Our plastic footprint sinks, right to the bottom of the sea

Researchers are discovering that plastic doesn’t just float on the sea's surface. Mass amounts rain all the way down to the seafloor, filling the guts of deep-sea organisms.

Listen 12:45

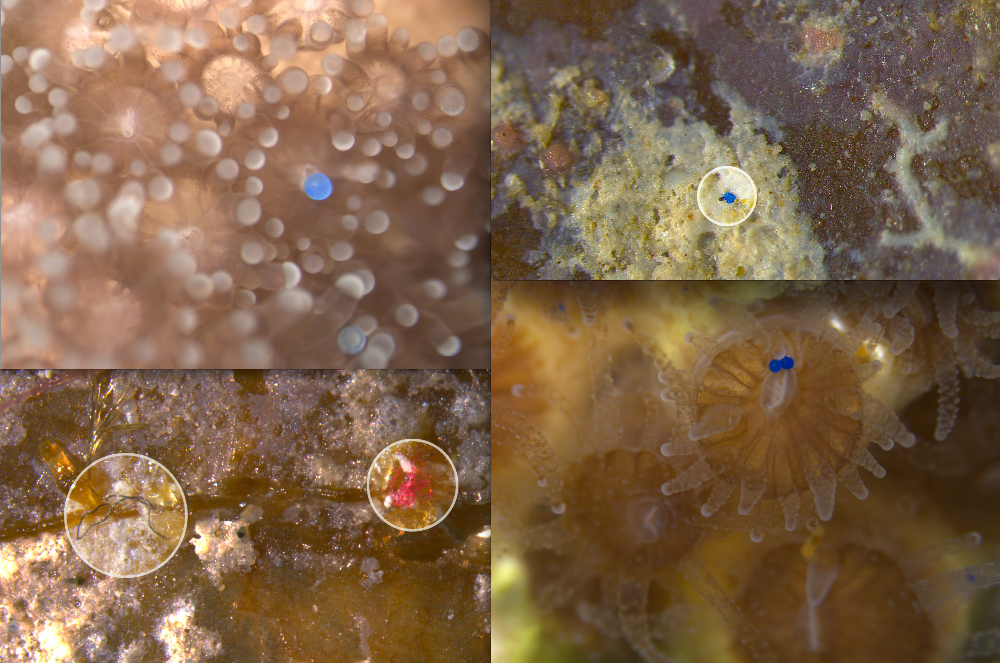

Every year, 8 million tons of plastic flow into the ocean and break down into microplastics. Because many organisms eat them, microplastics have the potential to crash marine ecosystems and leach poisons into our seafood. (Photo by Zikri Maulana / SOPA Images / Sipa USA, via AP Images)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.

When we think of plastic in the ocean, we tend to think of it floating on the surface. Maybe you’ve heard of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, and envision an island-sized carpet of trash floating in the middle of the sea? In fact, it’s so much more than that.

“That’s just the literal scratch on the surface,” said Randi Rotjan, a research assistant professor and marine ecologist at Boston University.

All that trash breaks down into tiny particles, practically invisible to the naked eye, called microplastics. In the past decade or so, scientists have started finding plastics and microplastics in every part of the ocean they’ve visited.

Microplastics are suspended all through the ocean, at every depth, and buried in the seafloor, too, Rotjan said. They are more like flecks of spice and seasoning distributed through a bowl of soup than spots of fat you can skim off the surface.

Though Rotjan spends a lot of her time studying plastics, she doesn’t particularly want to be a plastics researcher.

“I don’t really have a choice,” she said. “Plastic keeps showing up in all of our samples. Every sample we’ve looked at, in any ecosystem that we’ve looked at across the globe, plastic has been part of the story, and it’s been impossible to ignore.”

Plastic entrenched

Rotjan is also the co-chief scientist of the Phoenix Islands Protected Area, in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. To get there, you have to travel seven days by boat from Hawaii.

Even there, in a protected area, in one of the most remote places on Earth, scientists finds plastics enmeshed in samples they take from the sea’s surface.

“And those are all typically microplastics that are floating in a place that’s so far away, that the closest people to us when we’re out there are on the International Space Station,” Rotjan said.

Rotjan and other researchers are starting to suspect that there’s no part of the ocean left untouched by plastic. Recently, a study found, for the first time, that tiny deep-sea creatures living in the Pacific’s Mariana Trench are eating staggering amounts of plastic.

The Mariana Trench is 36,000 feet below sea level. It’s a zone where the ocean floor is sinking into the interior of the Earth, going deeper and deeper until it melts. If you were to take Mount Everest and drop it in the deepest part of the trench, you’d still have more than a mile of water above it.

