Why Philly keeps a billion-dollar open-air drug market contained in Kensington

The containment of Kensington’s drug market demonstrates the systematic racism that plagues Philadelphia, Eduardo Esquivel writes.

Eduardo Esquivel at McPherson Square Park in Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood on Aug. 24, 2021. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Every morning I wake up, open the curtains of my bedroom, and prepare myself for the possibility of witnessing another free samples line on our small Philadelphia street.

Here on the block where I live with my wife, drug dealers herd people deep in the throes of addiction like cattle toward the promise of a small amount of free drugs, in hopes that they’ll come back for more. They gather 50 people or more at a time. Sometimes people fight, driven by withdrawal, trauma, and the powerful effects of the drugs themselves. The whole event can appear in minutes. I have recurring nightmares about the times these lines have grown even more out of control, with people punching and kicking each other, falling into cars and houses, neighbors trapped and terrified.

As a social worker, I was surprised when my wife and I moved to our current home several years ago that there was no neighborhood association in place in our area, something we saw as necessary to check the kind of destructive development that had already swept through many parts of Kensington and Fishtown. I’ve been in Kensington for 11 years, so I know the cycle and knew our area was next.

It has become incredibly clear since then why no such organization has survived in the area we represent: This city and region have maintained a decades-long strategy of containing a billion-dollar drug market in my neighborhood, and that strategy has obliterated any attempts to organize.

The laws that govern drug sales, use, and acceptable behaviors on streets, in park spaces, and even on private property in the rest of Philadelphia very purposefully do not apply here, and what such a wholesale suspension of norms and protections can do to a poor, majority Black and brown community is on full display. The impact of this dangerous and racist strategy is why I now spend my time advocating for my community as the president of Kensington Neighborhood Association.

People struggling with addiction stream into our community from within the city and from outside of it. They buy drugs, often using them in their cars before driving impaired through our narrow streets where our young children play. Sometimes these drivers lose consciousness behind the wheel.

Without the backyards of less dense areas, our children have few safe places to play. The city operates neighborhood parks, yet the needles that carpet the grass, along with human waste and the presence of people intoxicated on opioids, cocaine, methamphetamine, and K2, make these places risky to go.

I have watched block after block become impassable without meeting the discerning eye of young men lured into a pyramid scheme of drug dealing, chasing riches that won’t appear and using threats of violence to stake out their territory against dealers and residents alike. I have spoken with social service providers who cannot park near these blocks anymore to assist their clients, having been told by these same dealers that their presence is a threat — the boss says they look like police.

Many people will talk about I-95, the presence of the El stops in the neighborhood, and the past abundance of abandoned factories and homes as the natural causes of Kensington becoming the site of more than 50 separate open-air drug markets at a time, with people spending hundreds of millions of dollars here per year. But it’s not as if Kensington is home to rolling fields of poppies being processed into heroin, and any attempts to find natural causes is doomed to failure — plenty of other neighborhoods near transit and highway stops have struggled with abandoned properties without also containing the largest open-air drug market on the East Coast. The market is here because it is highly convenient for so many to contain the problem here, far away from affluent, white areas whose residents have historically driven in to buy drugs, use them, and leave. And my Black and brown neighbors have been told, both implicitly and explicitly, that the accompanying violence and community destruction inherent in open-air drug markets is their burden to bear, and that the wellbeing of themselves and their families simply don’t matter.

Let’s be clear: The highly successful containment effort in Kensington is systemic racism in action. Those with the power to reinforce this system, including powerful governmental actors, wealthy power brokers, and everyday individuals making seemingly innocuous and small decisions, have used many tools over the years to contain these destructive markets in Kensington, including one dating back to the 1980s using targeted policing that sanctioned sales and use within Kensington — while cracking down heavily on them around its borders, ensuring that the dealing did not spread to other neighborhoods. Police have acknowledged this history in private meetings, but it’s never been officially recognized.

Another tool has been a version of NIMBYism that, intentionally or not, has worked in an almost coordinated manner across neighborhoods and nearby counties. These surrounding areas outside of the city have a long and well-documented history of using zoning and other techniques to keep out affordable housing, shelters, drug treatment, and locations for distributing related medical supplies.

