Wrongfully evicted in snowstorm, blind man and daughters ‘elated’ by court clearance to resume lawsuit against Delaware

The eviction order was for a previous tenant, but a state court said the landlord “weaponized” the process to remove the Murphy family.

Listen 2:26

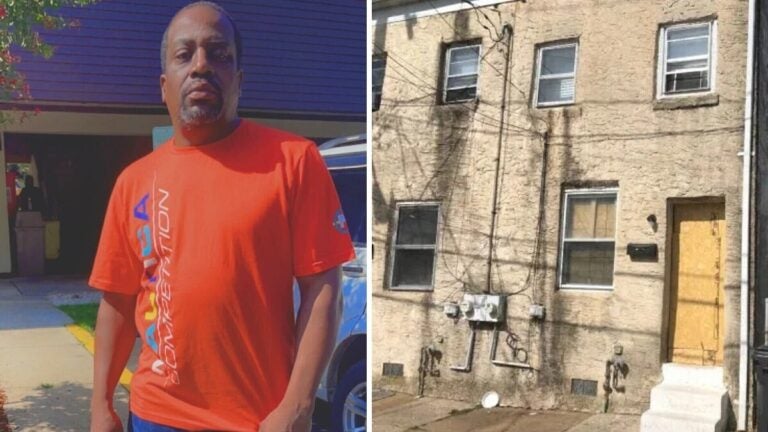

William Murphy, who is blind, can now resume his family's lawsuit against the state over being wrongfully evicted from their home in Wilmington's Southbridge section during a snowstorm in 2021. (Courtesy of William Murphy, Cris Barrish/WHYY News)

What are journalists missing from the state of Delaware? What would you most like WHYY News to cover? Let us know.

What is the state of Delaware’s liability, if any, for unlawfully evicting a man who is blind and his two school-age daughters during a snowstorm while executing an order to remove the previous tenant?

What extra steps should armed court constables have taken — such as providing the eviction order for the previous tenant in braille — so William Murphy could have made a better argument that he and his girls were not supposed to be cast out of their tiny rowhouse in the Southbridge section of Wilmington?

Those key questions are the focus of a lawsuit filed by the Murphy family in March 2021, one month after the trio was sent to the curb during a period when the state had put a moratorium on evictions because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Before being left outside on the cold, sleeting morning about four-and-a-half years ago, the Murphys were permitted to grab warm clothes but had to leave behind the girls’ school laptops, clothes, furniture and one precious item — an urn with Murphy’s late wife Lakia’s ashes.

“It was just one of the worst feelings when you feel like you failed as a parent and you know it’s not because of you,’’ Murphy recalled last week during an interview with WHYY News. “I never thought I could live in some place and be homeless within five to 10 minutes. It didn’t make any sense to me.”

The Murphys’ lawsuit claims that landlord Kenneth Stanford, the state Justice of the Peace Court and its three constables violated their constitutional rights to due process and legal protection against discrimination based on the disability of William Murphy, who lost one eye after a childhood attack and has severe glaucoma in the other eye.

Stanford, who is also a minister with Wilmington’s Bethel AME Church, later settled with the family. But last year Delaware’s chief federal judge, Colm F. Connolly, tossed the Murphys’ case against the court system and constables.

In essence, Connolly ruled that Murphy didn’t provide any facts that established he was evicted because of his disability. The judge also wrote that the lawsuit’s allegations “make clear” the eviction occurred because of Stanford’s “abuse of the law” — not because the state and its constables deprived Murphy of his constitutional right to due process and legal protection against discrimination because of his disability.

But this month, the Philadelphia-based U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit vacated the dismissal and sent the case back to his courtroom in Wilmington.

Rejecting Connolly’s conclusions in a 2-1 split decision, the appeals court panel noted that federal law required the constables to “make reasonable modifications” to their usual practices, such as holding off and getting the eviction order redone in braille or another form that allowed Murphy to grasp its full contents.

Murphy said he’s “elated” that his case against the state and constables has been revived.

