‘Sublime’ folk sculptures by William Edmondson at the Barnes Foundation

Eight decades after his landmark exhibition at MOMA, William Edmondson’s “Monumental Vision” gets refreshed at the Barnes.

Listen 1:17

"William Edmondson: A Monumental Vision" is on view in the Roberts Gallery at the Barnes Foundation. Co-curator James Claiborne wants to disrupt the received notion that William Edmondson was a "naive" or "primitive" folk artist. (Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

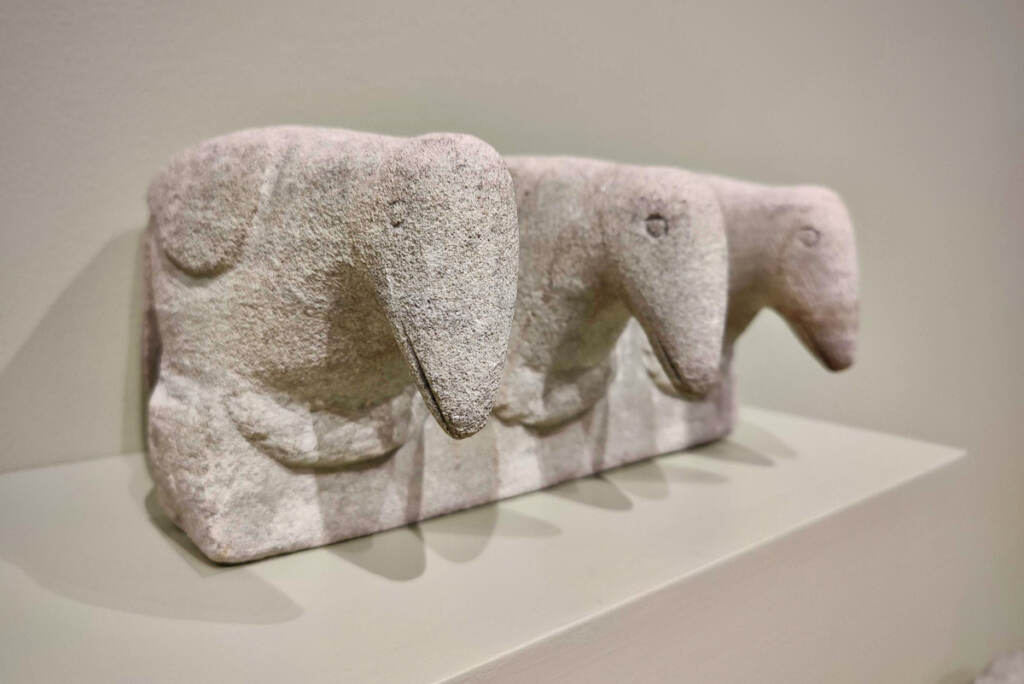

For its presentation of sculptures by the seminal Black American folk artist William Edmondson, the Barnes Foundation has strewn more than 60 carved limestone animals, people, and religious figures around its gallery space with little concern for chronology or theme.

This is how the curators believe the artist may have liked to arrange his sculptures in his yard in Nashville, Tennessee, according to a few existing photographs from the 1930s by Louise Dahl-Wolf and Edward Winston, on view in the exhibition.

Co-curator James Claiborne called it a “sublime space.”

“It is sublime to me,” he said. “It brings tranquility and contemplation, and a lot of joy.”

“William Edmondson: A Monumental Vision,” created by the Barnes Foundation, is the first major exhibition of Edmondson’s work on the East Coast in decades. It tries to reassess and untangle the legacy of the beloved artist.

During the Great Depression, Edmondson lost his job after working for more than 25 years as a hospital janitor. Needing work, he learned to carve stone and started making a living cutting gravestones for the segregated Black cemeteries of Nashville. He was almost 60 years old at the time.

Without any formal art education, he developed a distinctive carving style and started making sculptural pieces. Edmondson said he was instructed by a religious vision that came directly from Jesus, calling his figures “miracles.”

Although largely unknown outside of Nashville, in 1937 the Museum of Modern Art in New York City put Edmondson’s work on display. It was MOMA’s first solo show ever by a Black artist, and has become the defining fact of Edmondson’s artistic legacy. He died in 1951.

In its press materials at the time of the exhibition, MOMA portrayed Edmondson as “simple, almost illiterate, entirely unspoiled” who likely had “never seen a piece of sculpture not his own.”

In reality, Edmonson was a fairly successful artist and savvy networker who had a base of collectors in Nashville, and owned his own home — along with that sublime yard — at a time when home ownership was rare for Black Americans.

“The questioning of Edmondson’s faith, the positioning of him as a modern primitive, as someone uneducated — these framings around Edmondson have been pervasive,” Claiborne said. “What we hope to do is to disrupt that.”

The image of the “modern primitive” may have been goaded on by Edmondson, himself, who likely was aware of how the largely white, affluent art community in New York wanted to perceive him.

Press at the time quoted him using a phonetic patois, such as: “Dis here stone n’ all those cut there in de yard – come from God. It’s de word in Jesus speakin’ his mind in my mind,” according to Charlotte Barat and Darby English in their essay “Blackness at MOMA: a Legacy of Deficit.”

“It’s likely that Edmondson played a little with the journalists who were interested in him,” said Barnes co-curator Nancy Ireson. “He understood the stereotypes that were brought to readings of his work. A lot of what he said was tongue in cheek. So it is tricky trying to piece together a real sense of who Edmondson was as a person.”

The original creator of the Barnes Foundation, Albert Barnes, would have likely known about Edmondson and the MOMA exhibition, but did not collect any of his works. “A Monumental Vision” is composed entirely of loaned pieces from museum and private collections, including the popular artist and designer KAWS, who owns many Edmondson works.

The exhibition at the Barnes explores Edmondson’s deeply reverent religious instincts and how they dovetailed with other aspects of his life, in particular the Black community of Nashville. For example he repeatedly carved a figure of two women sitting side by side, sometimes labeling them as “Martha and Mary,” two Biblical figures who encounter Jesus in the Gospel of Luke.

Other times nearly identical figures could be titled “Po’ch Ladies,” something he would have seen commonly on the porches of Nashville’s Black neighborhoods. The exhibition features yet another variation of the pair, set within an Ancient Egyptian motif.

“Sometimes you’ll see something very literal, like he’ll carve a lovely little squirrel — he’s just sort of holding a nut in its hand,” Ireson said. “And then sometimes there are these incredible leaps of imagination. He makes a carved mermaid who has an almost Egyptian profile.”

“Lots of different nuances and contradictions within the artist makes him all the more fascinating,” she said.

“A Monumental Vision” will feature an interpretive performance element: On Saturdays from July 15 to September 2, dancers will enter the gallery space and perform a choreography by Brendan Fernandes among the sculptures. It is the first time the Barnes will stage dance performances inside one of its exhibition galleries.

Claiborne hopes Fernandes’ dance and visual art installation draws a wider range of people to consider Edmondson.

“I think there’s something compelling about introducing Edmondson to a Kenyan-born, Canadian, queer visual artist and asking him to join us in the interpretation,” Claiborne said. “It will allow a more diverse, more nuanced audience to consider the ways that these sculptures carved in the 1930s have something to say to them.”

“William Edmondson: A Monumental Vision” will be on view until Sept. 10.

Show your support for local public media

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.