Philly program steps up efforts with families, schools to address early psychosis in kids

Psychosis is a set of experiences that relate to finding reality confusing or unclear. Not all people who experience it have schizophrenia.

Listen 4:54

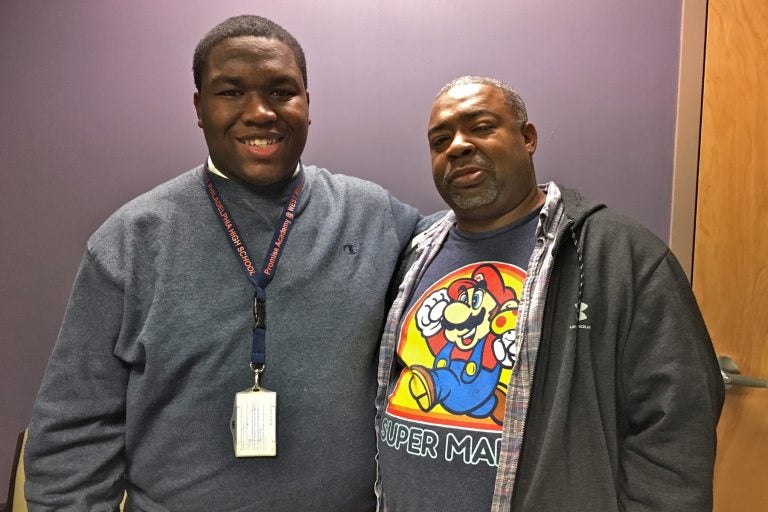

Ahmad Harrington (left) stands beside his father, James. Ahmad has learned skills to cope with psychosis at the PEACE Program. (Anne Hoffman/WHYY)

Ahmad Harrington is excited about his upcoming 17th birthday.

The Northeast Philadelphia resident is confident, hopeful, and happy. But, like most teenagers, he’s pretty existential.

“I’m always thinking ahead of myself,” he said. “I’m always wondering about myself.”

He thinks about girls a lot — and then he asks himself, why am I thinking about girls so much? In part, it’s because he’s analytical, but he’s also started watching his thoughts more as part of his treatment for psychosis.

Ahmad’s program is called PEACE, which stands for Psychosis Education, Assessment, Care and Empowerment. It’s a program that works with teens and young adults who have early-onset psychosis. He goes there for individual and group therapy. The program includes the young person’s whole family.

Psychosis is a set of experiences that relate to finding reality confusing or unclear. Not all people who experience it have schizophrenia. Ahmad doesn’t, for example.

“It can be schizophrenia, it can be bipolar disorder, it can be trauma induced, it can be substance induced, all of those,” said Irene Hurford, a psychiatrist and the clinical director of the Philadelphia-based PEACE program.

Ahmad has bipolar disorder, and psychosis can be a feature of that. These days he has fewer visual hallucinations, but they still happen from time to time.

“I see small things, like I might see a fly go by. It might not be there, I might try to grab it and it won’t be there,” he said. “Sometimes, it actually is a bug, and it’s like flying really fast.”

Just two years ago, Ahmad was terrified of his racing thoughts. It was those thoughts — telling him to hurt a teacher — that convinced Ahmad’s mom he needed to go to the hospital.

His dad worked in the mental health field for a number of years, and his mother has had her own mental health struggles, so they knew the importance of not letting him try to get through this on his own.

It turns out that’s crucial when it comes to psychosis.

Early intervention and education

“The earlier you are able to intervene, the sooner you can put in place tools and supports that are going to help people be successful,” said Ashley Park, Ahmad’s therapist. “The longer that people are ill, generally, the more disruptive an experience they have.”

A lot of data going back several decades support that idea, said Hurford.

“Functional and quality-of-life outcomes are better,” she said. “People have fewer relapses, fewer hospitalizations. So, in many ways, catching it early confers benefits for the rest of the person’s life.”

A lot of the program is about psychoeducation — or helping people understand their illness and helping their families support them as well. Program leaders want to reach out to schools next because they could offer an ideal opportunity for early detection. As it stands, kids are often misdiagnosed or simply missed at school.

“We have met with school district officials to inform them of early warning signs in hopes that they can refer someone to us for assessment prior to their first break” or hospitalization, said Marie Wenzel, the PEACE program director. “Our goal is to intervene as early as possible.”

A family approach

Ahmad’s dad, James Harrington, has always acted as an advocate for his son — ever since teachers started reporting behavioral issues when Ahmad was young. Playing an active role in his son’s mental health care is almost like another job.

“You have to be prepared to deal with this stuff. All society knows this, especially … as a black man, all society knows is to lock them up,” he said. “That’s the way it is.”

Parents often feel a sense of hopelessness when their children are diagnosed, Hurford said

“The care is often fractured and inconsistent. And, meanwhile, the child continues to suffer,” she said. “So I think, for parents, it’s a very frightening and isolating experience, and there’s also a lot of stigma attached to the experience of having a child with a psychotic illness.”

PEACE tries to bring in families from the beginning and then offer thorough treatment.

Harrington said he’s had to learn how to talk to Ahmad so he doesn’t trigger him. He’s learned to be sensitive to his son’s needs and validation of his experience.

That can be hard, and other family members have had different opinions.

“Some people look at Ahmad and say, ‘Ain’t nothing wrong with him, he’s just tripping,’ ” Harrington said.

But he does not react. He just listens and says, “Yeah, Ahmad will be all right.”

To break that kind of isolation and create support, PEACE has groups for families going through the same experience. When parents get that support, they’re better able to be there for their kids, said Wenzel.

‘I can snap out of it now’

As for Ahmad, he’s learned from his sessions with his therapist what to do when he sees that telltale bug.

“You know, sometimes I’ll actually notify people, like, ‘Dad, have you seen that?’ ”

That’s called reality testing, and it’s something he’s working on at the program.

As he looks forward to his birthday, Ahmad is feeling hopeful about the future — even though he still gets pulled into his mind sometimes.

“I could be writing, just finishing the test, and, boom, I’m daydreaming again,” he said.

But he said there’s a difference: “I can snap out of it now. Back then, I’d be in it until someone calls my name or something happens.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.