“I’m happy that they decided to do that for me because my only real thought in the whole thing is that I feel like nobody listened to me,” Murphy said. “Nobody gave me a chance and nobody was understanding what I was trying to present to them and it was almost like, ‘Who cares?’”

Eviction order was for previous tenant, not the Murphys

The eviction order was for Viola Wilson, who had previously occupied the home, but Murphy had been renting it for about three months. He showed his signed lease to the constables, to no avail.

“I asked them a couple of times whose name is on the [eviction] paper that they had and they didn’t say me,” Murphy recalled. “They were saying a lady that used to live there and I’m telling them, ‘Well, I don’t know the lady.’”

The constables did call a supervisor from the snowy scene on Townsend Street, and were told to move ahead with the eviction “despite the deficient notice,” the appeals court ruled.

“The Murphys have plausibly pleaded that Murphy’s blindness led the defendants to evict them without notice readable by a blind person,’’ the ruling continued. “The constables gave Murphy written notice of the eviction that Murphy could not read because of his blindness. Despite knowing this, the constables evicted the Murphys anyway.”

State Deputy Chief Magistrate Sean McCormick had ruled soon after the eviction that “clearly the Murphys were unlawfully ousted.”

McCormick also wrote that landlord Stanford unlawfully “weaponized” the process to get an order to remove Wilson, who had moved out months earlier, in an unlawful attempt to force Murphy from the home.

Murphy had previously owed $375 in overdue rent, but that debt had been paid by the time constables knocked on his door while he was cooking pancakes for his daughters as his fifth grader and 10th grader were engaged in remote learning on Zoom.

“It became very clear that Stanford had at best misrepresented himself to the court; at worst, it was possible that he had perjured himself,” McCormick said during a hearing.

McCormick later referred the matter to state prosecutors for a criminal investigation, but no charges were filed against Stanford.

‘Notice still has to be in a form the blind man can read’

Stephen Neuberger, one of Murphy’s attorneys, rejoiced at the appeals court’s ruling and repeated the lawsuit’s claim that the state has an “evict first, ask questions later” policy that led to what all parties agree was the wrongful removal of the Murphys.

Neuberger said the ruling demonstrates that the state and its agents don’t have broad immunity for violating someone’s due process rights, which are guaranteed by the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, or for breaking federal law that protects people with disabilities.

“Even if you’re evicting the wrong person, the notice still has to be in a form that the blind man can read and understand,” Neuberger told WHYY News. “That’s the importance of the Americans With Disabilities Act and the importance of this ruling.”

The state can either appeal the ruling or let the lawsuit case return to Delaware’s U.S. District Court, where attorneys for the state Department of Justice would have to respond to the lengthy complaint’s assertions. What would follow are the production of discovery materials, depositions and perhaps a trial before a jury.

“We get to get into what happened behind the scenes in the state court system,” said Neuberger, who added that the Murphys want punitive and compensatory damages and an apology.

The state is still weighing its options, Chief Magistrate Alan Davis told WHYY News by text message.

“Unfortunately, I can’t comment on pending litigation,’’ Davis wrote. “We will be reviewing with the DOJ for next steps.”

Beyond returning to federal court, the Murphys’ lawyers are also taking the matter to Washington, D.C.

Neuberger said they will ask the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice “to investigate the entire Delaware magistrate court system and force it to comply with federal civil rights law in order to protect the rights of the poor and disabled.”

Murphy, who is now 57 and walks with a cane, said his lawyers helped him retrieve the family’s belongings, including his wife’s ashes, a couple of weeks after the eviction.

Shortly afterward, the Murphys moved to southern New Jersey, where William has been working with a manufacturing company that employs blind people. His younger daughter, Kayla, is now 16 and in 10th grade. Aaliyah, now 21, just completed cosmetology school.

Murphy says his daughters have moved past the humiliating experience.

“There’s no past remnants of anything that really traumatized them,’’ he said. “If you ask them about it, they’ll remember it and they’ll probably get five, 10 minutes of sadness.

“But I try to just turn it around. I’m not Jesus or nothing, but I try to make wine out of water for them.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.