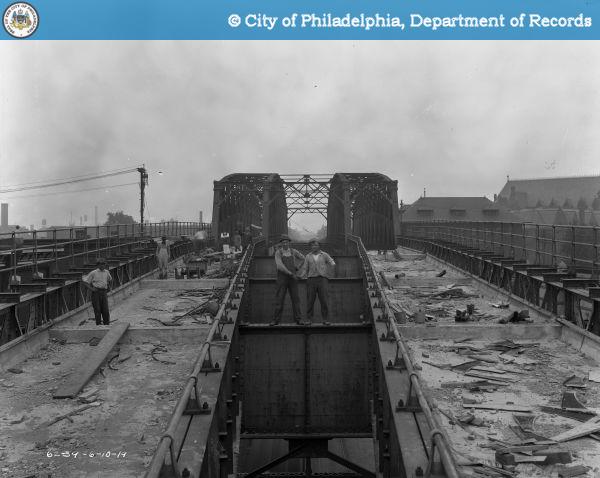

The long-awaited, 6 1/2-mile line had taken seven years to build and cost $11.6 million, equivalent to more than $200 million today. For the first time, people living in the Northeast had a way to get to Center City in an hour or less. The line boasted innovations like concrete in the support beams to reduce vibration and noise from passing trains, and railcar doors that automatically retracted if they bumped a passenger.

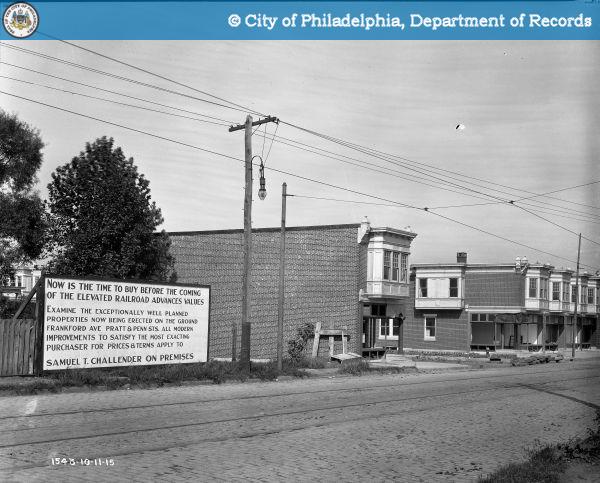

The excitement at the line’s opening reflected a conviction that the city was poised for more of the continual population growth it had seen over the previous century, said John Hepp, a retired Wilkes University professor who studies Philadelphia’s transportation history. That was especially the case for Holmesburg and Bustleton, which were rural areas ripe for residential development. Now, they could be reached by trolley from the El terminus at Bridge Street in Frankford.

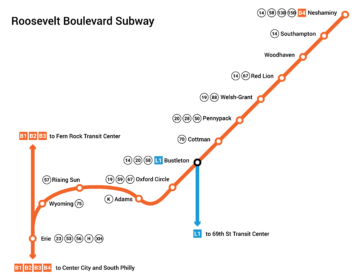

Hepp, who lived in Frankford as a child, noted that planners had sketched out several potential new subway lines — a Roosevelt Boulevard line, a Southwest line, and two Center City loops, among others — but the Frankford extension was one of the few that was actually built.

“I’m sure when this line was opened, everyone’s mindset was ‘Oh my god, Philadelphia has its act together,’’ he said. “‘Philadelphia made plans, Philadelphia’s carrying through on this plan, and the future is nothing but bright. In 100 years it’s going to be a city of 5 million people.’”

As SEPTA prepares to commemorate the Frankford El’s centennial anniversary, Hepp and others say the line did help drive a transformation of the kind city leaders anticipated, especially in the boom years following World War II. Frankford Avenue became a major shopping corridor and the greater Northeast saw a historic wave of large-scale housing development. More recently, proximity to the El has contributed to redevelopment in areas like Northern Liberties and Fishtown as car-free urban living has become newly popular among a younger generation.

But the evolving role of the Market-Frankford Line and the subway system overall, which first opened in 1907, has also reflected broader societal changes that in some ways left it behind. Ridership peaked in the 1940s, due in part to rising auto ownership, highway construction, and suburbanization. Philadelphia now has fewer residents than it did in 1922, and Frankford is economically depressed. SEPTA has struggled to manage the impacts of homelessness and drug use on the system and to reverse a collapse in ridership caused by the pandemic.

“It’s a neighborhood asset that’s utilized — and under-cared for,” said Kimberly Washington, executive director of the Frankford Community Development Corporation. “The El could definitely use a little bit more TLC. The city and SEPTA and state officials definitely have to figure out a way to build people’s trust in the public transit system, and make people feel like they want to ride the public transit system.”

‘Overcrowding at all hours’

Residents have simultaneously appreciated and disdained the Frankford El since it was first proposed. Hepp said that during a presentation he gave at the Northeast Philadelphia History Fair in April, an audience member recalled that his grandfather had been a member of a local business association that lobbied against raising the line’s “ugly” columns and girders over then-quaint Frankford Avenue.

“Who wants to see the sunlight obliterated and big, metal, ungodly, structures in the middle of your main thoroughfare?” said Jack McCarthy, an archivist and historian who previously worked at the Historical Society of Frankford. “All that metal and steel — it was just not a very pleasant visual.”

The environment around the El has also been shaped by the continuous rumbling of passing trains, which for decades ran 24 hours a day. The noise gave rise to the “Frankford Pause,” in which conversations on the street stop until the El goes past, McCarthy said. A green space next to Arrott Transportation Center is called Pause Park.