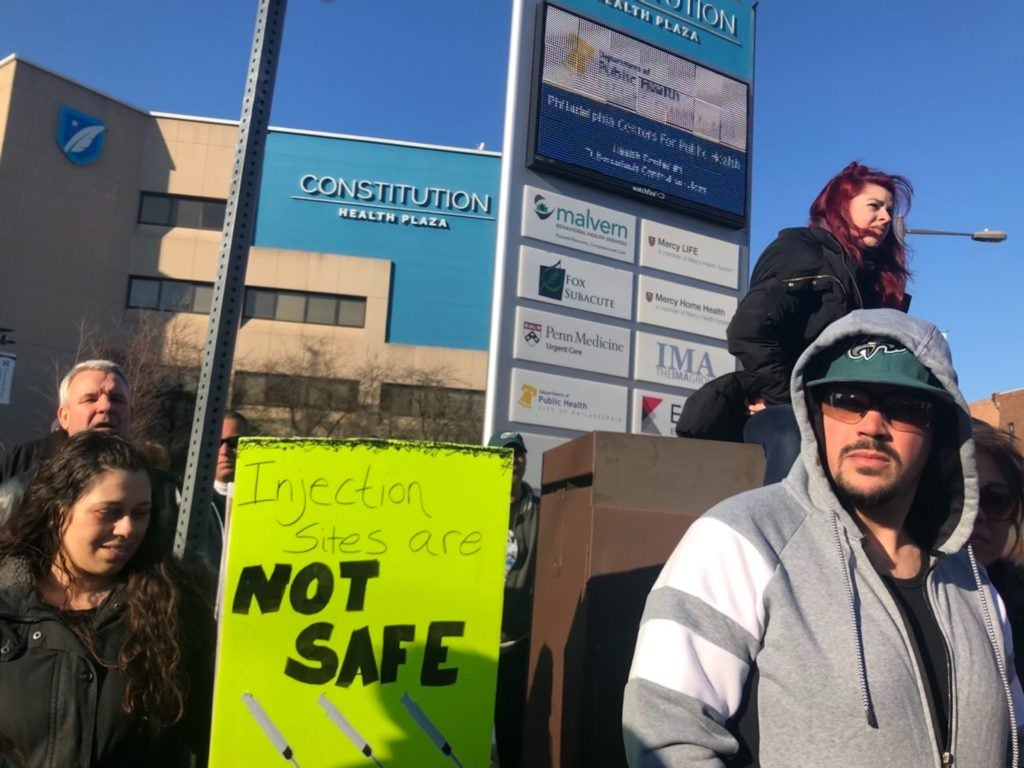

When any efforts have been made to place infrastructure for those struggling with addiction in other areas, those pushing NIMBY policies spring into action. The rapid meltdown of a plan to place an overdose prevention site in South Philadelphia reveals how quickly neighborhoods will respond, though one must wonder how dedicated the city was to placing anything there if it didn’t even bother to have conversations with these neighbors ahead of time.

Another prominent example is the distribution of syringe disposal cans. I sat in meetings with city officials when they proposed these as a solution to the proliferation of needles all over our neighborhood. They did not explore expanding needle exchange programs throughout the city to stop concentration within the neighborhood or announce partnerships with outside counties to meet the needs of those using injection drugs near their homes. They put these bins at each El stop in Kensington and one in McPherson Square and declared it a success.

The message was clear: You can use injection drugs outside, but only in Kensington. No wonder our SEPTA stops became overrun with drug use so rampant they shut down temporarily earlier this year. No wonder McPherson Square Park has essentially become a sanctioned shooting gallery and nearby E, F, and G streets have been packed with different drug crews.

This very successful strategy becomes self-reinforcing. Over time, as more and more burden is placed on the community, the community itself becomes seen as synonymous with the problem, a neighborhood-level version of blaming the victim. Where Kensington started as the place to contain the problem of drug use for a whole region, it is reinforced by blaming residents for the very problems heaped upon them. As the message is firmly reinforced, even the name of the neighborhood is lost. It’s no longer Kensington, but instead “The Badlands.” McPherson Square Park (and before it Norris Square Park) becomes “Needle Park,” a codification that only further reinforces the imposed decision that Kensington is where the region has offloaded its drug-related issues.

This all leads to the development of the implicit assumption that those living in Kensington are either addicted to or selling drugs — if they’re there, they must deserve it. As this narrative is cemented by both active and self-reinforcing means, it has filtered down as an unquestionable truism that has poisoned neighborhood interactions.

I remember talking to people struggling with addiction about basic norms for public use that were mutually respectful, allowing neighbors and those using to maintain an uneasy equilibrium. People were asked not to use in front of families or in front of children, and were largely understanding, if forgetful, as they struggled with powerful drugs and years of trauma. Increasingly, as people are reassured constantly of our community’s worthlessness as anything but a drug market, we have heard a familiar phrase in response to neighbors’ pleas: “This is fucking Kensington.” “Why don’t you just move?”

I’ve heard from multiple young mothers who, in asking people not to use in front of their children, were shamed for the perceived sin of raising children in the neighborhood at all. To quote another person, who had just urinated in front of our neighbor’s children in broad daylight before proceeding to purchase drugs, “This ain’t motherfuckin’ Beverly Hills.” Perhaps most salient was a man who was so driven by this imposed ideology that he attacked me just 50 feet from my home as I told him it was not OK to inject himself in the neck in front of a house full of children.

What’s to be done? Provide housing for those experiencing homelessness, provide quality treatment for those who so desperately need it and eliminate the myriad barriers that still exist so prominently in the system, and provide our neighbors and those struggling with addiction with the same basic public safety and sanitation systems that are enjoyed by the city’s affluent white residents. What we can’t do is continue to dump the weight of this city-wide and regional drug epidemic on my neighborhood and by extension, on my Black and brown neighbors.

The containment of this problem in Kensington demonstrates the systematic racism that plagues our city, and we must reject any argument to preserve this racist status quo.

Eduardo Esquivel is the president of Kensington Neighborhood Association and a social worker who has lived and worked in Kensington since 2010. During this time he has worked at multiple non-profits with those experiencing chronic homelessness and struggling with mental health and substance abuse.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.