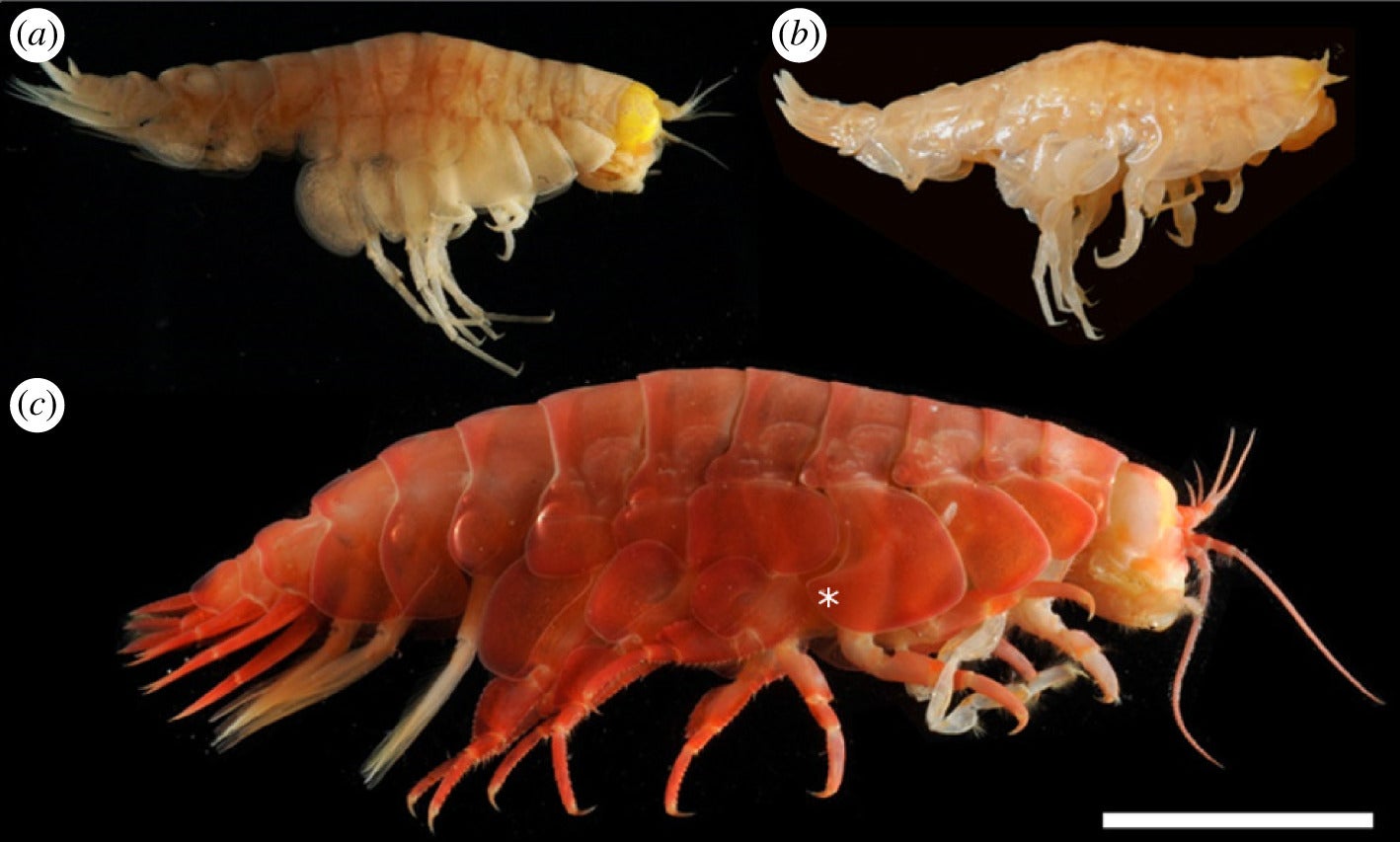

Even in that abyss, there’s life. Specifically, little shrimplike creatures called amphipods, about the size of the pull-tab on a soda can.

The researchers found plastic in the guts of more than 70% of the amphipods they collected. They also found high levels of toxins called PCBs in the amphipods’ bodies.

Journey to the sea

To understand how plastic ends up in the deep sea, we have to look to land.

Every year, “8 million tons of plastic leave land, down drains, streams, rivers, and waterways flowing into the ocean,” said Emily Penn, the co-founder of eXXpedition, a group that runs all-women sailing voyages around the world to raise awareness about plastic pollution.

Subscribe to The Pulse

That’s equal to dumping a garbage truck full of plastic into the ocean every minute.

