Why do majority-white city commissions pick the Philly history saved and celebrated?

The Philadelphia Historical Commission and Philadelphia Art Commission – are the legacy of systemic racism and racial exclusion.

An eager crowd surrounds the statue of Octavius Catto after its unveilling on the Southwest apron of City Hall. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Seven weeks ago, Mayor Jim Kenney announced his desire to remove the Christopher Columbus statue from South Philadelphia’s Marconi Plaza. The move came in response to violent protests against anyone who dared to challenge the controversial Italian explorer’s place in colonial history. In a tweet, Mayor Jim Kenney said, “Part of reckoning with the legacy of systemic racism means reconsidering what figures deserve to be commemorated in our public spaces.”

Part of reckoning with the legacy of systemic racism means reconsidering what figures deserve to be commemorated in our public spaces.

On July 22, the City will ask the Philadelphia Art Commission to approve the removal of the Christopher Columbus statue. https://t.co/pmX1CHrvqH

— Jim #MaskUpPHL Kenney (@PhillyMayor) June 24, 2020

But what happens when the institutions doing the reckoning – Philadelphia Historical Commission and Philadelphia Art Commission – are themselves the legacy of systemic racism and racial exclusion?

The demographics of Historical Commission members and staff look like guests at Le Dîner en Blanc. Two of the seven appointed commissioners are Black and the staff is 100% white. The demographic makeup of the ex officio commissioners is also mostly white with only one nonwhite person among the six — City Council President Darrell Clarke. Clarke is the only Black man in a decision-making capacity at the Historical Commission, though one ex officio commissioner who recently resigned is Black. The ex officios can operate with designees who attend meetings and vote. Three of the designees are white while two are Black and one is Latinx, according to a spokesperson for the city.

The Art Commission, too, skews white. In the year 2020, the body that gets the final deciding vote on public art in Philadelphia has only one Black member. Out of nine total members, the commission has three Latino members, one from Puerto Rico and two from Venezuela. The remaining five members are white. As with the Historical Commission, Black men need not apply.

The Commission recently made headlines as the city body that must approve Kenney’s proposal to remove the Columbus statue. The Art Commission will vote August 12, following a vote by the Historical Commission in favor of the removal.

Established in 1907, the Art Jury is the predecessor of the Art Commission. The demographic makeup of the Art Commission is little changed from the Jim Crow era. The Commission touts that its mission “is much the same as when it was founded.” That’s hardly reassuring given the Art Jury consigned the All Wars Memorial to Colored Soldiers and Sailors to the back of the bus in 1934 and the Commission, in 1998, approved placement of the Frank Rizzo monument in Thomas Paine Plaza — a decision overruled after years of protest from Black activists who finally could no longer be ignored this summer.

The Art Jury blocked the location of the All Wars Memorial on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. The memorial was hidden away in West Fairmount Park for 60 years. In a recent story, the Association for Public Art observed: “The history of this memorial and the racism that lies at the heart of its long journey should be revisited at this time, when we strive toward racial justice and reflect on monuments across the nation.”

According to the Smithsonian Institution Research Information System, Philadelphia has more than 700 works of art in its portfolio. It is telling that the first monument to a sole African American on city-owned property was installed in 2017 – 65 years after the Art Commission was founded. A quest for parity, the Octavius V. Catto Memorial was commissioned and funded by a private nonprofit organization, the Octavius V. Catto Memorial Fund.

The built environment reflects racial inequities. The decision about whether a monument should stand or a historic property be protected is inevitably a social justice issue. Historic preservation is about more than ornamental brick-and-mortar. It’s also about storytelling. The question then becomes: Whose story is preserved in public memory?

At the Historical Commission, the white gaze is the default standard for historical or cultural significance. Implicit bias led to the spectacle of commissioners overruling the unanimous vote of the Committee on Historic Designation and denying protection to the Henry Minton House, one of the last places where John Brown laid his head before the Harpers Ferry Raid. While acknowledging the property meets the statutory criteria for designation, the Commission ruled the façade is not “recognizable” because of an 1894 renovation that concealed the original building.

But while the 204 S. 12th Street former Minton home didn’t meet the commission’s subjective standards, the site irrefutably contained memories important to the city’s Black history.