Yet despite the El’s unlovely appearance and thunderous noise, it was a huge success in its early years. So intense was demand that in April 1930, the 300 members of the Business Men and Taxpayers’ Association of Frankford voted to denounce its “inadequate service.” The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that they accused the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company, or PRT, of running fewer trains with fewer cars.

“There is overcrowding at all hours of the day, and during rush hour it is far greater than it used to be,” association director James France said.

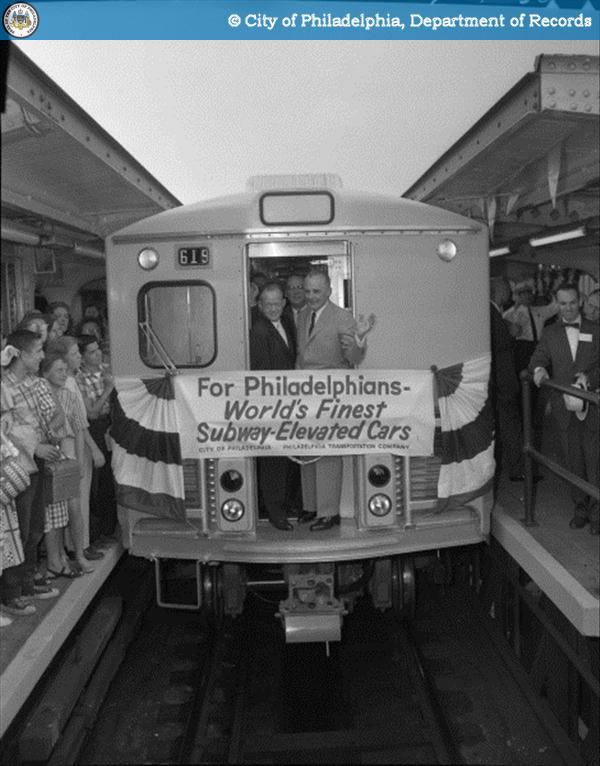

At the time the businessmen would have been riding in the El’s Brill A-15s, red railcars with many windows and “really terrible” interiors that maximized standing room rather than seating, according to Hepp. In 1960 the PRT’s successor, the Philadelphia Transportation Company, replaced them with stainless steel cars nicknamed “Almond Joys” for the smooth nut-like bumps on their roofs.

The bumps housed ventilation fans but not air conditioning, which the city could not afford. “In the summertime, it’s amazing how hot the cars could get,” Hepp said. SEPTA took over the transit system in 1968, and in the late 1990s introduced the current cars, called M-4s, which finally brought air conditioning as well as modern features like automated announcements to the Market-Frankford Line.

The route of the Frankford El changed slightly in the late 1970s, when the construction of I-95 through Center City led to relocation of the line to the highway median and construction of Spring Garden Station to replace the old Fairmount station. Between 1987 and 2000 SEPTA completely rebuilt the line to address long-standing structural problems, although design flaws caused some of the new concrete to crumble and required further repairs.

A huge challenge

A major concern and challenge since the Frankford extension opened has been rider safety. Even in the 1920s, the PRT tried closing some stations at night to save money and avoid situations where someone could be waiting on a platform alone, Hepp said. Streets in the industrial, working-class neighborhoods north of Center City could be rough places, he said, and some blocks have intermittently served as open-air illegal drug markets for decades.

“The Frankford El has always had a somewhat mixed reputation,” Hepp said. “Well before I was born, the corner of Kensington and Allegheny” — where Allegheny Station is located — “was considered a fairly tough neighborhood.”

Recently, issues with drug use and people who are homeless sheltering in stations came to a head during the pandemic. SEPTA closed Somerset Station for two weeks in March 2021 to fix elevators damaged by urine, human waste, discarded needles, and other trash, and to make other repairs and deeply clean the facility. Allegheny and other stations underwent similar makeovers. SEPTA also posted transit police officers and social outreach workers to the stations.

Kim Scott Heinle, SEPTA’s assistant general manager for customer service and advocacy, says staff work around the clock to keep the El clean and safe, and customer complaints about those stations have dropped significantly since last year. But he acknowledged that SEPTA continues to grapple with the “unchecked” quality of life issues that plague the city.

“We have a huge challenge to convince people that despite what they see around them, you can safely ride SEPTA,” Heinle said. “Are you going to encounter things that are not pleasant all the time? Yeah, you will, but you’ll see the same things other places. That’s just the nature of the beast right now.”

“I think it’ll change, but it really requires a partnership at all levels of our government and communities to come together and let people know what’s acceptable and what’s not acceptable,” he added.

Kimberly Washington, head of the Frankford CDC, noted that SEPTA just launched a new social services and cleaning program for stations, and said it’s essential that such efforts continue in order to build public trust in the transit system.

She also wants SEPTA to continue supporting efforts to boost the local economy around Frankford Transportation Center, the El’s busy terminal station. A reconstruction of the FTC in 2003 improved the facility, but the project was ultimately “sort of saddening” for residents because SEPTA installed amenities like a donut shop and pizza place inside, rather than encouraging people to step outside and shop on Frankford Avenue, she said.

The Frankford CDC is working with SEPTA and property owners on a plan to replace a shuttered Thriftway supermarket near the station with new stores and housing. Washington said the FTC, which is serviced by more than a dozen bus lines that bring in riders from around the Northeast, could still be a catalyst for neighborhood improvement.

“We see the SEPTA station as being a real asset to the neighborhood, and to the commercial corridor, that we’re really trying to leverage. It brings a ton of folks through the neighborhood, but they really don’t have a reason to stop and shop,” she said. “We’re looking to put something there that will draw people off the El and revive Frankford Avenue to the great shopping district that it used to be.”

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.