There are many ways plastic gets into the ocean. Many countries dump their garbage directly into it. In countries with trash collection, plastic escapes on its way to and at the landfill, then flows downstream. Even recycling isn’t off the hook — globally, only 9% of plastic is recycled.

All that garbage is considered macroplastic, which ends up in the ocean. It’s worn down by the sun’s UV rays, waves, and wind action, and eventually becomes microplastic.

There are also a couple big, direct sources of microplastics: as your car tires wear down, little fibers come off and go down storm drains. Then there are the fibers that come off the synthetic fabrics we wash in our washing machines. Think of all the stuff in your dryer lint, draining into the ocean.

Of the 8 million tons of plastic that leave land every year, researchers estimate only a quarter-million ton is floating on the ocean’s surface. So the big question is: Where is the rest of it?

“What we expect is happening is that it’s actually sinking,” Penn said. “Particularly when it gets out to these deep parts of the world, and it gets coated in algae, it gets barnacles that grow on it —and then that makes that plastic heavier than water and it sinks to bottom.”

Both macroplastics and microplastics rain down into the deep ocean, and that’s how plastic gets in places like the Mariana Trench — and ends up in our deep-sea friends, the amphipods. Rotjan, the marine ecologist, said plastic in these little guys’ guts is a big deal.

“It has the potential to crash food webs, right?” she said. “Their bellies are full, but they have no nutrition because they’re full of microplastics instead of food. I mean, that just doesn’t bode well for the continuation of healthy marine ecosystems.”

Plastic and us

Those plastics could come back to us. After all, we’re at the top of those food webs.

For Angelo Villagomez, who grew up in Saipan, the largest of the Northern Mariana Islands, plastic and PCB pollution in the Mariana Trench isn’t some distant problem.

“I don’t think of it as this far off place. I think of it as there’s plastic and pollution in my backyard. And this is the backyard where we’re catching our dinner — that’s where we got most of our food,” said Villagomez, who now works for the Pew Bertarelli Ocean Legacy Project, based in Washington, D.C., fighting for the creation of marine protected areas.

The possibility that plastics are entering wild food chains particularly affects indigenous communities, Villagomez added. His own family is Chamorro, the indigenous people of the Mariana Islands.

“Indigenous people as a whole, our diets consist of wild animals more than other folks’,” he said. “So if these poisons are leaching into the food that we’re eating, those poisons are then leaching into us.”

Plastic has toxins in it — things like PCBs, BPA, and phthalates, which have been associated with cancer and hormone disruption. On top of that, plastics are probably absorbing other chemicals in the ocean, like pesticides, which have also been linked to disease.

When we eat seafood, we’re not directly eating much plastic, because most of us don’t eat the stomachs of fish. But the concern is all these toxins are seeping from the guts of marine animals into the rest of their bodies, and making their way up the food web.

That isn’t good, because the most harmful chemicals aren’t digested — they stick around. In a process called biomagnification, higher-level predators, like us, tend to build up higher and more dangerous concentrations.

It might be decades before scientists have proof of cause and effect. Plastic is hard to study in humans for a couple reasons. First, it’s impossible to find a control group of people not exposed to plastics — we’re all exposed — all the time. And second, many of the problems that might be linked to plastic — like cancer or reproductive problems — can take a long time to develop.

But Penn, of eXXpedition, feels there’s enough cause for concern that countries need to come together to tackle the ocean plastic problem now.

The fact that the deep sea may be the largest reservoir of plastic waste on the planet makes cleanup really tricky, she said. “It goes from what was already a hard challenge — cleaning up on the surface of the ocean — to a near impossible challenge, when we talk about cleaning up plastic on the seabed, which might be five miles down.”

So our best bet, Penn said, is to reduce the amount of plastic we’re using on land. Since our lives are so intertwined with plastic, advocates say, it’s going to take a multipronged effort to change things.

They say the big polluters in industry have a responsibility to reduce their plastic footprints and come up with solutions, such as compostable materials, or new ways to reuse discarded plastics. In addition, governments should incentivize and support these shifts. A good first step would be standardizing the plastic we use to just the few types that can be recycled, and implementing a deposit return scheme. That could do a lot to increase recycling rates, Penn said.

Lastly, advocates recommend that consumers try to reduce the amount of plastic in our lives — particularly single-use plastics, like that styrofoam cup you use one time and throw away. Because plastic is a material that’s designed to last forever, using it one time doesn’t make much sense.

The good news is, the ocean is resilient and generous.

“If we can just work out our little piece here on land,” Penn said, “we can enjoy the benefits that the ocean brings us — the oxygen in the air that we breathe, the water we drink, the foods that we eat — for many more generations.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.