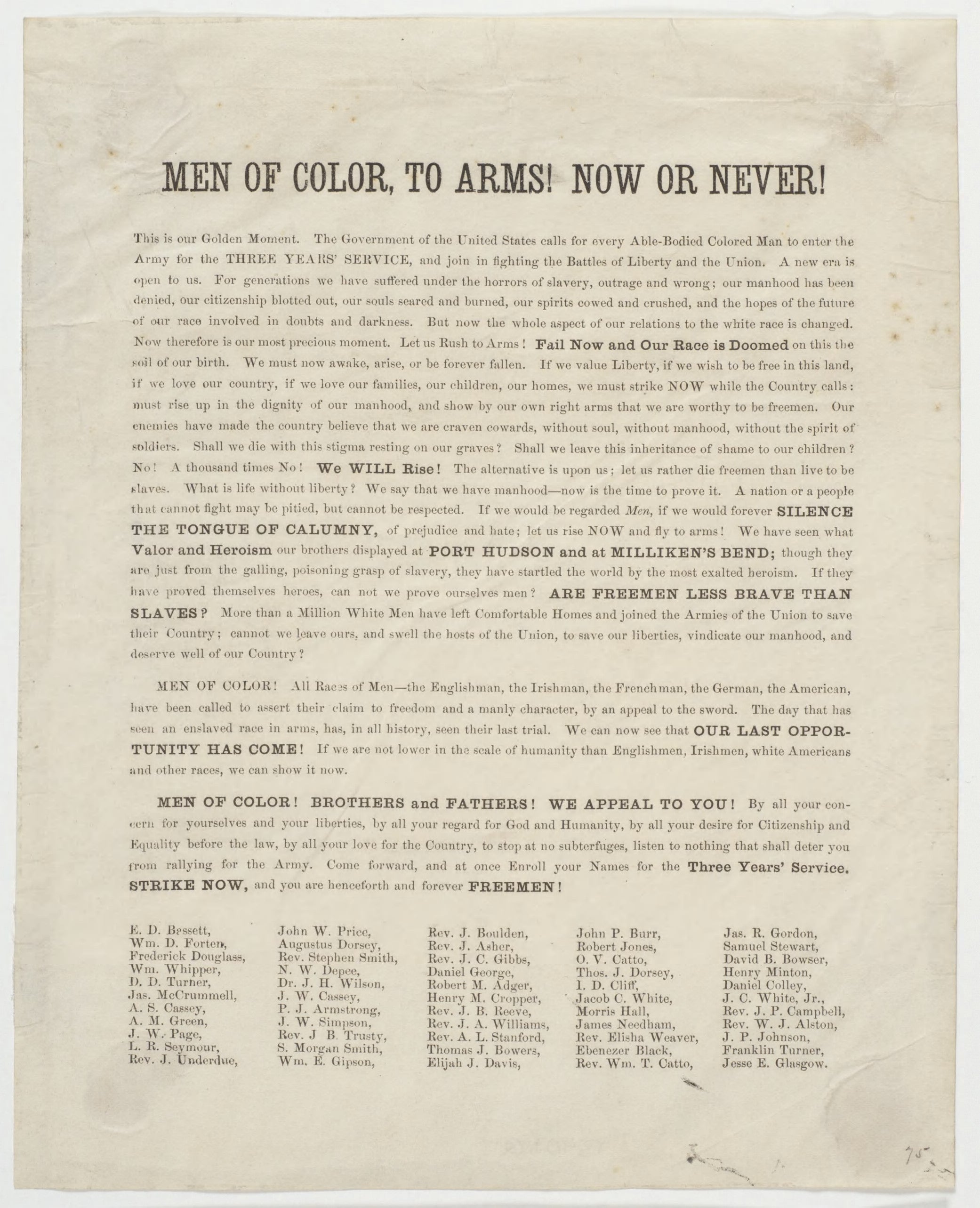

In The Philadelphia Negro, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote that Minton “wielded great personal influence, aided the Abolition cause to no little degree, and made Philadelphia noted for its cultivated and well-to-do Negro citizens.” Minton was one of the cosigners of an iconic Civil War recruitment broadside.

A building whose walls hold stories of the Underground Railroad and Frederick Douglass was denied protection from demolition based on a standard – “recognizable” – that does not exist in the historic preservation ordinance.

It’s a pattern that plays out regularly at the Historical Commission, says Oscar Beisert, a co-founder of The Keeping Society of Philadelphia. Beisert has submitted nearly 100 nominations, including the Henry Minton House in 2019.

“Unlike the plan that restored hundreds of buildings related to 1776, there is no effort to preserve and protect Black history in Philadelphia,” Beisert said. “While many recreated and restored façades of the 18th century are rightfully protected, they represent white history, and Black sites are treated differently, especially when wealthy developers are involved.”

Beisert describes the Commission’s approach as a form of architectural Jim Crow.

Black historic sites must “pass a more stringent literacy test called architectural integrity before being protected,” he said.

As of this month, the owner of the Minton house is moving forward with plans to demolish it to make way for a glassy condo tower — renderings show a building similar to many others sprouting across the city.

“If only George Washington had stayed the night, the façade would be a non-issue and we could protect this rare surviving Black landmark,” Beisert said.

WURD talk show host Charles Ellison debunked the notion that institutions can credibly address the legacy of systemic racism without including African Americans in the conversation.

open note to all private and public sector institutions: stop thinking you can do any equity, diversity, inclusion & disparity work and not hire or have Black professionals on staff – especially in leadership positions – doing that work. So, yeah, cut that out.

— cdellison (@ellisonreport) July 31, 2020

As public institutions — including the Philadelphia Police Department, School District of Philadelphia and The Free Library — confront racial injustice, the Historical Commission and Art Commission must face their own racial reckoning.

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.